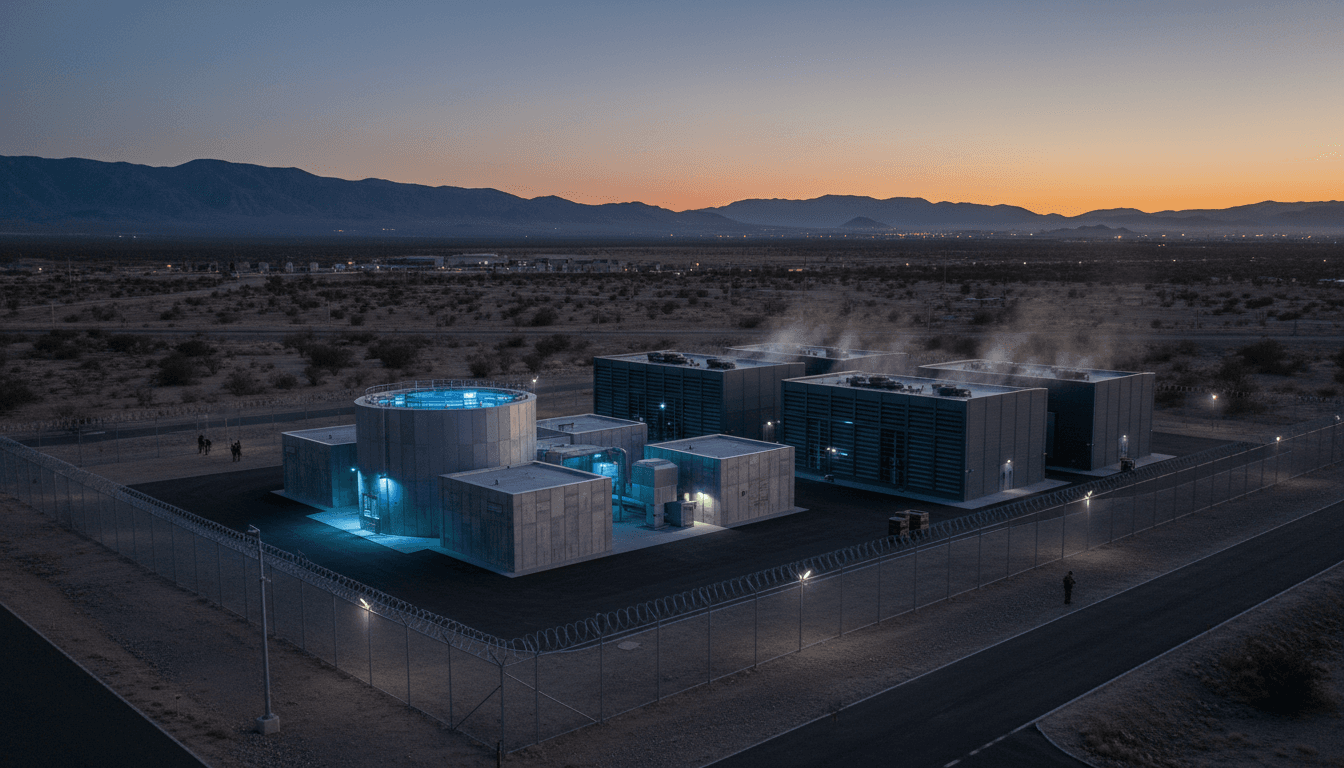

Army microreactors aim to make bases energy-independent by 2027—key for AI-ready defense infrastructure, resilience, and secure power operations.

Army Microreactors: Powering AI-Ready Bases by 2027

A modern military base can lose electricity for 60 seconds and shrug it off. Lose power for 60 minutes, and you start seeing cascading failures: communications degrade, fuel pumps stop, security systems go to fallback modes, and the “digital backbone” that makes everything else work begins to fray.

That’s why the Army’s goal to break ground on a microreactor at a U.S. base by 2027 deserves attention beyond the energy community. It’s not just a story about nuclear power. It’s a story about whether the Department of Defense can build AI-ready infrastructure—the kind that supports autonomy, cyber defense, sensing, and mission planning without being held hostage by a fragile grid or a never-ending diesel logistics tail.

The Army’s newly announced Janus Program aims to bring advanced nuclear designs into real-world use at installations, with officials indicating a reactor could go critical as early as July 2026 and construction starting the following year. The promise is straightforward: energy independence for bases. The hard part is everything underneath that promise—fuel supply, safety, licensing, ownership models, and how you operate a nuclear asset inside a highly networked environment.

