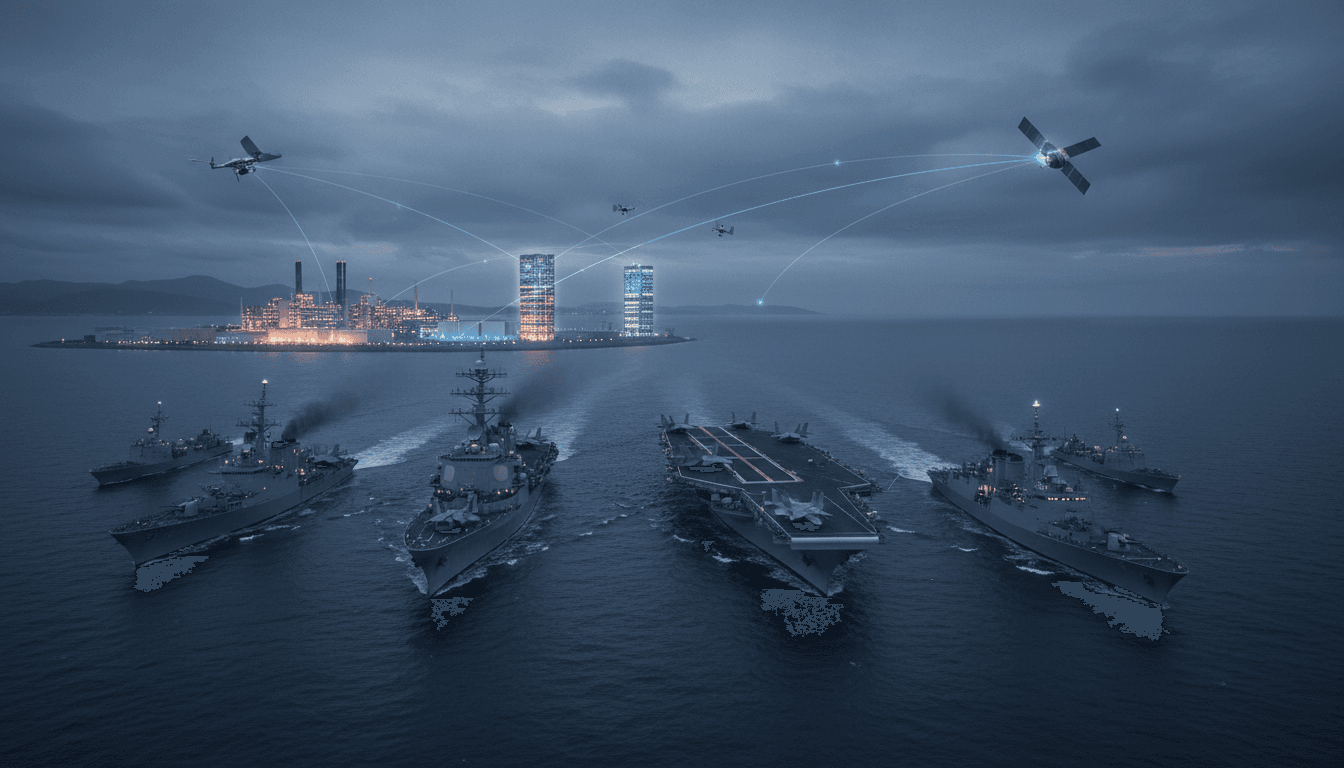

AI progress is now constrained by chips—and chips make Taiwan central to deterrence. Learn how compute shapes ISR, autonomy, and defense planning in 2026.

AI, Chips, and Taiwan: The New Deterrence Math

A single constraint is quietly shaping defense strategy across the Pacific: AI progress is now gated by compute, and compute is gated by advanced chips. That makes Taiwan—home to the world’s most critical leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing capacity—more than a geopolitical flashpoint. It’s a central node in the emerging AI security order.

A U.S. congressional hearing in late 2025 captured the mood shift. A decade ago, predictions of human-level AI arriving by 2029 sounded like sci-fi. Now the argument has moved from if to what happens to deterrence, intelligence, and industrial power if it arrives on schedule—and who controls the chip supply that fuels it.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, where we look at AI not as a lab curiosity but as a force multiplier (and vulnerability) across intelligence, surveillance, autonomous systems, cyber, and mission planning. The Taiwan case is a clean example: it shows how AI changes the strategic balance even before you field a single autonomous weapon.

