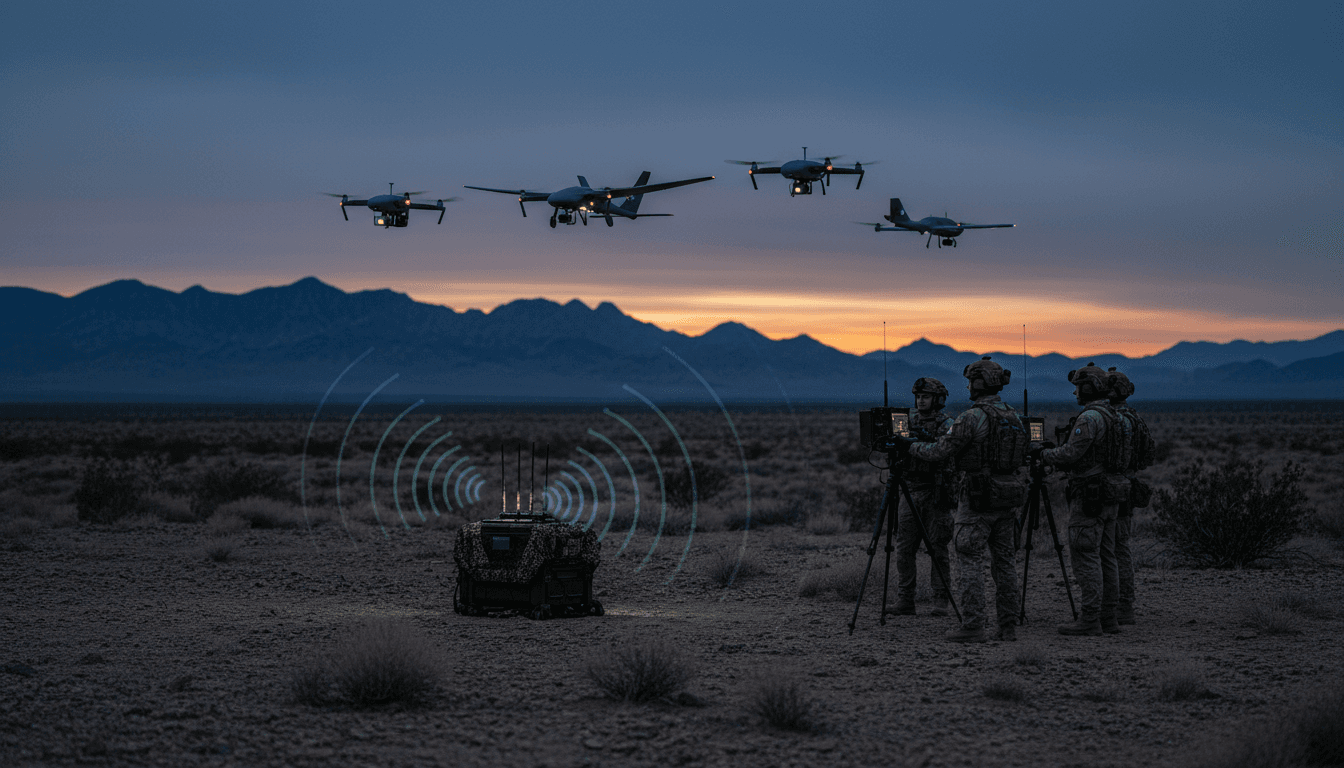

Special operators want more EW-capable ranges to train in GPS-denied environments. Here’s how AI-ready test sites can validate autonomy and EW fast.

AI-Ready EW Ranges: Train Drones Where GPS Fails

The U.S. military has two primary places where GPS and cellular jamming can happen regularly: White Sands Missile Range and the Nevada Test and Training Range. That’s not a trivia fact. It’s a constraint that shapes what’s possible in electronic warfare (EW) training and drone development—especially for special operations forces preparing for the kind of signal-chaos that now shows up in real combat.

