AI counter-drone defense is shifting from expensive missiles to scalable, networked systems. Here’s what the Army’s Flytrap demo reveals—and how to evaluate it.

AI Counter-Drone Defense at Scale: What Flytrap Proves

A $4 million missile shouldn’t be the default answer to a $20,000 drone. Yet that’s been the uncomfortable math for many air defense units—and it’s exactly the kind of math Russia’s drone-heavy playbook is designed to exploit.

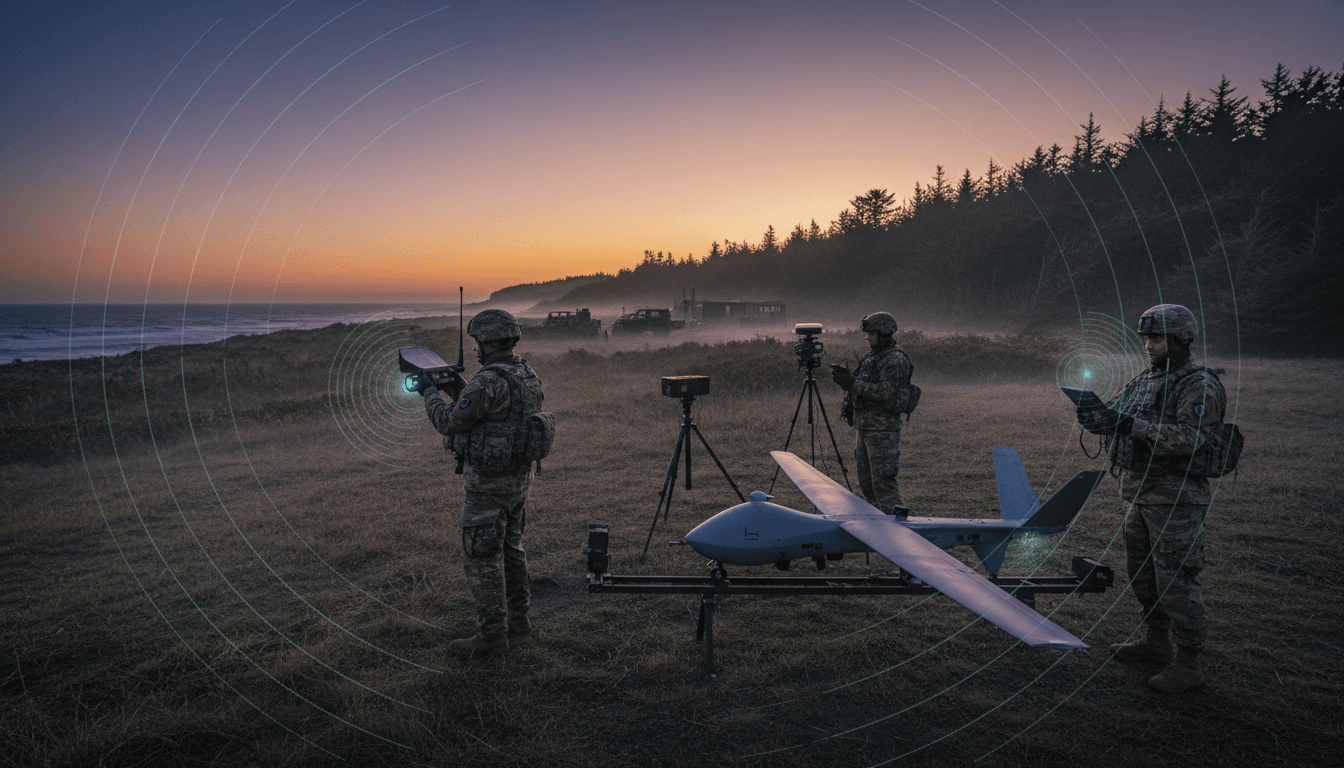

In northern Germany this November, the U.S. Army ran a live demonstration that quietly signaled a shift: counter-drone warfare is starting to look scalable. Not perfect. Not solved. But closer. Project Flytrap showed how you can stand up a layered defensive network in days, fuse multiple sensor feeds in real time, and push usable targeting data to everyone from a rifleman to a commander.

