Inside JPMRC 2025: 75 technologies, AI-ready C2, drones, and hard lessons on speed, trust, and contested networks for modern Army training.

AI-Ready Army Training: What JPMRC Proves in 2025

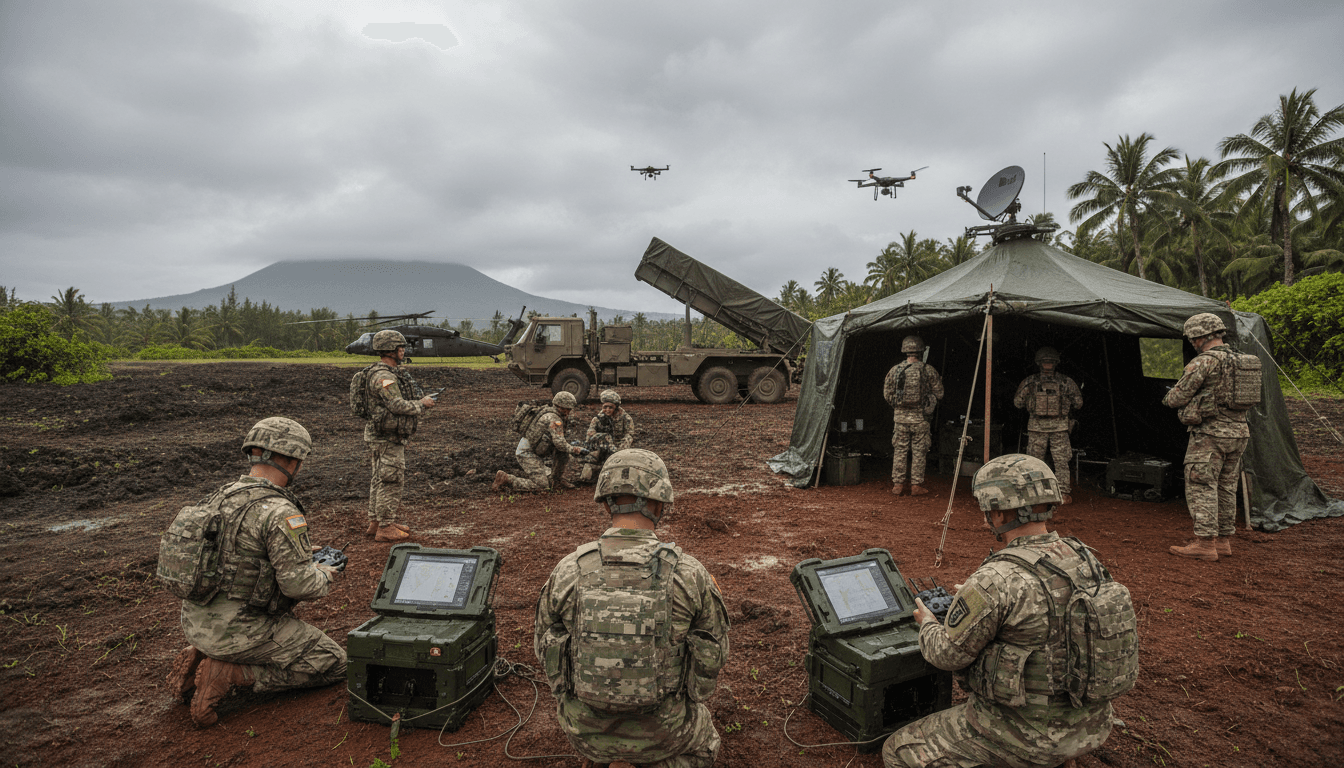

A two-week Army exercise in Hawaii tested 75 new technologies in a single rotation. That number is the headline—but it’s not the story.

