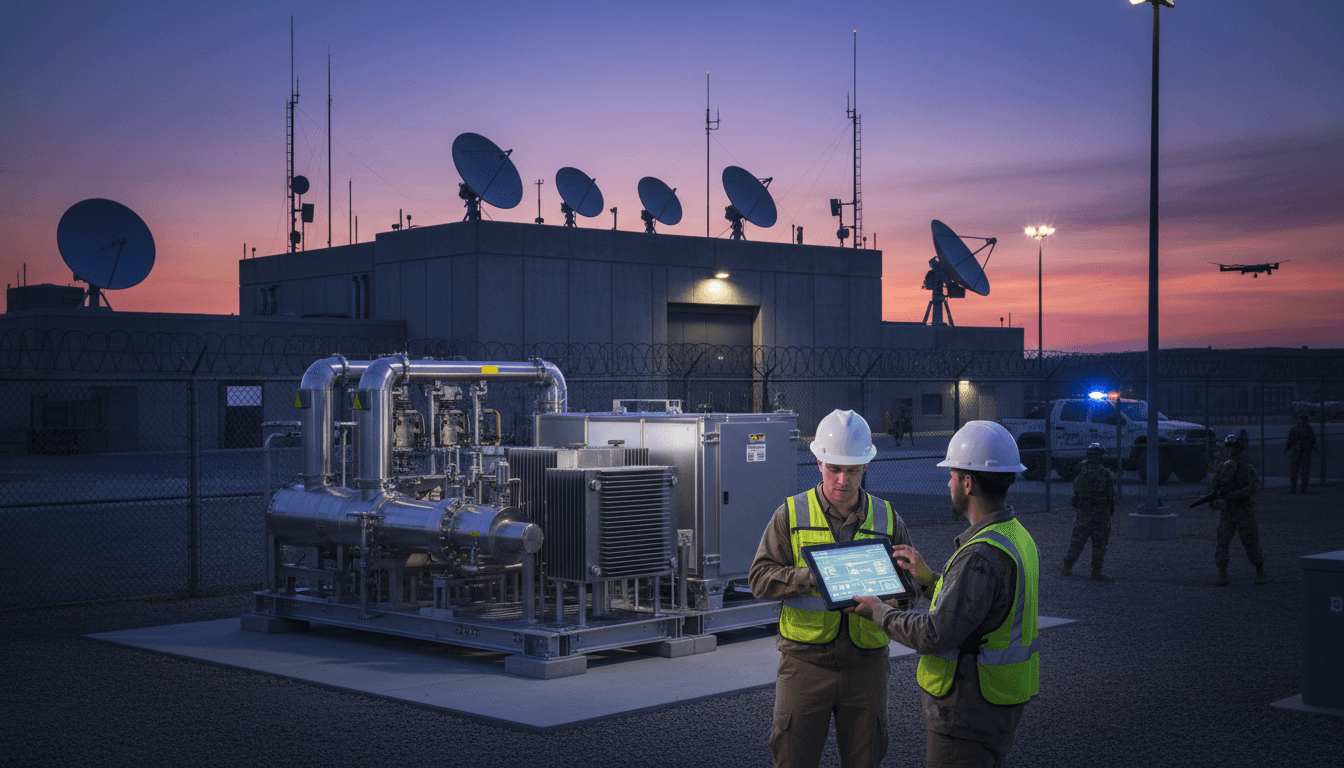

Army microreactors by 2027 shift energy security into mission assurance. Here’s how AI monitoring, microgrids, and OT cyber make them operationally viable.

Microreactors on Army Bases Need AI-First Ops

A single power outage can pause flight lines, break maintenance schedules, and force commanders into ugly tradeoffs—protect the mission systems or keep the lights on. That’s why the Army’s plan to break ground on a microreactor at a U.S. base by 2027 is bigger than an energy story. It’s an operational resilience story.

And it’s also an AI story.

Microreactors don’t succeed on ambition alone. They succeed when they’re operated like modern critical infrastructure: instrumented, monitored, defended, and optimized continuously. In the AI in Defense & National Security series, we usually talk about ISR, autonomy, and cyber. This time the target is different: the base itself. If installations are the “home port” for every mission, then energy security is national security, and AI-enabled energy management is becoming part of readiness.

