AI-powered robot dogs with arms are moving from sensing to real work. See what mobile manipulation changes for defense, security, and automation teams.

AI-Powered Robot Dogs With Arms: What Changes Now

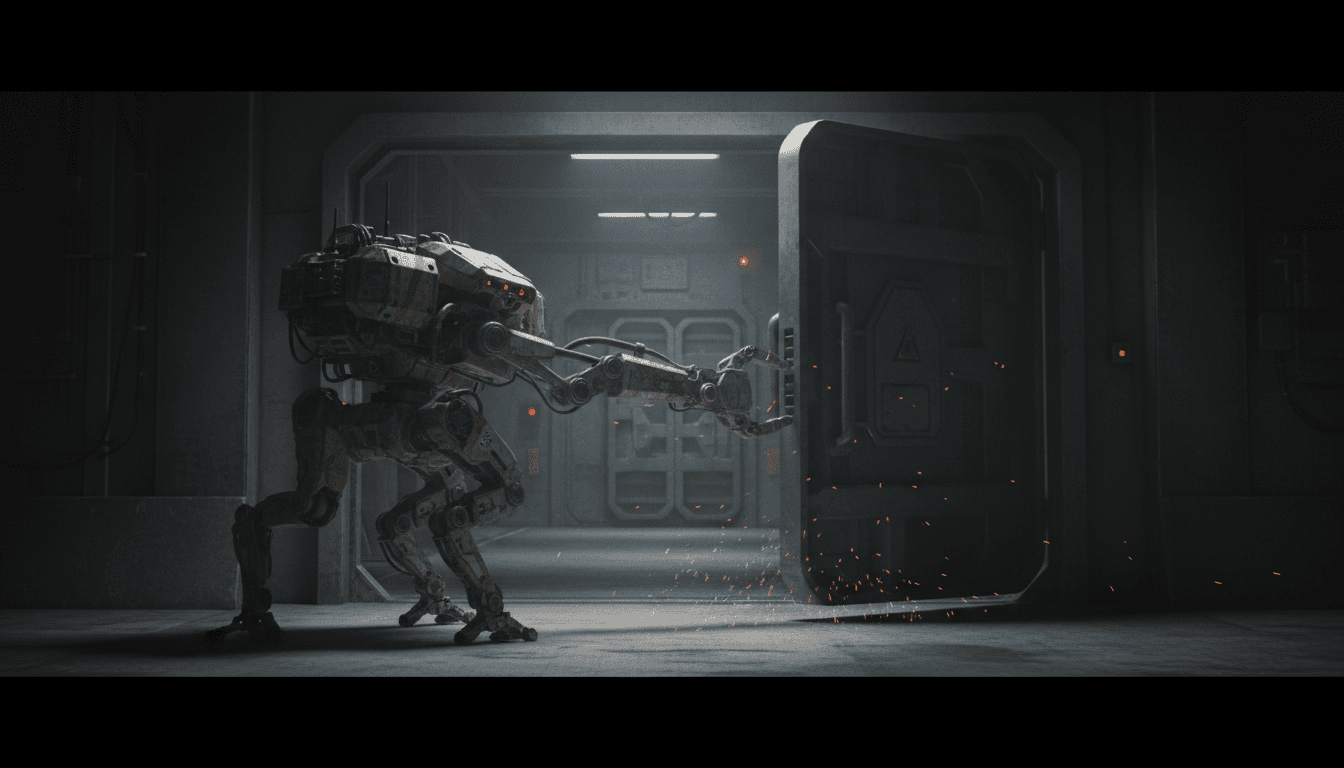

A quadruped robot that can walk anywhere is impressive. A quadruped robot that can walk somewhere and then do something once it gets there is the version that changes operations.

That’s why Ghost Robotics adding a manipulator arm to its Vision 60 matters. Not because “robot dogs” are trendy again, but because mobile manipulation is the practical step from “remote sensor platform” to “remote work platform.” In defense and national security, that means fewer humans standing in doorways, stairwells, and exposed corridors. In commercial settings, it means fewer people doing dull, risky, repetitive physical tasks in places built for humans.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, where we track how autonomy, perception, and robotics are shifting real-world mission workflows. The Vision 60 arm is a clean case study: rugged mobility plus AI-assisted manipulation plus policy constraints equals a new class of field automation.