Special operators are pushing to expand the areas where they can legally jam GPS and cellular signals in the U.S. to better simulate modern warfare conditions. They’re right to push. If you can’t train in the environment you’ll fight in, you’re not “behind”—you’re practicing the wrong sport.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, and I’m going to take a clear stance: expanding EW-capable training ranges isn’t just a range problem. It’s an AI readiness problem. The next step isn’t only more airspace and spectrum approvals—it’s building AI-enabled test ecosystems where autonomy, perception, and EW can be validated safely, repeatedly, and at scale.

The real bottleneck: you can’t train autonomy without realistic EW

Answer first: Autonomous drones and AI-enabled systems can’t be trusted in combat until they’re tested against the same EW pressure they’ll face in combat—GPS denial, spoofing, cellular disruption, and noisy spectrum environments.

The RSS report describes a practical operational gap: U.S. special warfare trainers want expanded areas to jam GPS and cellular signals so students can train under realistic conditions. The urgency is driven by battlefield lessons from Ukraine, where EW has forced rapid adaptation—like drones controlled by fiber-optic cable and drones with more onboard autonomy that reduces reliance on jam-prone links.

Here’s the core issue: EW isn’t an “add-on” anymore. It’s the environment. That changes what training ranges must provide.

Ukraine’s lesson is blunt: EW punishes assumptions

On the modern battlefield, assumptions fail fast:

- Assume GPS is available? You’ll learn what GPS-denied navigation actually means.

- Assume your command link stays clean? You’ll meet jammers, interference, and spoofing.

- Assume humans can manually pilot everything? You’ll hit scale limits and reaction-time limits.

That’s why special operators are asking regulators to create more jammable airspace and spectrum windows: realistic training now requires realistic disruption.

Why AI makes this harder—and more necessary

AI systems learn patterns. They also learn the wrong patterns if you only train them in “clean” conditions.

If you’re developing AI for:

- autonomous drone operations

- onboard target recognition

- electronic support (signal detection and classification)

- mission planning in contested environments

…then EW must be present during data collection, testing, and evaluation. Otherwise, your models look great in demos and fail in the one place that matters.

What expanded EW ranges should look like in 2026 (and why)

Answer first: Expanded EW ranges should be treated like an integrated “AI proving ground,” not a bigger sandbox for jammers—combining spectrum effects, autonomy testing, safety controls, and rapid iteration loops.

The RSS article highlights how civil restrictions make it difficult to train on U.S. soil, and how approvals often require complex coordination with agencies like the FAA and FCC. That’s real. But even if those permissions expand, the U.S. still needs a plan for what to build inside those permissions.

Here’s a practical blueprint for AI-ready EW ranges.

1) Spectrum realism: controlled chaos, not random interference

EW training can’t just mean “turn on a jammer.” It should include:

- GPS jamming at variable power levels and geometries

- GPS spoofing scenarios (false position/time)

- cellular and ISM-band interference patterns that mimic urban and battlefield clutter

- multi-emitter environments (friendly + adversary + civilian-like signals)

Why? Because AI models need diverse, labeled exposure to signal conditions to generalize well.

2) Instrumentation: every flight is a data collection event

If ranges expand, the biggest missed opportunity would be treating them like old-style training lanes.

An AI-ready range should capture:

- RF snapshots (IQ data where feasible)

- navigation truth vs. perceived state (GPS/INS/vision)

- link quality metrics (latency, packet loss, dropouts)

- onboard autonomy decisions (why the drone chose a route or action)

This matters because model improvement depends on high-quality, replayable telemetry. You want the ability to say, “The drone failed at T+138 seconds because spoofing shifted time sync by X ms and the planner didn’t degrade gracefully.”

3) Safety and governance: autonomy needs guardrails

The more autonomous the system, the more the range needs:

- geofencing enforcement independent of GPS (because GPS may be denied)

- kill-switch mechanisms that don’t rely on the primary command link

- pre-approved “EW windows” with clear public safety boundaries

- red-team oversight so you’re not grading your own homework

If you’re serious about autonomous systems in defense, range safety architecture becomes part of national security infrastructure.

AI’s role in electronic warfare training: beyond “smarter drones”

Answer first: AI improves EW training and operations by enabling real-time signal understanding, predicting jamming impact, and stress-testing autonomy at battlefield tempo.

The campaign angle here isn’t “AI everywhere.” It’s narrower and more useful: AI can turn expanded ranges into repeatable, measurable learning systems.