Why the Army is chasing microreactors (and why now)

The direct answer: because diesel supply chains and fragile grids are operational liabilities. A base that can’t power communications, maintenance bays, water systems, and command-and-control during grid disruption is a base that can’t generate combat power.

The Army’s Janus Program aims to bring new reactor designs into real use—starting with a goal to see a small reactor go critical by July 2026, and then begin construction at a U.S. installation in 2027. That timeline is aggressive, but the logic behind it is straightforward:

- Grid reliability isn’t guaranteed. Severe weather, cyberattacks, and physical sabotage are now baseline planning assumptions.

- Diesel is costly and exposed. Fuel convoys, contracts, storage, and emissions controls create continuous operational friction.

- Compute demand is climbing. AI workloads, sensor fusion, and mission systems push bases toward higher and more stable electrical loads.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: microreactors are less about “new power” than they are about “assured power.” That shift matters for planners because assured power changes what you can safely centralize on-base—data, logistics automation, cyber defense stacks, even certain training simulators.

The “AI power problem” nobody wants to own

A lot of defense organizations want AI capabilities, but fewer want to fund the boring parts: power, cooling, and uptime. As AI adoption expands—especially at the tactical edge and across installations—energy becomes a limiting factor.

Microreactors are one answer. They’re not the only one (solar + storage, small modular reactors, hybrid microgrids, demand response), but they’re unique in one respect: they can provide steady baseload power for years without the daily logistics of fuel delivery.

The real work starts after construction: operating a microreactor safely at a base

The direct answer: operational success depends on instrumentation, safety culture, cyber-hardening, and a trained workforce. The reactor is the hardware; the operating model is the capability.

The RSS report highlights two persistent concerns that will shape execution:

- Safety and security risk perceptions (including the idea that reactors could become attractive targets)

- Fuel supply constraints (the U.S. enrichment pipeline isn’t fully where it needs to be)

Those concerns won’t be solved by messaging. They’ll be solved by a credible operating architecture—one that can prove safety, detect anomalies early, and maintain compliance while staying resilient against cyber and physical threats.

Safety isn’t a slide deck—it's telemetry plus procedure

For microreactors on U.S. bases, the bar is simple: the system must be demonstrably safe under normal operations and credible abnormal scenarios.

That means:

- Dense sensor coverage across thermal, vibration, radiation, coolant flow, and power conversion

- Continuous verification against operating envelopes

- Procedure automation that reduces operator workload without hiding critical context

- Routine drills that treat “weird signals” as incidents, not inconveniences

This is exactly where AI for real-time monitoring belongs—because humans are great at judgment, but terrible at staring at dashboards for thousands of hours and catching the one subtle pattern that matters.

Where AI fits: microreactor ops, microgrids, and mission assurance

The direct answer: AI adds value when it reduces unplanned downtime and improves decision speed—without compromising safety or control. It should support operators, not replace them.

Think of the microreactor as one node in a broader installation energy system that includes microgrids, storage, generators, and prioritized loads. AI can help at three layers:

1) AI for predictive maintenance (keep the reactor available)

The best way to avoid safety incidents is to avoid equipment degradation surprises.

A practical, defensible predictive maintenance stack for a microreactor environment typically includes:

- Anomaly detection on time-series data (temperature gradients, pump signatures, power conversion efficiency drift)

- Remaining useful life estimates for components that wear (valves, bearings, heat exchangers in the balance-of-plant)

- Maintenance scheduling optimization aligned to base ops tempo

The key metric to manage: forced outage rate. If microreactors are pitched as resilience infrastructure, they must be reliable enough to earn trust from commanders and installation managers.

2) AI for smart microgrid control (keep the base running)

A base doesn’t need “maximum power.” It needs the right power to the right loads at the right time.

AI-enabled microgrid energy management can:

- Forecast load using historical patterns (training cycles, weather, maintenance periods)

- Optimize dispatch across reactor output, batteries, and backup generation

- Automatically shed non-critical loads during anomalies while preserving mission systems

- Run “what-if” simulations for contingency plans

Snippet-worthy truth: Resilience is a control problem, not a generation problem. Microreactors help generation; AI helps control.

3) AI for cyber defense of operational technology (OT)

If you connect a reactor-adjacent control network to anything else, you inherit risk. Microreactor systems will require a hard separation of safety-critical controls from enterprise IT, but even “air-gapped” environments still face threats through maintenance laptops, supply chain vulnerabilities, and insider risk.

