Affordable missile mass is only half the solution. AI-driven planning, targeting, and production math determine whether stockpiles last in a peer conflict.

Missile Stockpiles and AI: Winning the Magazine Fight

A modern missile fight isn’t decided by a single “best” weapon. It’s decided by math: how many interceptors you can afford to fire, how fast you can replace them, how well you can allocate them, and how accurately you can predict what you’ll need next week—not next year.

That’s why the most uncomfortable truth in U.S. defense planning right now is simple: the United States doesn’t have the magazine depth for a long, high-intensity fight against a peer competitor. If you can’t sustain missile expenditure rates, the exquisite capability you bought becomes a short-lived advantage.

The War on the Rocks discussion “Missiles and the Math of Modern Warfare” centers on a core problem—traditional missiles cost too much to build at scale—and a new wave of builders (Mach Industries, Castelion, Anduril) betting they can produce missiles in volume at dramatically lower cost. I agree with the direction, but I’ll be blunt: cheap missiles alone won’t fix the magazine problem. The winning approach is cost + production + operational AI—because the “math” is increasingly an AI problem.

The real constraint: missiles are a budget-and-time equation

The decisive constraint in modern warfare is sustained fires, not maximum performance on day one. If your adversary can keep launching and you can’t keep intercepting or striking back, the tactical picture collapses into a logistics story.

Here’s the basic magazine equation that planners wrestle with:

- Inventory: how many rounds exist today

- Burn rate: how many are used per day under realistic conditions

- Replenishment: how many can be produced per month (and how quickly they can be delivered)

- Effectiveness: how many shots it takes to achieve the desired probability of kill

That last line—how many shots per outcome—is where the “math of missiles” becomes unforgiving. A doctrine that requires two interceptors per inbound threat doubles your consumption instantly. A targeting process that over-allocates weapons “just in case” quietly empties your magazines.

Why high-end missiles don’t scale

The U.S. model has often favored small quantities of very expensive weapons, optimized for performance and survivability. Against limited adversaries, that approach can work. Against a peer with mass, deception, and a long fight in mind, it’s risky.

Scaling is hard for structural reasons:

- Specialized components can have long lead times and thin supplier bases.

- Quality assurance regimes are essential but can slow throughput if they’re not designed for volume.

- Workforce and facilities can’t be conjured instantly during a crisis.

The result is a gap between what war plans assume and what factories can actually sustain.

Lower-cost missiles matter—but only if they fit the way wars are fought

The War on the Rocks episode highlights a growing set of companies aiming to build missiles at orders-of-magnitude lower cost than traditional primes. That ambition is directly aligned with what the U.S. needs: more shots, faster replenishment, acceptable performance.

But the “cheap missile” idea fails if it’s treated as a procurement novelty rather than an operational concept.

The capability mix that actually closes the gap

A credible magazine strategy needs at least three layers:

- High-end weapons for the hardest targets (integrated air defense, hardened sites, high-value platforms)

- Medium-cost, mass-producible missiles that can be bought in real numbers

- Attritable munitions (including loitering systems) for saturation, decoys, and forcing adversary expenditure

This layered approach changes the math of exchange ratios. The goal isn’t to make every missile cheap; it’s to ensure the average cost per required effect is sustainable.

A force that can’t afford to fire is a force that can’t deter.

That line may sound harsh, but it’s the logic adversaries use when they calculate whether your threats are credible.

