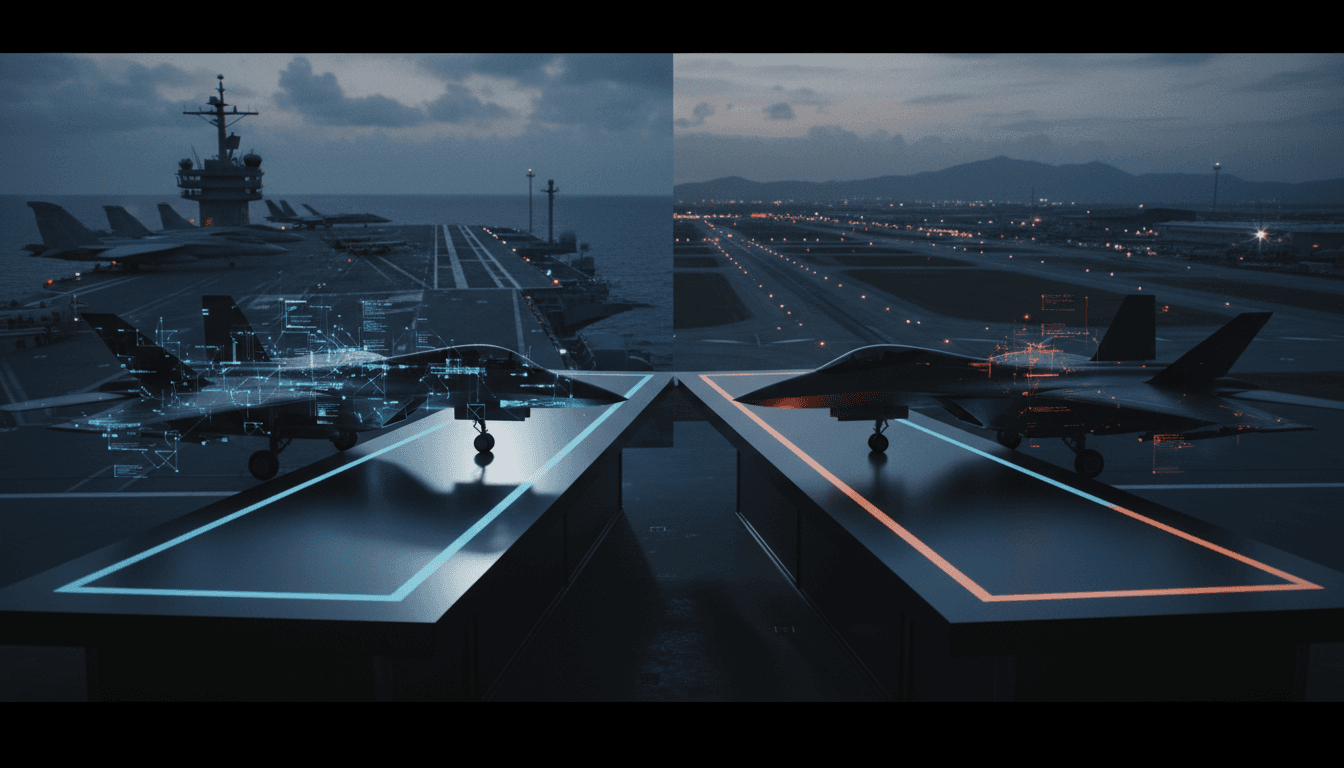

Congress funds the Air Force’s F-47 while sidelining the Navy’s F/A-XX. Here’s what that means for AI-enabled airpower and acquisition priorities.

F-47 Funded, F/A-XX Frozen: The AI Stakes for Airpower

Congress just made a loud statement about what it thinks the U.S. can build fast—and what it’s willing to keep on the shelf.

The latest version of the FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) backs the Air Force’s F-47 at roughly $2.6 billion, while giving the Navy’s next-generation fighter—commonly referred to as F/A-XX—only $74 million. That’s not “slow-rolling.” That’s keeping the program warm enough to avoid total atrophy.

For anyone tracking AI in defense and national security, this split matters for a simple reason: sixth-generation fighters aren’t just faster jets with better stealth. They’re software-defined combat systems, built around AI-enabled mission planning, sensor fusion, decision support, and human-machine teaming. When funding diverges, AI capability development diverges, too—and the downstream impact lands on everything from carrier air wings to the defense industrial base.