Why microreactors are showing up in the AI basing conversation

Microreactors matter because AI systems turn electricity into operational advantage. When defense leaders talk about “AI in defense & national security,” they’re often talking about models, sensors, data pipelines, and decision support tools. Those don’t run on good intentions; they run on power, cooling, and uptime.

Here’s the practical connection: as bases deploy more AI-enabled ISR, autonomous system maintenance, cyber analytics, and real-time mission planning, their load profile starts looking less like an office park and more like a small industrial campus.

AI doesn’t just need power—it needs reliable power

A base can’t plan for AI workloads the way a commercial enterprise does (burst to cloud, fail over to another region, delay noncritical training jobs). Defense operations often require:

- Deterministic availability for command-and-control and base defense systems

- High quality power (stable frequency/voltage) for sensitive compute and comms

- Resilience under disruption, including regional grid failure or cyber incidents

- On-base generation that reduces dependence on fuel convoys and third-party utilities

Microreactors fit that shape: long-duration generation, small footprint relative to traditional nuclear plants, and the potential to run for extended periods with minimal refueling.

Energy resilience is becoming a warfighting enabler

Most companies get this wrong: they treat energy as a facilities issue. For national security, energy is a mission dependency.

When the Army talks about bases operating if the wider grid goes down, that’s not theoretical. Grid fragility is driven by extreme weather, aging infrastructure, and increasingly capable cyber threats. If you’re building an “AI-forward” base—one that uses automation to accelerate decisions and tighten defensive loops—you can’t build it on top of unreliable power.

What the Army actually announced—and why the timeline is aggressive

The Janus Program is a joint Army–Department of Energy push to accelerate microreactor deployment on installations. Army and DOE leadership announced it at the Association of the U.S. Army conference, and the Army’s senior installations leadership indicated construction likely won’t begin until 2027, even if a prototype goes critical in 2026.

That sequencing matters:

- “Go critical” is a technical milestone (the reactor achieves a sustained nuclear chain reaction).

- “Break ground on a base” is an infrastructure, regulatory, contracting, and community milestone.

Those two are related, but they’re not the same problem.

The contracting model signals a shift toward speed and accountability

The Army plans to use a milestone-based contracting approach through the Defense Innovation Unit, with reactors commercially owned and operated. That’s a big deal.

It suggests the Army wants:

- Faster iteration than traditional procurement

- Clear go/no-go gates tied to performance

- A structure that pushes some execution risk to industry

The model is reportedly inspired by past “commercial partnership” approaches used in other domains, which is a polite way of saying: the Army wants the innovation tempo of the private sector, but with defense-grade requirements.

There are no operating microreactors in the U.S. today

The Army is trying to compress timelines in a space where the U.S. has zero currently operating microreactors. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible—it means there’s little operational precedent.

If you’re responsible for base modernization, this is the key takeaway: the schedule risk is real, and it’s not only about reactor physics. It’s about licensing pathways, site prep, interconnection, emergency planning, workforce readiness, and supply chains.

The hard problems: fuel, safety, and “this becomes a target” fears

Microreactors will succeed or fail on fuel availability and operational trust. The Army can announce timelines; the ecosystem has to deliver the boring but decisive pieces.

Fuel supply is the constraint that keeps showing up

U.S. nuclear fuel supply chains—especially for advanced reactor concepts—face constraints tied to enrichment capacity and sourcing. That’s not a niche detail. It’s central to whether microreactors can scale beyond pilots.

From a national security perspective, fuel dependence creates a strategic vulnerability: if your “energy independence” plan relies on externally constrained fuel, you’ve moved the chokepoint, not eliminated it.

What to watch through 2026–2028:

- Whether domestic enrichment and fabrication ramp to predictable timelines

- Whether reactor vendors lock in long-term fuel contracts early

- Whether DoD treats fuel as a strategic enabler (not an afterthought)

Safety and community acceptance aren’t optional

Even if a microreactor is designed with modern passive safety features, the acceptance equation is broader than engineering. Installations sit near communities. They rely on local emergency response ecosystems. They live under political scrutiny.

If you’re planning for AI-ready installations, here’s what works in practice:

- Pre-brief local stakeholders before rumors become the story

- Treat emergency planning as a co-designed effort (base + local + state)

- Invest in transparent monitoring that’s understandable to non-experts

Trust is operational. Without it, projects stall.