AI-driven OT security can contribute by:

- Baseline modeling of normal PLC/SCADA traffic patterns

- Detecting lateral movement and abnormal command sequences

- Identifying spoofed sensor data or “too-consistent” signals

Here’s the stance: microreactors without modern OT cyber monitoring are a self-inflicted readiness risk. The question isn’t whether attackers will try; it’s whether you’ll know quickly when something changes.

Contracting and commercialization: why the Army’s model matters

The direct answer: milestone-based contracting plus commercial ownership could speed adoption—if performance requirements are unambiguous.

The Janus approach uses a milestone model through the Defense Innovation Unit and keeps the reactors commercially owned and operated. That structure is doing two things:

- Encouraging vendors to build systems that can survive in a commercial market (not only a bespoke program)

- Making schedule and performance measurable through milestones instead of promises

This mirrors lessons learned from other “deliver capability, not paperwork” models.

But it also raises a practical question every base commander will ask: Who is accountable at 2 a.m. when power quality drops and the mission systems start throwing errors?

The operating model must spell out:

- Authority boundaries between the vendor operator and the installation

- SLAs for uptime, response time, and power quality

- Cyber incident response roles (who isolates what, and when)

- Data rights for telemetry (critical for AI monitoring and audits)

If you want AI to optimize operations, you also need clean contractual pathways to access the data safely.

Addressing the two hard objections: targeting and fuel

The direct answer: risk management is real, and it’s solvable—but only with transparency and supply chain realism.

Objection 1: “A reactor becomes a target.”

The Army’s position, as reported, is that these are stateside installations, not forward-deployed fronts, and that microreactors contain small amounts of fissile material, making them unattractive proliferation targets.

Even if you accept that logic, bases are not immune to:

- Insider threats

- Drone overflight and reconnaissance

- Coordinated physical sabotage attempts

- Cyber-physical disruption

That means the program should treat each deployment as a combined security package:

- Physical security (standoff, access control, hardening)

- Cyber security (OT monitoring, segmentation, verified updates)

- Operational security (minimize public footprint of sensitive details)

Objection 2: “Fuel supply isn’t ready.”

Energy Department leadership has acknowledged the enrichment bottleneck and ongoing efforts to expand domestic capability. That’s a real constraint, not a talking point.

If the Army wants microreactors to become a repeatable template by 2028 and beyond, fuel supply needs to be treated like any other defense industrial base dependency:

- multi-source strategy where possible

- long-term procurement commitments

- inventory and transport planning

- realistic deployment pacing

AI can help here too—forecasting fleet-wide fuel requirements, planning refueling windows, and optimizing logistics. But AI can’t manufacture enrichment capacity. The industrial plan has to exist.

What leaders should do in 2026–2027 to make microreactors operationally real

The direct answer: start building the AI-ready, cyber-ready operating environment now—before concrete is poured.

If you’re a DoD energy, IT, cyber, or installation leader (or a contractor supporting them), this is the checklist that prevents a high-profile pilot from turning into a one-off:

- Define the mission-critical loads and the minimum assured power level (in megawatts) the base must maintain.

- Design the data architecture early: telemetry pipelines, retention, access controls, and audit trails.

- Write AI into the concept of operations: what AI monitors, what it recommends, and what humans must approve.

- Treat OT cyber as a primary requirement, not a compliance afterthought.

- Plan workforce training around incident management, not just normal operations.

- Run tabletop exercises that include grid loss, sensor anomalies, and coordinated cyber/physical disruption.

A practical rule: if you can’t explain how the system fails safely, you don’t understand the system yet.

The bigger picture for AI in Defense & National Security

Microreactors are easy to misread as an engineering curiosity. The reality is more strategic: assured energy expands what military AI systems can reliably do on-base—from continuous cyber monitoring to real-time logistics optimization to sustained compute for training and analytics.

The Army wants to break ground by 2027. That’s the visible milestone. The quieter milestone is the one that determines success: building an AI-first operations layer that makes the reactor, the microgrid, and the base behave like a resilient system.

If you’re building AI capabilities for defense and national security, ask yourself this: what would you deploy tomorrow if you had guaranteed power for the next five years—and what stops you today?

If your team is evaluating AI for critical infrastructure, installation resilience, or OT cyber defense, the fastest progress usually starts with a clear data and operating model—not a demo.