What the NDAA funding split really signals

The key signal is capacity: Congress is implicitly accepting the Pentagon’s view that the industrial base can’t sprint two sixth-generation programs at once.

The defense policy bill authorizes about $2.6B for the Air Force’s F-47 and $74M for the Navy’s F/A-XX. Meanwhile, separate lanes of money still exist—appropriations, reconciliation, and classified accounts. The Navy program could still get a boost (House, Senate, and reconciliation drafts have all floated substantially larger figures). But the NDAA message is clear: F-47 gets momentum; F/A-XX gets optionality.

Authorization vs. appropriations (why this isn’t fully “final”)

If you’re not living inside budget mechanics, here’s the practical takeaway: authorization sets policy and ceilings; appropriations writes the check.

So the Navy’s fighter may still see meaningful resources if appropriators insist. Recent legislative activity indicates there’s appetite to do exactly that. But even if more money arrives later, this moment still creates friction:

- Programs slow down when funding is uncertain, because contracts, staffing plans, and supplier commitments get cautious.

- AI and software teams are especially sensitive to churn, because iteration cycles depend on stable backlogs and test infrastructure.

- Carrier-specific requirements (launch/recovery, corrosion, deck handling, maintainability at sea) can’t be “bolted on later” without expensive rework.

In other words: the money can catch up, but time lost is rarely recovered cleanly.

Why this is an AI story, not just a fighter story

Next-generation aircraft are becoming flying compute nodes—part of a larger kill chain where sensors, shooters, and command elements collaborate in near-real time. AI is the glue.

If you want a crisp, citation-friendly way to think about it:

Sixth-generation fighters are procurement programs for AI-enabled combat architectures, with airframes attached.

That’s why the F-47 vs. F/A-XX split creates AI implications in three places: onboard autonomy, networked mission planning, and training.

AI-enabled sensor fusion and decision support

Modern air combat is less about “who turns tighter” and more about who understands the battlespace first—across RF, IR, EO, passive sensing, cyber-electromagnetic effects, and offboard feeds.

AI’s role here is not a Hollywood autopilot. It’s practical:

- Automated track management across cluttered environments

- Anomaly detection for low-observable threats and decoys

- Threat ranking that adapts as conditions change

- Recommendation engines for tactics, weapon pairing, and routing

The hard part isn’t inventing an algorithm. The hard part is making it:

- certifiable,

- resilient to deception,

- maintainable over decades,

- and updatable without breaking safety and mission assurance.

Stable funding determines how quickly you can build that software factory and test ecosystem.

Human-machine teaming is the real sixth-gen differentiator

Both services are chasing versions of the same future: a crewed aircraft that coordinates with uncrewed collaborative aircraft (often described as “loyal wingmen”). That coordination is an AI problem:

- Tasking and re-tasking teammates under contested comms

- Coordinating sensors without saturating bandwidth

- Sharing intent (so the human isn’t babysitting)

- Managing risk, rules of engagement, and escalation control

If the Air Force gets the first mature “combat team” concept into operational testing, it won’t just field a jet. It will field a playbook and a software stack others will be pressured to adopt.

That’s efficient—but it can also become a trap if naval aviation’s distinct realities are treated as “edge cases.”

The Navy’s problem: carrier airpower can’t be a rounding error

Here’s the stance I’ll defend: underfunding F/A-XX is a strategic risk because naval aviation is not interchangeable with land-based airpower.

Carrier air wings solve a specific operational problem: they put credible tactical airpower where the U.S. can’t (or won’t) rely on host-nation basing. That matters in the Indo-Pacific, and it matters in any scenario where access and overflight are politically constrained.

Carrier requirements change the AI and autonomy design

Carrier aviation forces different design choices that ripple into AI integration:

- Approach and landing are already precision, high-risk phases. Introducing more autonomy demands extremely rigorous verification and operational procedures.

- Deck operations are congested, dynamic, and safety-critical. Any autonomy that touches taxi, spotting, or maintenance workflows must be conservative and explainable.

- Maritime environment (salt, corrosion, humidity) punishes sensors and connectors—exactly the things AI-heavy platforms depend on.

- Contested comms over water can be brutal. If you assume persistent, high-quality data links, your “AI advantage” can disappear when it’s needed most.