For this AI in Defense & National Security series, Flytrap is a useful lens because it highlights what AI is actually good for in modern defense: not “magic autonomy,” but decision advantage, sensor fusion, cost control, and faster fielding cycles.

Counter-drone warfare at scale is a data problem first

Counter-drone defense fails when detection, tracking, and identification don’t keep up with drone quantity, variety, and tactics. The hard truth is that the “shooter” isn’t the bottleneck in many cases—the targeting-quality data pipeline is.

Project Flytrap’s most meaningful story isn’t a single gadget. It’s the networked approach: multiple sensors, multiple effectors, and a common operational picture that can be shared across classification boundaries without bogging down into minutes of latency.

The threat has shifted from “drone” to “drone ecosystem”

Modern drone threats aren’t one platform. They’re an ecosystem:

- Cheap, expendable FPV drones used like guided grenades

- Larger ISR drones feeding artillery and long-range fires

- Autonomous or semi-autonomous drones that don’t care if you jam GPS

- Swarms and massed raids designed to saturate human attention and traditional air defense queues

That ecosystem forces a new requirement: you must detect and classify fast enough to decide what matters and what doesn’t, in real time.

Why AI belongs in the middle of the kill chain

AI’s best role in counter-UAS isn’t “press button, drone disappears.” It’s the middle layers:

- Sensor fusion: correlating tracks across radar, EO/IR, RF detection, passive sensing, and acoustic cues

- Track quality scoring: estimating confidence, velocity, heading, and intent cues

- Classification and prioritization: distinguishing a quadcopter near a perimeter from a coordinated FPV run at a critical node

- Decision support: recommending effectors based on cost, safety, and probability of kill

Put simply: AI turns noise into a queue you can fight from.

Flytrap’s key lesson: integration beats individual brilliance

A counter-drone program that treats each sensor and effector as a standalone product is going to disappoint you. What Flytrap demonstrated is that you can take a mixed set of capabilities and make them cooperate—quickly—if you design for interoperability and speed of deployment.

The Army’s demonstration included everything from net-shooting interceptors to specialized rifles and .50-caliber machine guns. That variety matters because no single countermeasure works everywhere:

- Kinetic fire can be effective but demands good cues and training.

- Jamming can work, until the drone is autonomous or frequency-agile.

- Nets can be ideal near civilians, but not always at range or against speed.

- Lasers are promising, but still constrained by power, weather, and fielding timelines.

“Right side of the cost curve” is the whole point

Here’s the stance I’ll defend: cost curve is a strategy, not a budget detail.

Flytrap’s message—echoed by senior air defense leadership on site—was that defense has to win economically as well as tactically. If the attacker can spend a tenth and force you to spend ten times, they can keep pressure on indefinitely.

A scalable counter-drone stack aims for:

- Low-cost sensing at scale (including distributed “every soldier is a sensor” concepts)

- Low-cost effectors for the majority of targets (bullets, nets, cheaper interceptors)

- High-end intercept only when justified (cruise missiles, larger UAS, or high-confidence threats)

AI supports that economics by improving first-shot correctness and reducing “wasteful engagements” driven by uncertainty.

Real-time data sharing (with no latency) is a force multiplier

One of the most operationally relevant claims coming out of Flytrap was real-time sensor integration with no latency and the ability to share to:

- Units operating classified systems

- Units operating sensitive but unclassified systems

- Front-line shooters who need a cue right now

That last point is where AI-enabled command and control becomes more than a buzzword. If your sensor fusion engine can push a drone’s probable track and intercept window to a rifleman, you’ve changed the game—because you’ve scaled “good enough” targeting to the edge.

The AI-enabled counter-UAS stack: what “scale” actually requires

Counter-drone warfare at scale means repeatable performance under saturation. That requires a stack, not a point solution.

1) A layered sensing mesh (active + passive)

Scale starts with detection coverage and track continuity. Flytrap highlighted integration between active radar and passive radar approaches (passive detection that infers objects through disturbances in existing radio signals).

Why this matters:

- Active radars can be targeted, jammed, or forced into unfavorable emission control.