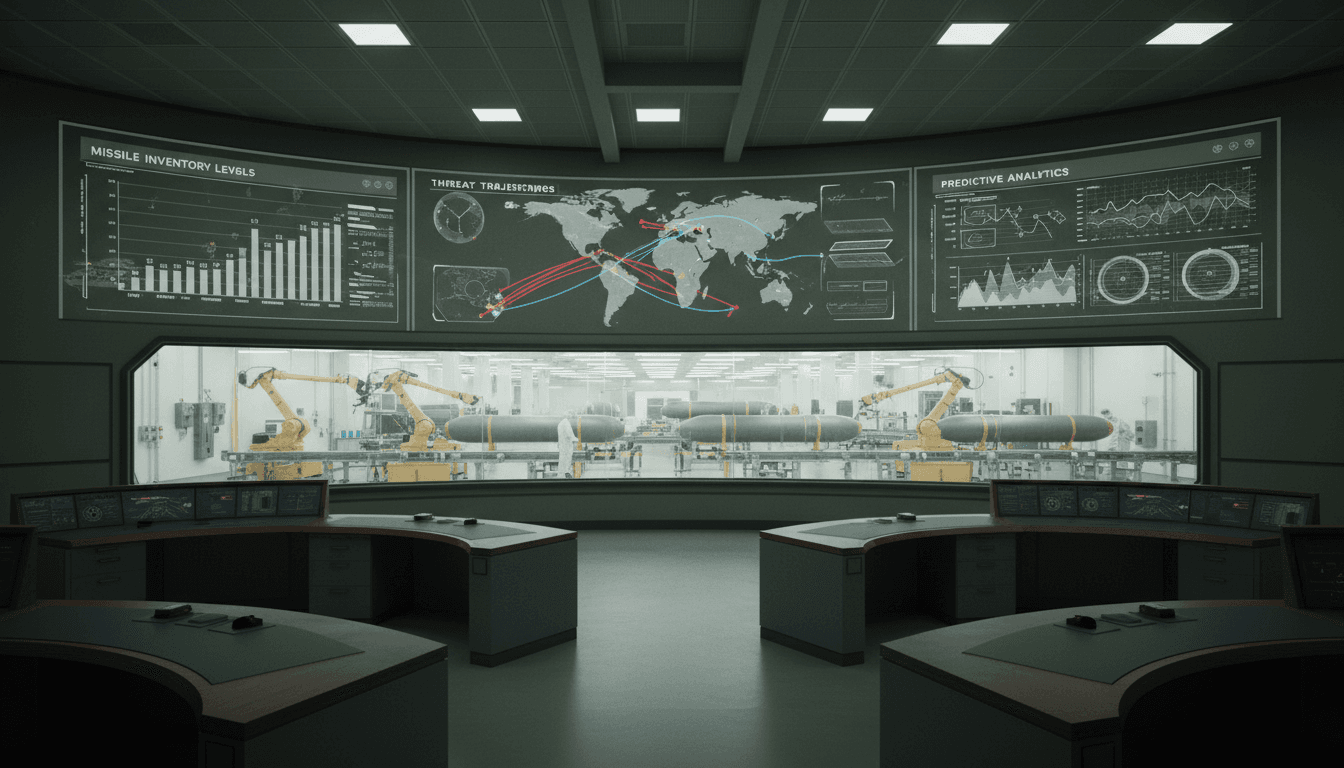

Where AI changes missile math: planning, targeting, and inventory decisions

AI in defense isn’t only about autonomy or fancy sensors. In missile warfare, the biggest near-term advantage is decision superiority: allocating limited weapons against many threats under extreme time pressure.

Three AI applications matter most for the “magazine depth” problem.

1) AI-driven simulations to stress-test war plans

If you want to know whether stockpiles are sufficient, tabletop exercises aren’t enough. You need high-volume campaign simulation that explores thousands of plausible enemy behaviors and environmental conditions.

Modern AI-enabled simulation can:

- Generate adversary “courses of action” beyond the staff’s default assumptions

- Model uncertainty (sensor errors, deception, weather, battle damage ambiguity)

- Estimate munitions consumption under different rules of engagement

This is where organizations often get surprised. They discover the plan only works if everything goes perfectly—and in real conflict, nothing does.

2) Predictive analytics for demand forecasting and replenishment

Sustaining fires is partly a forecasting problem: which theater will consume what type of missile, in what sequence, with what transportation constraints?

Predictive models can fuse:

- Training consumption patterns

- Maintenance and failure rates

- Supplier lead times

- Shipping and storage constraints

- Scenario-based operational demand

The output isn’t a single “truth.” It’s a risk-aware forecast: if conflict starts in a given window, what’s the probability you fall below minimum required stock in week 2, week 6, week 12?

