AI-ready deterrence on the Korean Peninsula depends on faster situational awareness, coalition trust, and decision support—built for crisis tempo.

AI-Ready Deterrence on the Korean Peninsula

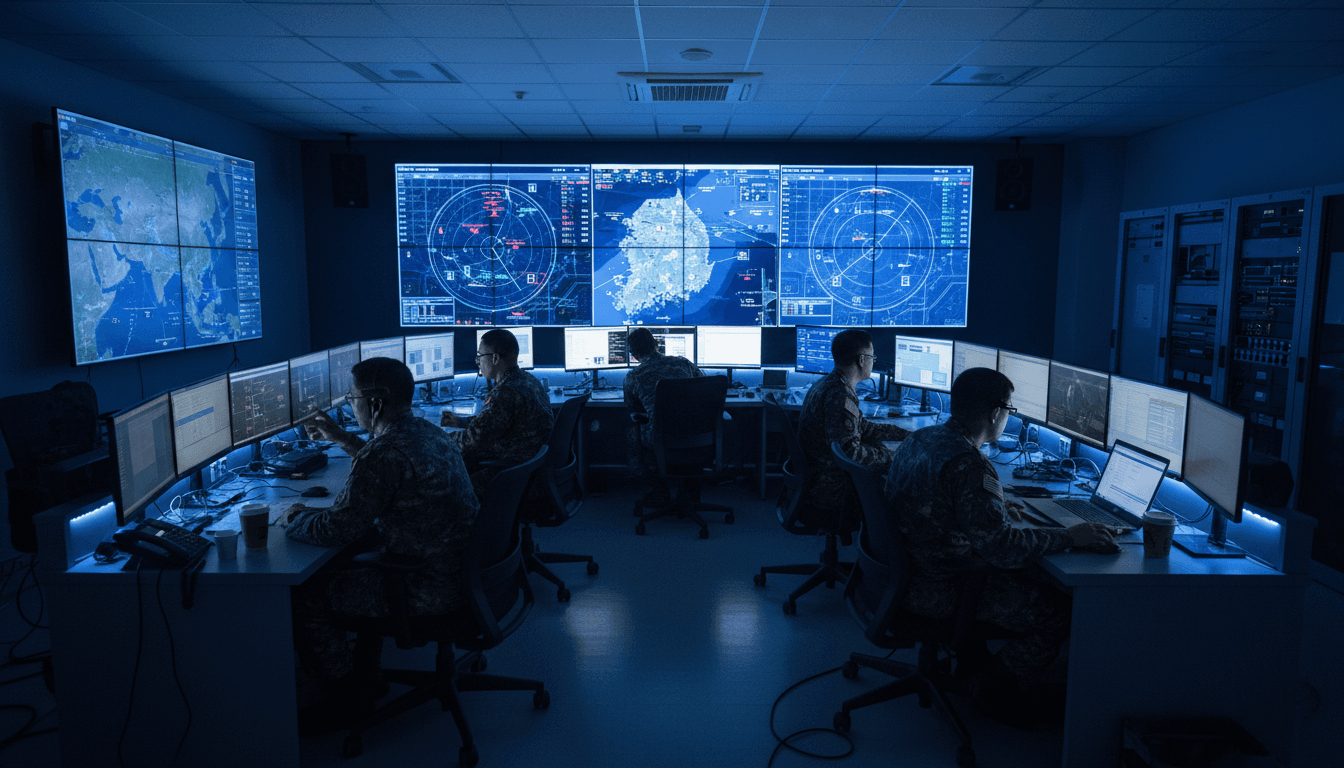

A three-star commander holding three commands—U.N. Command, the ROK–U.S. Combined Forces Command, and U.S. Forces Korea—doesn’t get to “wait for clarity.” Gen. Xavier T. Brunson’s job is built around a blunt operational standard: be ready to fight tonight. That phrase is often treated like a slogan, but on the Korean Peninsula it’s closer to a systems requirement—training calendars, stockpiles, authorities, communications pathways, joint fires, civilian evacuation plans, and alliance decision-making all have to work under stress.