- Passive methods can fill gaps, complicate adversary planning, and reduce single points of failure.

AI’s contribution here is correlation: matching partial observations into a coherent track, then maintaining it despite intermittent detections.

2) Edge-level identification and targeting assistance

It’s easy to underestimate how hard it is to hit a small drone with a rifle under stress.

Aim-assist systems—like those demonstrated for rifle engagements—are a practical example of “AI at the edge.” They don’t need to be sentient. They need to do three things well:

- Stabilize and predict motion

- Provide an actionable lead cue

- Reduce time-to-hit for average shooters

In my experience reviewing these systems, the make-or-break issue is rarely algorithm accuracy in a lab. It’s training integration, rules of engagement, and whether the UI works in gloves, cold, and chaos.

3) Multiple effectors matched to mission context

A scalable defense doesn’t pick one effector. It builds a menu and applies policy:

- Urban / civilian proximity: nets and controlled kinetic options

- Perimeter defense: kinetic fire, mobile interceptors

- Base defense / critical infrastructure: layered interceptors, higher-end sensors, and automated cueing

AI can recommend which effector to use, but humans must encode constraints: collateral risk, airspace coordination, and escalation rules.

4) A command-and-control layer that survives classification reality

A common failure mode in defense AI programs is ignoring classification boundaries until the end.

Flytrap’s emphasis on sharing data across different security contexts is the “boring” part that actually determines whether the system scales. If the best track lives only in a classified enclave, the rifleman never sees it—and the defense collapses to whoever can see the drone with their naked eye.

Rapid procurement is part of the technology story

Scale isn’t just “buy more.” It’s field faster, iterate faster, and retire losers quickly.

Project Flytrap’s structure—hundreds of applicants, a subset selected, and hands-on soldier feedback—reflects a procurement truth: counter-UAS is evolving too quickly for slow, monolithic programs.

Here’s a practical model defense organizations are moving toward:

- Short competitive cycles (weeks/months, not years)

- Live demos with instrumented results (range data, misses, false alarms, response time)

- Soldier-centered usability scoring (setup time, battery logistics, training burden)

- Modular contracting so you can swap components without rewriting the whole architecture

This is also where AI can help indirectly: instrumentation data from exercises can be turned into improvement loops—better models, better cueing logic, better threat libraries.

What leaders should demand before buying “AI counter-drone” systems

If you’re responsible for acquisition, base security, operational planning, or integration, you’ll save yourself pain by insisting on specific answers.

A practical evaluation checklist

Demand clarity on these items—before a pilot becomes a dependency:

- Detection and false alarm rates by environment (urban clutter, coastal, forest, snow)

- Time-to-cue at the edge (seconds matter more than perfect tracks)

- Performance under saturation (10 drones isn’t “scale”; 50+ begins to be interesting)

- Resilience to jamming and emission control

- Data rights and model update process (how threat libraries update, who controls them)

- Interoperability with existing radios, C2, and airspace management

- Cybersecurity posture (especially for systems that ingest RF or connect to mission networks)

A line I use internally: If the vendor can’t explain how it fails, they don’t understand it well enough to deploy it.

Where this goes next for AI in Defense & National Security

Flytrap points toward a near-future reality: counter-drone defense will look less like a single “air defense weapon” and more like a continuously learning, distributed system. Sensors will be cheap and everywhere. Effectors will be mixed. AI will sit in the glue layer, turning scattered detections into decisions.

Over the next 12–24 months, the most important progress won’t be flashy autonomy demos. It will be:

- Better sensor fusion with lower compute and power needs

- Faster deployment packages that units can set up in days

- More robust identification that reduces accidental engagements

- Practical edge tools that help average soldiers perform like specialists

If you’re building or buying in this space, focus on one metric: cost-per-protected-hour under real threat conditions. That’s how you’ll know whether your counter-drone system actually scales.

If you want help evaluating counter-UAS architectures, AI sensor fusion options, or what “good” looks like in an operational pilot, that’s exactly the kind of work this series is meant to support. What part of the stack is your biggest blocker right now—sensing coverage, integration, or engagement authority?