So even if the Air Force’s F-47 becomes the flagship for AI-enabled air dominance, the Navy still needs its own pathway to avoid a future where the carrier air wing is operating yesterday’s software in tomorrow’s fight.

The industrial base argument is real—but it’s not the whole truth

The Pentagon’s stated logic (one sixth-gen sprint at a time) isn’t crazy. Aerospace engineering talent, specialty materials, propulsion capacity, advanced manufacturing, integration labs—these are finite.

But there’s a better framing: you can sequence airframes while parallelizing software and autonomy infrastructure.

If you starve F/A-XX to “minimum viable funding,” you risk losing:

- program continuity,

- supplier readiness,

- and, most importantly, software learning cycles.

AI-enabled defense programs improve through iteration: data collection, simulation, test, feedback, patch, repeat. Slow the loop and you slow capability.

What Congress is demanding on F-47 (and why AI teams should care)

The compromise NDAA doesn’t just hand over money. It asks for specifics: costs, schedule, basing, training, construction costs, force structure, and reserve component integration—through 2034, with a report due March 1, 2027. The F-47 is expected to first fly in 2028.

Those questions look bureaucratic, but they force a core conversation:

AI isn’t an “add-on line item”—it drives cost and schedule

If you’re building AI into next-generation combat aircraft, your critical path won’t be only tooling and flight testing. It’ll also include:

- digital engineering pipelines and model-based systems engineering,

- high-fidelity simulation environments (to generate training and test conditions),

- data rights and data labeling,

- cybersecurity and supply chain assurance for AI components,

- and continuous delivery for mission software.

If Congress wants credible cost projections through 2034, the Air Force will have to explain how it will sustain the AI stack without turning every upgrade into a multi-year re-certification ordeal.

That’s exactly the kind of operational reality the broader “AI in Defense & National Security” series focuses on: AI that ships, survives contact with adversaries, and stays supportable.

Practical takeaways: how to keep AI progress moving even with uneven funding

If you’re in government, industry, or a dual-use AI company trying to support national security outcomes, this moment suggests three pragmatic moves.

1. Build shared autonomy test infrastructure across services

Even if airframes are sequenced, autonomy shouldn’t be. The fastest path is to invest in:

- common simulation standards,

- shared red-teaming and deception testing,

- joint safety cases for autonomy,

- and portable mission autonomy modules.

If the Navy’s program is “on pause,” shared infrastructure keeps its AI ecosystem alive and reduces restart costs.

2. Treat contested comms as a design constraint, not a scenario

AI-enabled mission planning and human-machine teaming must assume:

- intermittent links,

- degraded GPS,

- spoofed tracks,

- and adversarial data.

The teams that win will be the ones shipping graceful degradation—systems that still function when the network collapses.

3. Demand measurable AI readiness metrics in program reviews

Budgets follow credibility. The easiest way for “AI features” to get cut is when they’re described vaguely.

Useful, decision-grade metrics include:

- time-to-update a model (from change request to deployable build),

- performance under deception and clutter,

- operator workload impact (measured, not claimed),

- and mission success rates in realistic simulation campaigns.

If you can’t measure it, Congress will assume it’s a science project.

What to watch in early 2026: the signals that matter

The next few months are where this story actually resolves. Watch for these indicators:

- Appropriations outcomes that either restore serious F/A-XX funding or cement the slowdown.

- Classified program activity (often reflected in subtle language shifts, not public numbers).

- Contracting actions: long-lead supplier commitments and test infrastructure awards are the real tell.

- Software factory investments tied to next-gen air dominance—because that’s where AI becomes real capability.

If you see heavy investment in test, simulation, and mission software delivery pipelines, that’s a sign the U.S. is prioritizing AI-enabled airpower as a system—not just an aircraft.

Where this fits in the “AI in Defense & National Security” series

This funding split is a clean case study in how defense priorities shape AI adoption. When Congress funds one program to move fast and keeps another on life support, it’s choosing where AI-enabled operational concepts mature first—and which mission sets will inherit them later.

If you’re building, buying, or integrating AI for national security, the smart move is to align to what remains true regardless of airframe timelines: data, simulation, autonomy verification, and resilient mission planning.

If you want to pressure-test your AI roadmap against defense acquisition reality—budgets, certification, contested environments, and human-machine teaming—this is exactly the moment to do it. The next question is blunt: will the U.S. treat AI as a shared combat capability across services, or as a feature that arrives only where the biggest check clears first?