The story is that the Army is finally treating training as a full-stack systems test: sensors, networks, autonomy, targeting workflows, sustainment, and human decision-making—all under pressure, all at once. For anyone working in defense tech, national security, or government innovation, the Joint Pacific Multinational Readiness Center (JPMRC) rotation is a clear signal: the force isn’t just buying modern tools. It’s trying to relearn how to fight with them.

This post sits in our “AI in Defense & National Security” series, where we track how AI-enabled capabilities move from demos to missions. JPMRC matters because it’s where promising AI and autonomy concepts run into reality: contested communications, approval bottlenecks, cognitive overload, and the hard physics of distance in the Indo-Pacific.

JPMRC shows the new baseline: multi-domain, AI-assisted, fast

The practical lesson from JPMRC is simple: modern land warfare is multi-domain by default, and AI-enabled tools are being judged on whether they shorten the time from sensing to decision to effects.

In the Hawaii rotation, the scenario simulated defending an archipelago and retaking islands. The exercise involved every U.S. service branch plus seven partner nations, and included high-mobility missions like flying HIMARS on C-17s to a remote airfield for a simulated raid and returning them quickly. This is the Indo-Pacific problem set in one sentence: distance and dispersion punish slow coordination.

AI’s role here isn’t a single “system.” It’s the glue that turns a pile of sensors, drones, and fires into a decision advantage:

- Autonomous and semi-autonomous reconnaissance extends what units can see without exposing people.

- Algorithmic fusion and prioritization helps decide what matters when you’re flooded with feeds.

- Decision support can compress planning cycles—if the organization trusts the outputs.

Here’s my stance: if your modernization plan doesn’t measurably reduce the time it takes to detect, understand, decide, and act, you’re not modernizing—you’re shopping.

“Transformation in Contact” is really about closing the learning loop

The Army’s “transformation in contact” effort is often described as rapid modernization. In practice, it’s an attempt to fix the slowest part of defense adoption: feedback cycles.

At JPMRC, senior leaders were there to do something that sounds basic but is surprisingly rare at scale: collect frank input from soldiers about what worked and what failed, then push fixes quickly. The point is not perfection in the first fielding. The point is speed of iteration.

Failure modes the exercise surfaced (and why AI makes them worse)

One example from the rotation: new technology sped up targeting information, but approvals for fires sometimes still took around an hour because the process didn’t change. That’s the trap.

When you add AI-enabled speed to old workflows, you often get:

- Faster data entering a slow approval chain

- More alerts than humans can triage

- More “visibility,” but not more action

The Army vice chief’s observation—introducing tech without updating the process—should be printed on every acquisition slide deck. AI doesn’t just add capability; it exposes organizational latency.

What high-performing units do differently

Tech-forward units tend to share three behaviors:

- They treat exercises like product tests. You don’t “evaluate” once; you iterate weekly.

- They’re explicit about decision rights. Who can approve what, at what confidence level, under what conditions.

- They measure time-to-effect. Not “we had a drone,” but “we reduced detection-to-decision from X minutes to Y.”

If you’re building AI for defense customers, align your success criteria with those behaviors. Demos won’t survive contact. Metrics might.

Drones, loitering munitions, and the real shift: effects as a portfolio

The most extractable insight from JPMRC is that “artillery” is turning into an effects portfolio: rockets, tubed artillery, loitering munitions, one-way attack drones, reconnaissance drones, spoofing drones, and electronic warfare effects—all coordinated.

The Army is trying to answer a question that Ukraine has forced onto every military planner: What’s the right mix of mass, precision, and endurance?

Traditional artillery still matters. The exercise discussion referenced the reality of high-volume fires in Ukraine—thousands of 155mm rounds per day and on the order of 130,000–150,000 rounds per month in some periods. That’s not trivia; it’s a budgeting and logistics reality check.

Where AI fits in the effects portfolio

AI matters less as “a weapon” and more as the coordinator across a messy set of options:

- Target recognition and classification from ISR feeds (especially under time pressure)

- Sensor-to-shooter matching (which shooter, which munition, which timing)

- Deconfliction across airspace, frequencies, and friendly maneuver

- Electronic warfare-aware planning (what comms will survive, what won’t)

A useful one-liner for teams designing this: the kill chain is now a scheduling problem under uncertainty. AI is well-suited to scheduling—humans are not.