The real upgrade: mobility without manipulation is a half-solution

Legged mobility solves “get there.” Manipulation solves “finish the job.” Most organizations evaluating quadrupeds (military, utilities, critical infrastructure, industrial sites) hit the same wall: the robot can traverse terrain, but it can’t interact with the world.

Doors, gates, backpacks, straps, valves, drawers, sample containers—these are the real blockers. A robot that can only observe turns missions into “send the robot, then send a human anyway.” That’s not operationally efficient, and in defense contexts it defeats the safety objective.

Ghost’s Vision 60 arm puts a number on the intent:

- Arm payload: up to 3.75 kg

- Degrees of freedom: 6-DoF (enough for practical reaching, grasping, and positioning)

- Platform ruggedness: the robot can be submerged to 1 meter, sealed against dust/sand, and operate from -40 °C to 55 °C

Those details matter because mobile manipulation fails fast if the arm can’t survive real field abuse—drops, collisions, and the robot rolling over.

Why AI matters more than the arm hardware

An arm isn’t automatically useful just because it exists. The useful part is AI-assisted perception + control:

- Perception to recognize handles, hinges, latches, straps, and “where to grab”

- Estimation to understand pose and contact points in clutter

- Control to maintain stability while applying force (whole-body control)

In practice, the win isn’t “full autonomy” 100% of the time. The win is reducing operator burden so a human can provide high-level intent (“open that door,” “pull that bag,” “take a sample”) while the robot handles the messy geometry.

Why the Vision 60 arm is being treated like a “fifth leg”

Ghost’s CEO described the arm as morphologically a fifth leg, and I think that framing is exactly right.

Answer first: A manipulator on a legged robot can’t be designed like a warehouse cobot arm—it has to be integrated into balance, gait, and contact planning.

Here’s what changes when the arm is part of whole-body control:

- Stability management: opening a stuck door is a force problem; the robot has to counter-torque without slipping.

- Contact-aware planning: the robot may brace with the arm, or use it to stabilize during a step.

- Recovery behavior: if the platform falls, the arm must tolerate impact and not become a single point of failure.

This is where AI-enabled robotics earns its keep. Classic manipulation pipelines assume stable bases. Field quadrupeds assume the opposite.

The “door problem” is a proxy for a whole category of tasks

Door opening gets attention because it’s visually clear—and because it’s operationally important—but it’s shorthand for a bigger set:

- Moving obstacles: chairs, bags, debris, loose materials

- Operating infrastructure: latches, covers, handles, basic controls

- Sampling and retrieval: swabs, air samples, small objects

- Positioning sensors: raising a camera, placing a probe, peeking over barriers

That last one—using the arm as a sensor boom—is a telling customer-driven use case. It says buyers don’t just want “robot hand.” They want better viewpoints without exposing the entire robot.

Defense relevance: keep humans away from the “last meter”

In defense and national security operations, the most dangerous space is often the final approach: the doorway, the corner, the stair landing, the threshold.

Answer first: AI-powered mobile manipulation shifts risk away from humans by letting robots perform the last-meter interaction tasks that traditionally require a person.

Examples of tasks where this matters:

- Recon plus access: approach a structure, inspect, then open a door or gate

- Route clearance support: move lightweight obstructions, pull suspicious items to a safer distance

- CBRN and hazardous sampling: take samples without sending a technician forward

- Perimeter checks: lift/adjust small objects, reposition sensors, inspect with better angles

These aren’t hypothetical “sci-fi autonomy” scenarios. They’re the annoying, frequent, expensive mission steps that burn time and expose people.

The uncomfortable topic: weaponization vs. capability

Once you add a strong platform and a manipulator, people naturally ask about weaponization. That debate is real—and it’s not going away.

But capability and weaponization aren’t identical. Mobile manipulation is broadly dual-use:

- The same arm that opens doors can also remove a trip hazard in a factory.

- The same sensor boom use case maps directly to industrial inspection.

- The same ruggedization requirements show up in mining, offshore energy, and disaster response.

Policy frameworks also exist. In the U.S., systems connected to autonomy in weapon contexts fall under directives that require human judgment for use-of-force decisions. That doesn’t “solve” the ethics debate, but it does shape procurement requirements: auditability, operator control, and documented safeguards.