Here’s what most people miss: “fight tonight” readiness is increasingly an information problem before it’s a firepower problem. The peninsula compresses timelines. It crowds sensors, people, and platforms into a tight battlespace. It adds a nuclear-armed adversary that uses deception and ambiguity as tools, not side-effects. In 2025, the question isn’t whether AI belongs in that environment—it’s how to use AI for situational awareness and decision-making without breaking trust, tempo, or control.

This post takes the leadership and readiness themes raised by Gen. Brunson’s discussion and extends them into practical guidance for defense and national security teams building AI-enabled intelligence analysis, mission planning, and deterrence architectures.

“Fight Tonight” Means Decision Advantage, Not Just Readiness

Deterrence on the peninsula works when Seoul and Washington can demonstrate credible capability, credible intent, and credible command-and-control. Capability is the visible part—exercises, deployments, munitions, air and missile defense. The less visible part is the decision engine behind it.

Gen. Brunson’s unique position—simultaneously leading U.N. Command, Combined Forces Command, and U.S. Forces Korea—highlights a reality: crisis response isn’t a single chain of command. It’s a coalition decision network with different legal authorities, rulesets, and political constraints.

AI doesn’t replace that network. It helps it function at speed.

The peninsula’s hardest constraint: time

On the Korean Peninsula, indicators and warnings can arrive late, be noisy, or be deliberately manipulated. That creates three operational pressures:

- Compression: Leaders may have hours—or less—to interpret a signal and act.

- Ambiguity: Adversary actions can look “defensive,” “routine,” or “preparatory” until they aren’t.

- Coordination burden: Every action has alliance implications; every delay compounds.

AI can help most in the part humans are worst at under stress: sifting, correlating, and prioritizing signals across domains (space, cyber, maritime, air, ground, information environment).

Deterrence fails when ambiguity outpaces decision-making.

AI for Situational Awareness: Where It Actually Helps

AI in defense and national security gets hyped as autonomy. In Korea, the near-term value is more pragmatic: better awareness for humans who must decide quickly and justify decisions across an alliance.

1) Multi-INT fusion that reduces analyst thrash

Analysts don’t suffer from a lack of data. They suffer from too much data, poorly aligned.

Applied well, AI-enabled intelligence analysis can:

- Cluster reports that reference the same unit/activity under different names

- Detect “pattern breaks” in logistics, communications, or movement

- Flag mismatches between declared exercises and observed preparations

- Prioritize anomalies by proximity, historical precedent, and confidence

The win isn’t automation for its own sake. The win is reducing cognitive load so experienced analysts spend time on interpretation, not triage.

2) Indications & warning models that are honest about uncertainty

In a crisis, leaders don’t need “certainty.” They need a clear statement of:

- What we think is happening

- Why we think it

- What would change our mind

That’s an AI design requirement as much as an analytic one.

Practical approach: produce I&W outputs as confidence-weighted hypotheses (e.g., “preparatory posture shift consistent with artillery dispersal” + top contributing indicators), rather than single-point predictions. This reduces the risk of “model theater” and supports real command judgment.

3) Computer vision for time-critical monitoring

The peninsula is heavily observed, but not all imagery is equally usable at pace. Computer vision can help by:

- Detecting new construction or revetments

- Identifying unusual vehicle density near key facilities

- Tracking movement at ports, railheads, and staging areas

The best implementations don’t pretend to be omniscient. They provide alerts, cross-cues, and audit trails, then hand off to humans.

Decision-Making in an Alliance: The Human Factors AI Must Respect

The U.S.–ROK alliance is a strategic advantage, but it adds friction when time is short. AI can either reduce that friction—or amplify it.

Shared truth is a capability

In combined commands, speed comes from shared baselines:

- Shared data definitions (what counts as an “event”)

- Shared confidence language (what “high confidence” means)

- Shared provenance (where the assessment came from)

If one side is reading a different dashboard, with different assumptions, you don’t have decision advantage—you have parallel narratives.

A practical standard I recommend: every AI-driven alert should carry three fields leaders can repeat verbatim:

- Assessment: what the system thinks is happening

- Evidence: top signals driving that assessment

- Next check: what collection/verification would confirm or refute it

That format travels well across staff shops and national boundaries.

AI must not become a trust wedge

In 2025, the adversary’s information strategy often aims to create doubt inside the alliance—about intent, about competence, about who’s escalating.

AI systems that are opaque, inconsistent, or “black box by default” create openings for internal skepticism:

- “Your model says X, ours says Y.”