Next-generation command and control: the quiet center of gravity

The most important theme in the exercise wasn’t the drones. It was the network and command-and-control (C2) layer.

The Army is fielding next-generation C2 prototypes into full divisions (including the 25th and 4th). The goal is direct: maintain shared understanding after units cross the line of departure, even when connectivity degrades.

Why AI-ready networks beat “AI apps”

Organizations love to talk about AI models. Warfighters care about whether the system works when:

- bandwidth drops,

- nodes move,

- adversaries jam,

- and the environment is wet, muddy, and chaotic.

An “AI-ready” C2 network has specific characteristics:

- Edge processing so critical functions don’t depend on a perfect backhaul

- Graceful degradation (a partial picture beats a blank screen)

- Data interoperability across services and partners

- Security baked into data flows, not stapled on later

If you’re chasing leads in defense AI, this is where budgets and pain live: mission planning, contested networking, sensor fusion, and resilient data transport.

The human constraint: cognitive overload and trust calibration

One of the most honest moments from the exercise was a brigade commander describing “cognitive overload”—and then physically pulling out a paper map as the ultimate fallback.

That’s not anti-tech. It’s a reminder: humans are the bottleneck when systems multiply.

AI that helps in training—and AI that breaks teams

AI helps when it:

- reduces decisions, not adds them,

- explains why it recommends something,

- and lets operators set thresholds (what counts as “urgent”).

AI breaks teams when it:

- produces constant low-confidence alerts,

- forces people to babysit dashboards,

- or hides assumptions behind a black box.

In practical terms, the Army’s challenge is trust calibration. Not “trust AI” or “don’t trust AI,” but “trust it appropriately for this mission, at this risk level, with this fallback plan.”

A training takeaway worth stealing for any program office: require every AI-enabled capability to ship with three playbooks.

- Normal ops: what operators do when the system is healthy

- Degraded ops: what to do when confidence drops or links fail

- Denied ops: what the analog/manual fallback is

If your vendor can’t describe degraded and denied modes crisply, they’re not ready for operational training.

What leaders should copy from JPMRC (a practical checklist)

JPMRC isn’t just an Army story. It’s a template for any defense organization trying to integrate AI, autonomy, and modern networks.

Here’s a checklist I’d use to evaluate whether an AI-enabled modernization effort is real or performative:

- Do you test in contested conditions? If the demo assumes perfect comms, it’s a lab project.

- Do you measure decision-cycle time? Track detection-to-decision-to-effect, not “number of systems fielded.”

- Do you change authorities and workflows? Otherwise AI speed hits a policy wall.

- Do you train cognitive load management? Fewer screens, better triage, clear roles.

- Do you iterate on-week timelines? Weeks, not years, for fixes to training-discovered issues.

These aren’t abstract best practices. They’re the difference between a force that can adapt mid-campaign and a force that needs a new acquisition program every time reality changes.

Where this is heading in 2026: continuous transformation, not one-off upgrades

The Army’s leadership message coming out of JPMRC is that modernization has moved from “versioned” change to continuous transformation. That’s exactly where AI in defense has to go: constant model updates, evolving tactics, frequent red-teaming, and rapid feedback from the field.

For defense tech teams, the opportunity is also the warning: the hard part isn’t building a model—it’s deploying a system that survives friction. Indo-Pacific distances, partner interoperability, electronic warfare, and human overload will punish anything fragile.

If you’re building or buying AI for mission planning, autonomous systems, ISR analysis, cybersecurity, or next-generation C2, you should be asking a pointed question right now: are we training the organization to use this capability at speed, under risk, with imperfect information?

If not, you’re not preparing for modern warfare. You’re preparing for a briefing.