The short version: AI makes Taiwan more strategic, not less

Answer first: As AI models scale, the value of secure access to advanced chips rises, and the strategic incentive to control chip supply chains rises with it. Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem becomes a direct factor in military planning, economic resilience, and coercive leverage.

For defense leaders, the mistake is thinking of Taiwan primarily as a regional contingency. The reality is broader: control over leading-edge manufacturing is a lever on global AI capability, which in turn affects everything from ISR processing capacity to autonomous platform training pipelines.

The logic chain is straightforward:

- Advanced AI capability requires massive compute.

- Compute at scale requires high-end GPUs/accelerators.

- Those accelerators depend on leading-edge nodes and advanced packaging.

- A large share of that manufacturing capacity remains concentrated in Taiwan’s ecosystem.

That concentration changes the risk calculus. Not because it guarantees any one outcome, but because it creates a strategic prize large enough to tempt coercion—and dangerous enough to demand serious contingency planning.

Why AI changes the timeline pressure

A notable claim raised in policy circles is that human-level AI (often described as AGI) could arrive around 2029. Whether or not you buy that date, the behavioral impact is already here: governments plan around perceived windows of advantage.

If senior decision-makers believe a decisive AI capability edge is achievable within a few years, you should expect:

- More aggressive efforts to secure chip supply (political, commercial, and covert)

- Stronger push to deny rivals access to high-end accelerators

- Increased emphasis on AI-enabled intelligence and targeting at operational tempo

This matters because deterrence isn’t just about forces in theater. It’s also about industrial capacity, tech denial, and resilience.

Chips are the fuel of AI-enabled ISR and targeting

Answer first: In modern defense, advanced chips aren’t just an economic commodity; they directly determine how much sensor data you can ingest, fuse, and exploit for decision advantage.

A lot of AI-in-defense discussions get stuck on the platform: drones, loitering munitions, autonomous vehicles. The less flashy reality is that the pipeline—collection to processing to action—wins fights.

Where chips show up in the kill chain

At a high level, AI-enabled ISR and targeting depends on compute in four places:

- Edge processing (onboard aircraft, drones, ships, ground vehicles)

- Forward-deployed processing (tactical clouds, expeditionary data centers)

- Strategic processing (national-scale fusion, large model training)

- Simulation and mission rehearsal (synthetic environments for planning and training)

Each layer benefits from accelerators—and each layer is constrained when chip supply tightens.

Here’s the hard truth I’ve found: the bottleneck is rarely “we don’t have an algorithm.” It’s usually one of these:

- Not enough compute to run models at operational scale

- Not enough bandwidth to move sensor data where compute exists

- Not enough power/cooling to deploy compute forward

- Not enough trusted supply chain assurance to put hardware on classified networks

Taiwan’s chip output influences all of those downstream realities.

AI surveillance is a volume problem

AI surveillance isn’t magic. It’s math plus throughput. When you can process more full-motion video, SAR imagery, EW intercepts, and open-source feeds—faster—you:

- Detect patterns earlier

- Reduce analyst overload

- Maintain tracking continuity on more targets

- Increase confidence in cueing and cross-cueing

That’s why chip access becomes a national security variable. It’s not just about who has “smarter AI.” It’s about who can run it more times, on more data, across more missions.

A Taiwan contingency is also an AI supply-chain contingency

Answer first: A crisis around Taiwan would disrupt not only consumer electronics but also the compute base that underpins AI model training, AI-enabled cyber defense, and autonomous system development.

During the 2025 hearing discussed in the source article, witnesses argued that a takeover or severe disruption could trigger a global depression because advanced chip flow would be choked. That’s a dramatic phrase, but the direction is right: the shock would be immediate.

From a defense and national security lens, the implications stack up quickly:

- Training stalls: Large-scale model training and fine-tuning become costlier and slower.

- Fielding slows: Programs relying on advanced accelerators face delays.

- Readiness erodes: Spare parts and refresh cycles for compute infrastructure break.

- Cyber risk rises: Under-supplied orgs patch slower and run older, more vulnerable stacks.

This is exactly why Taiwan’s chip capacity isn’t just an economic concern—it’s a strategic dependency.

The coercion angle: control beats destruction

There’s an uncomfortable point here. In a crisis, outright destruction of fabs harms everyone. But control and selective denial can be more tempting than sabotage.

If a competitor could:

- prioritize their own domestic AI and defense needs,

- shape who gets “enough” chips to stay afloat,

- and make rivals pay politically or economically for supply,

…they gain a form of leverage that looks less like a blockade and more like “market management.” That’s harder to counter, and it sits in the gray zone below open conflict.