For leaders, that becomes a practical decision tool: where to spend marginal dollars—inventory now, capacity expansion, or design-to-cost redesigns.

3) AI-assisted targeting and weapon-task pairing

A hidden driver of missile shortages is overkill allocation—firing premium weapons at targets that didn’t need them, or launching extra rounds because confidence is low.

AI can reduce waste by improving:

- Target classification confidence (better fusion of ISR sources)

- Weapon-to-target matching (choosing the cheapest munition that meets mission success probability)

- Shot doctrine tuning (when one round is enough vs. when two are necessary)

This doesn’t mean letting an algorithm decide lethal action. It means using AI to present commanders with clear, auditable recommendations and quantified tradeoffs.

Production at scale: the AI angle most people miss

When people say “AI in defense,” they often picture the battlefield. The larger advantage may show up inside the factory.

If new entrants can truly build missiles much faster and cheaper, they’ll do it with a blend of:

- Design-to-cost engineering (simplifying parts, reducing exotic materials, modularizing subsystems)

- Model-based systems engineering (digital threads from requirements to test)

- Automated inspection (computer vision for quality checks, anomaly detection)

- Adaptive supply chain planning (AI models that reroute and rebalance when suppliers fail)

The point isn’t buzzwords. It’s throughput.

What “orders of magnitude cheaper” must survive

Claims about dramatic cost reduction are easy to make and hard to sustain through:

- qualification testing

- environmental hardening

- safety certifications

- cybersecurity requirements

- integration with existing launch platforms and command systems

Here’s the standard I use: If a design can’t be produced with stable yield, measured quality, and predictable suppliers, it won’t close the magazine gap—even if the unit cost looks great on a slide.

The uncomfortable tradeoffs decision-makers need to own

There are real tradeoffs here, and leaders shouldn’t pretend otherwise.

Cheap munitions vs. survivability

Lower-cost missiles may have shorter range, less robust counter-countermeasures, or smaller seekers. That’s not automatically bad. It’s only bad if you ask them to do high-end jobs.

A mature force design says:

- Use expensive survivable weapons where you must.

- Use cheaper weapons where you can.

Stockpiles vs. surge capacity

Buying inventory now helps immediately. Investing in surge capacity helps later. A serious strategy usually needs both:

- Minimum viable stockpiles to avoid early failure

- Surge production plans that are contractually real, not aspirational

AI speed vs. trust and control

Faster decision cycles are useful only if commanders trust the outputs. That means:

- transparent models (or at least explainable decision logic)

- red-teaming against spoofing and data poisoning

- clear human authority in the loop

AI that can’t be audited becomes a liability under stress.

Practical steps: how to evaluate an “affordable mass” missile program

If you’re responsible for procurement, operational planning, or defense innovation, here’s a straightforward checklist I’ve found helpful.

- Define the mission slice: What targets and conditions is the missile meant for? Be specific.

- Set an exchange-ratio goal: What cost per effect is acceptable given expected threat salvos?

- Measure production realism: Can the supplier demonstrate repeatable builds and test cadence?

- Plan for training consumption: You’ll burn missiles in peacetime too. Include it.

- Bake in AI-enabled allocation: If you don’t improve targeting and pairing, you’ll waste inventory.

- Test cyber resilience: Guidance, comms, and production systems are all attack surfaces.

This is how “AI in defense & national security” becomes practical. It’s less about flashy autonomy and more about making the math work under pressure.

What this means for deterrence in 2026 and beyond

Deterrence isn’t just posture and statements. It’s the adversary’s belief that you can fight and sustain.

The builders featured in the War on the Rocks conversation are responding to a real need: missiles that can be produced in meaningful volume at lower cost. That’s encouraging. But the next step is where the U.S. will either win or stall out: connecting affordable mass to AI-driven planning, targeting discipline, and industrial throughput.

If you’re working in defense acquisition, operations, or the industrial base, the question to ask right now is blunt: Are we building a force that can afford to fire on day 30, not just day 1?