“Attractive target” concerns need a clearer answer than reassurance

Some analysts argue microreactors could become attractive targets. The Army’s stance is that these systems are on U.S. soil, not deployed forward, and contain small amounts of fissile material relative to larger systems.

That’s a start, but I’d push for a more operationally grounded framing:

A microreactor on a base isn’t primarily a nuclear safety problem—it’s a physical security plus cyber-physical assurance problem.

If adversaries can’t easily cause radiological release, they may still aim for disruption: shutting it down, confusing operators, triggering false alarms, or forcing a safety scram at a critical time.

Which leads directly to AI.

Where AI fits: from energy security analytics to autonomous operations

AI will be part of the microreactor story whether the Army plans for it or not. The question is whether AI is used as an afterthought (“add a dashboard later”) or as a design requirement.

AI can reduce downtime—but only if the data architecture is built first

Microreactors and the surrounding plant systems generate rich operational data: temperatures, flows, vibration signatures, valve states, generator performance, switchgear health.

Applied correctly, AI helps with:

- Predictive maintenance (detect failures before they trip)

- Anomaly detection (spot unusual patterns that indicate faults or tampering)

- Load forecasting (match generation and storage to mission demand)

- Fuel and lifecycle optimization (maximize availability while staying within constraints)

But here’s the catch: you can’t “AI your way” out of bad instrumentation and messy data. If the plant’s operational technology (OT) data isn’t standardized, time-synced, and governed, AI outputs will be noisy—and in a nuclear-adjacent environment, “noisy” becomes “unusable.”

Cybersecurity is the make-or-break layer for AI-enabled power

An AI-enabled energy system increases the importance of defending:

- OT networks (control systems, sensors, protection relays)

- IT networks (analytics platforms, identity, patching)

- The boundary between them (where attackers love to live)

For defense installations, the right stance is blunt: assume the microreactor ecosystem will be probed. That includes vendors, remote support channels, update mechanisms, and third-party monitoring.

Practical controls that should be treated as baseline:

- Strong segmentation between OT and enterprise IT

- Hardware-backed identity for devices and operators

- Strict change control and signed updates

- Continuous monitoring tuned for OT protocols

- Regular “tabletop to live” exercises that include grid-loss scenarios

Microreactors can stabilize the base compute stack

AI workloads are spiky. Training runs, simulation, sensor ingestion, and cyber analytics can surge.

A microreactor won’t eliminate the need for batteries, generators, or demand management—but it can provide a steady baseload that makes those other systems more effective. Think of it as changing the base from “always catching up” to “operating from a stable floor.”

What success looks like by 2027–2028 (and how to measure it)

A microreactor program is successful when it improves mission assurance with measurable uptime and manageable risk. Not when it produces a nice rendering.

Here are concrete metrics defense leaders should demand:

Operational performance metrics

- Availability (% uptime) over a rolling 12-month window

- Mean time to recover after forced outages or safety scrams

- Power quality performance (frequency/voltage stability)

- Islanding performance (how cleanly the base separates from the grid)

Security and resilience metrics

- Time to detect OT anomalies (minutes, not days)

- Number of unauthorized changes prevented (and how)

- Incident response drill outcomes (measured, not anecdotal)

AI-readiness metrics

- Percentage of plant assets instrumented for predictive maintenance

- Data latency and time synchronization accuracy

- Percentage of maintenance tasks shifted from reactive to planned

If the Army can show these numbers improving, the program becomes more than a demonstration—it becomes a template.

What this means for the “AI in Defense & National Security” roadmap

AI adoption in national security is increasingly gated by infrastructure, not algorithms. The Pentagon can buy software faster than it can build resilient power and network foundations. That mismatch creates a predictable outcome: impressive pilots that can’t scale.

Microreactors are one attempt to close that gap—especially as AI capabilities increase base power demand and raise the cost of downtime. If the Army can execute Janus with disciplined contracting, transparent safety practices, and a fuel strategy that scales, it sets a precedent other services will follow.

If you’re building programs at the intersection of AI and defense infrastructure, the near-term question isn’t “Will microreactors exist?” It’s this: Will we design the cyber, data, and operational layer so microreactors actually deliver mission assurance instead of becoming another brittle dependency?

If your team is evaluating AI for mission planning, cyber defense, or autonomous base operations, treat power resilience as a first-class requirement. The smartest model in the world is still just a server that needs electricity.