AI for signal intelligence and electronic support

Modern EW environments generate more signals than human analysts can process in real time. AI helps by:

- classifying emitters quickly (known, unknown, deceptive)

- detecting anomalies (spoofing signatures, unusual hopping patterns)

- prioritizing threats based on proximity, intent cues, and mission phase

This is where training ranges matter: models need real RF conditions to avoid brittle performance.

AI for predicting jamming effects before you flip the switch

One of the frictions described in the RSS content is the bureaucracy and planning required for GPS disruption events. AI can reduce friction by forecasting:

- likely spillover impact zones

- risk to nearby aviation routes

- expected outage duration by geography

You still need governance. But better prediction helps regulators approve more events because the risk story is clearer and quantified.

AI for autonomy under EW pressure

Autonomy isn’t a binary state. Under EW, good autonomy looks like:

- graceful degradation when navigation confidence drops

- switching to alternate positioning (inertial, visual, terrain)

- changing routes to reduce exposure to known emitters

- reducing RF emissions (“quiet mode”) when needed

These behaviors can be trained and tested—but only if the range can reproduce EW conditions repeatedly.

The workforce angle: training robot techs is necessary, but not sufficient

Answer first: The military needs more than drone operators and robot technicians—it needs an AI-literate EW workforce that can iterate systems in weeks, not years.

The RSS report mentions new initiatives: a tactical signal intelligence and electronic warfare course, a robotics detachment launched in 2024, and a new specialist role for robot technicians. That’s the right direction.

The next step is making sure the pipeline produces people who can:

- tune autonomy behaviors based on EW telemetry

- understand model limitations and failure modes

- validate perception systems under degraded sensing

- run disciplined experiments (not vibes-based testing)

What “AI-literate EW training” should include

If I were designing the syllabus additions, I’d include:

- EW-informed autonomy testing: students run the same mission profile across varying jamming/spoofing conditions and learn to interpret outcomes.

- Dataset hygiene in contested environments: labeling, versioning, and bias checks when data is collected under interference.

- Red-team autonomy: adversarial scenarios that attempt to trigger unsafe behaviors.

- Operational UX: how humans supervise autonomy when screens lie and links degrade.

If your training doesn’t teach how systems fail, you’re producing confidence—not capability.

Practical next steps: how agencies and vendors can act now

Answer first: You don’t have to wait for brand-new mega-ranges—start by building portable, AI-instrumented EW test packages and standardizing how results are measured.

Range expansion and regulatory coordination take time. Meanwhile, programs can still move.

A near-term playbook (90–180 days)

- Create “EW-in-a-box” training kits for approved sites: instrumented low-power interference tools, logging, safety controls, and repeatable scenarios.

- Standardize success metrics for autonomy under EW: navigation error bounds, mission completion rates, link loss recovery time, target ID accuracy under degradation.

- Build a shared evaluation harness so units and labs compare results apples-to-apples.

A mid-term playbook (6–18 months)

- Federate multiple smaller ranges into a single scheduling and data framework (a range network, not isolated sites).

- Expand jamming approvals through risk-based templates: repeatable documentation packages that reduce rework.

- Establish “digital twin + live” test cycles: simulate first, then validate in live EW windows.

That last point matters: the best teams will run thousands of simulated reps, then use live range time for validation—because live EW time will always be scarce.

Where this goes next for AI in Defense & National Security

EW-capable ranges are becoming as foundational as runways and shipyards. If the U.S. wants reliable autonomous drone operations, it needs places to prove those systems under stress—legally, safely, and often.

The uncomfortable discussion special operators referenced—about carving out airspace and spectrum for jamming—should expand into a bigger one: are we building the training infrastructure that AI-enabled warfare requires, or are we trying to bolt AI onto a 2005-era range model?

If you’re responsible for autonomy, EW, training, or test and evaluation, a useful next step is to map your program against three questions:

- Can we collect and replay EW-affected flight data at scale?

- Can we measure autonomy performance under GPS denial and spoofing with objective metrics?

- Can we iterate quickly—new models, new tactics, new countermeasures—without waiting a year for range access?

If the answer is “not yet,” that’s the real requirement. Not just bigger ranges—AI-ready ranges.