The hidden AI arms race: compute, autonomy, and industrial scaling

Answer first: The decisive advantage won’t come from a single model; it will come from the ability to scale AI into production systems—factories, fleets, networks, and operational workflows.

One theme from the hearing was the fear that the U.S. becomes an AI “services economy” while a competitor applies AI at industrial scale. That’s not a culture-war talking point; it’s a defense readiness problem.

Why? Because defense logistics and force generation are industrial problems:

- building and repairing platforms,

- producing munitions,

- sustaining supply lines,

- turning raw sensor data into operational decisions.

AI helps only if it’s deployed into real processes with real constraints.

Autonomy depends on training loops

Autonomous systems—especially those operating in contested environments—need:

- massive simulation runs,

- frequent model updates,

- test-range data,

- red-team adversarial testing,

- and safe-guarded deployment pipelines.

All of that consumes compute. If you can’t access accelerators, you can’t run training loops fast enough to iterate and adapt. Autonomy becomes a supply-chain problem.

“Deny chips” is not a strategy by itself

Policy proposals like tightening export controls or requiring domestic prioritization of advanced chips (conceptually similar to “Americans first” supply mechanisms) can help. But denial-only approaches have three predictable weaknesses:

- Workarounds appear (gray markets, intermediaries, re-export).

- Domestic demand outpaces supply if manufacturing doesn’t expand.

- Allies get squeezed if controls are blunt and poorly coordinated.

A mature approach pairs restriction with capacity, coordination, and verification.

What defense and security leaders should do in 2026 planning cycles

Answer first: Treat compute as a strategic resource, design AI systems for degraded compute environments, and build procurement and governance that assumes supply shocks.

This is the part most teams can act on without waiting for legislation or a crisis.

1) Build a “compute readiness” dashboard

If you manage AI in defense programs, you should be able to answer these questions quickly:

- How many accelerators do we have across classified/unclassified environments?

- What percentage are mission-critical vs. experimental?

- What’s the refresh cycle, and what fails if procurement slips by 6–12 months?

- What workloads can be shifted to CPUs or smaller models if GPUs are constrained?

Compute readiness belongs alongside cyber readiness and supply readiness.

2) Engineer for graceful degradation

Most companies get this wrong: they design AI systems assuming cloud-scale compute will always be there.

Defense AI should assume the opposite. Useful design patterns include:

- tiered models (small model at edge, larger model at rear)

- bounded autonomy (fail-safe modes when confidence drops)

- offline-first workflows (store-and-forward, resilient caching)

- model compression (

quantization,distillation) for forward deployments

These aren’t academic tricks. They’re how you keep ISR and decision support running when logistics and procurement get ugly.

3) Prioritize data fusion over “bigger models”

A strong stance: fusion beats size in many military contexts.

If you improve:

- sensor tasking,

- cross-cueing,

- entity resolution,

- and uncertainty tracking,

…you can often outperform a larger model fed with messy inputs. That reduces compute demand while raising operational value.

4) Treat semiconductor and packaging visibility as mission assurance

Risk management needs to include:

- provenance tracking for high-end accelerators,

- trusted hardware pathways for classified networks,

- contingency suppliers for networking, power, and cooling components,

- and clear red lines for counterfeit and tampered hardware.

This is where commercial best practices (supply-chain security, component attestation) meet national security realities.

Snippet worth remembering: If your AI strategy doesn’t include a chip strategy, you don’t have an AI strategy—you have a prototype.

What this means for deterrence in the Taiwan Strait

Answer first: AI intensifies deterrence requirements by raising the value of chip access, increasing ISR processing tempo, and rewarding the side that can sustain compute under disruption.

Deterrence used to focus on ships, missiles, and aircraft in the right places. That’s still true. But the AI era adds new pillars:

- Compute endurance: Can you keep models running during sanctions, blockades, or supply shocks?

- ISR throughput: Can you process more of the battlespace faster than your opponent?

- Industrial adaptability: Can you surge production and sustainment with AI-assisted logistics and manufacturing?

As we head into 2026, I expect serious defense organizations to separate themselves not by who demos the flashiest agent, but by who can:

- field reliable AI-enabled ISR at scale,

- maintain trusted compute stacks,

- and operate effectively when advanced chips are constrained.

If you’re building or buying AI for defense and national security, the Taiwan lesson is blunt: geopolitics is now part of your system architecture. What are you doing today to make sure your AI capabilities survive tomorrow’s supply chain shock?