China’s quadruped cost pressure is the drone story repeating

The most strategically important part of the story isn’t the arm. It’s the market dynamics.

Answer first: Legged robots are heading toward the same pattern as drones: subsidized low-cost platforms force everyone else to justify security, reliability, and domestic supply.

The RSS article referenced two sobering signals:

- DJI’s global drone market share has been estimated around 90% in recent years.

- Unitree has been estimated around 70% share in quadrupeds.

Whether those numbers shift up or down, the point holds: cost collapses adoption barriers, and adoption creates dependencies. For defense and critical infrastructure buyers, that becomes a security question, not a purchasing question.

This is where AI in defense intersects supply chain reality:

- If your robotics fleet is a sensor network, then data paths are mission paths.

- If your platform vendor is compromised, your autonomy stack can be compromised.

- If you can’t patch or validate firmware/software behavior, “cheap” becomes expensive.

For commercial buyers, the calculus is similar but less existential: downtime, safety certification, and supportability matter more than sticker price once robots are deployed at scale.

What non-military automation teams should learn from this

It’s tempting to treat defense robotics as a separate universe. I don’t.

Answer first: Military-grade mobile manipulation is a preview of what warehouses, utilities, and heavy industry will adopt next—because the environments are similarly messy.

Here are the direct bridge points to commercial automation:

1) Warehousing and logistics: the missing “hands” problem

Warehouses already have robots that move shelves and pallets, but edge cases still require people:

- Picking dropped items

- Clearing jammed aisles

- Opening roll-up doors and gates

- Moving lightweight clutter that blocks navigation

A legged base with manipulation isn’t the answer for every facility. But for mixed environments (stairs, uneven floors, temporary layouts), it can be the pragmatic “gap filler” between fixed automation and human labor.

2) Utilities and critical infrastructure: inspection + intervention

Utilities don’t just need inspection images; they need small interventions:

- repositioning sensors

- opening access panels

- placing probes

- pulling samples

Ruggedization—dust sealing, water resistance, temperature tolerance—isn’t a “nice-to-have” here. It’s table stakes.

3) Healthcare and emergency response: remote handling in constrained spaces

Hospitals and emergency response share one trait with defense: risk management under uncertainty. Mobile manipulation supports tasks like moving objects, handling samples, and assisting in environments where a wheeled robot can’t reliably operate.

If you’re evaluating quadrupeds with arms, focus on these requirements

Most companies get evaluation backwards: they start with demos and end with integration regret. Here’s what works.

Build your use cases around force, not just motion

Opening a door isn’t “reach and pull.” It’s contact dynamics. Ask:

- What forces are expected (push/pull/torque)?

- What happens when the handle doesn’t turn?

- Does the robot regrasp and retry safely?

Treat autonomy as operator workload reduction

You don’t need a robot that’s autonomous on paper. You need one that reduces labor in practice.

Define success metrics like:

- time-on-task reduction per mission

- number of operator interventions per minute

- recovery time after failed grasps

Demand whole-stack observability

If the robot is operating in high-stakes environments, you need:

- logs of perception outputs and decisions

- replayable mission data

- clear remote override modes

That’s how you audit incidents and improve reliability without guesswork.

Plan for field service and modular repair

Ghost highlighted quick leg swaps in the field. That’s not trivia; it’s operational readiness.

Your checklist should include:

- module swap time (minutes, not hours)

- spare parts strategy

- battery swap strategy

- environmental sealing after service

Where AI-powered mobile manipulation goes next

The next phase isn’t “robots that look cooler.” It’s robots that do more of the mission with fewer humans micromanaging them.

Expect near-term progress in:

- semantic manipulation (robot understands “handle,” “latch,” “strap,” not just shapes)

- better failure recovery (regrasping, repositioning, adaptive force)

- multi-robot workflows (one robot scouts, another manipulates, a third carries payload)

Longer term, the differentiator will be trust: repeatability, safety, cybersecurity, and clear accountability in how autonomy behaves.

A legged robot without manipulation is a camera with feet. Add AI-powered manipulation and it becomes a remote worker.

If you’re building or buying robots for defense, critical infrastructure, or industrial operations, the question to ask going into 2026 is simple: Which tasks still force a human to take the last step—and what would it take to make the robot finish the job?