- “We can’t defend this assessment publicly.”

- “We don’t know if it’s being spoofed.”

So the requirement isn’t “more AI.” It’s AI that can be explained, stress-tested, and jointly governed.

Mission Planning and Deterrence: AI as a Tempo Tool

Deterrence on the Korean Peninsula isn’t passive. It’s a continuous posture of visible preparedness. AI supports that by accelerating planning cycles while keeping humans in charge.

Faster, better courses of action (COA) development

When leaders say “fight tonight,” staff must be able to generate executable options fast:

- Which forces move first?

- What is protected vs. what is risked?

- What is the escalation logic?

- How does the plan hold if a key base is degraded?

AI can assist mission planning by rapidly exploring constraints and producing COA scaffolds—not final answers. Think:

- Route feasibility under air/missile threat

- Sustainment estimates for multiple branches

- Deconfliction of fires and airspace under congestion

- Resilience options under communications loss

A useful mental model: AI should function like an expert planner’s “second brain” that proposes, checks, and annotates—while the human team decides.

Wargaming at scale (and why it matters for Korea)

The peninsula is a scenario-rich environment: artillery saturation, cyber disruption, special operations, maritime gray-zone events, missile volleys, and coercive signaling.

AI-assisted wargaming can help commands test:

- Branches and sequels at realistic tempo

- Logistics fragility (fuel, munitions, spares)

- Civil-military coordination points

- Decision thresholds (what triggers which response)

The payoff is deterrence credibility. Plans that have been stress-tested are faster to execute, easier to explain, and harder for an adversary to exploit.

Guardrails: The Risks That Matter Most in a Korea Scenario

AI in defense and national security fails in predictable ways. On the Korean Peninsula, those failures have outsized consequences.

1) False positives that drive escalation

If an AI system over-alerts, it can push leaders toward unnecessary posture changes that look escalatory. The fix isn’t “turn it off.” The fix is:

- Calibrated thresholds tied to actionability

- Human adjudication gates for high-impact alerts

- Continuous evaluation against red-team deception

2) Data poisoning and spoofing

Adversaries will try to shape what sensors see and what models learn. Treat model integrity as operational readiness:

- Segmented training pipelines

- Provenance tracking for data sources

- Deception-aware validation sets

- Rapid rollback and “known good” baselines

3) Overconfidence from clean dashboards

A crisp interface can hide messy reality. Leaders should demand that AI outputs include:

- Confidence bands

- Missing data flags

- Competing hypotheses

If the model can’t tell you what it doesn’t know, it’s not ready for crisis use.

4) Governance that can’t survive a crisis

The worst time to argue about authorities is during the event. Combined commands need pre-set governance for:

- Who can tune models and thresholds

- Who can approve operational use cases

- How audit logs are maintained and shared

- How to handle model disagreements across partners

A Practical Readiness Checklist for AI-Enabled Commands

If you’re building AI capabilities for a volatile region like the Korean Peninsula, aim for operational usefulness, not lab performance.

- Define “decision products” first. What must a commander decide in the first 30 minutes, 2 hours, 12 hours?

- Instrument provenance end-to-end. Every alert should be traceable to data, model version, and assumptions.

- Design for coalition use. Shared confidence language and repeatable brief formats matter as much as accuracy.

- Run deception drills. Train the model—and the humans—against spoofing, masking, and narrative manipulation.

- Measure outcomes, not novelty. Track time-to-assessment, analyst workload, and decision cycle time, not just AUC scores.

The metric that matters in crisis is time saved without trust lost.

Where This Leaves Military Leadership

Gen. Brunson’s “fight tonight” posture underscores something timeless: deterrence is personal. It’s leaders making hard calls with incomplete information, while managing alliance relationships and signaling to adversaries.

AI strengthens that leadership when it improves situational awareness, mission planning, and decision support—and when it’s built with the humility to show uncertainty. The goal isn’t autonomous warfighting. The goal is decision advantage that holds up under pressure.

If your organization is exploring AI in defense and national security, the Korean Peninsula is a useful stress test. The timelines are short, the sensing is dense, and the consequences of misread signals are high. Systems that work there tend to work anywhere.

What would you change in your AI decision-support stack if you knew you had to brief a combined commander—clearly, defensibly, and fast—tonight?