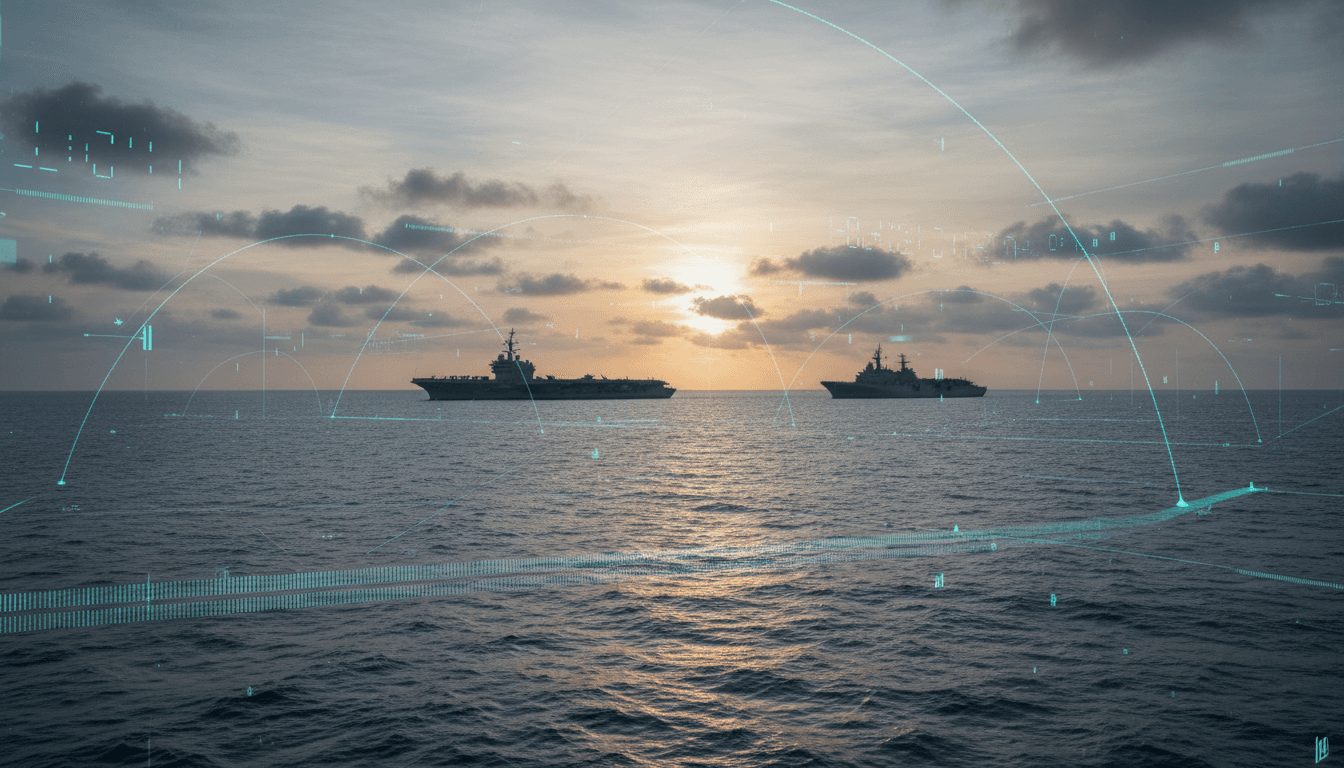

China’s navy is growing fast. Here’s how AI-driven ISR, predictive analytics, autonomy, and cyber defense can help the U.S. and allies keep decision advantage.

AI’s Playbook for China’s Rapid Naval Expansion

China didn’t just add ships this year—it added options.

In November 2025, Beijing commissioned the 80,000-ton Fujian, its first aircraft carrier with electromagnetic catapults, and signaled the near-term arrival of the Sichuan, a major amphibious assault ship designed around helicopters and large combat drones. Pair that with China’s shipbuilding scale—about 50% of global ship output versus under 1% for the U.S.—and you get a strategic reality that’s hard to talk around: mass and speed are becoming their own form of capability.

For leaders working in defense, national security, and the industrial base, the naval story isn’t only about hulls, missiles, and flight decks. It’s about decision cycles—who detects, understands, and acts first. That’s where AI belongs in the conversation. If China’s advantage is production capacity and tempo, then the U.S. and partners need an edge in intelligence, surveillance, predictive analytics, autonomous systems, and cyber resilience—the parts of modern deterrence that scale with software.

China’s “world-class navy” isn’t hype—it's a systems problem

China’s naval buildup matters because it combines quantity, modernity, and industrial depth in a way that changes wartime math.

Open-source assessments commonly describe a PLAN force of 370-ish battle force ships and submarines within a broader ecosystem of 1,000+ vessels (including auxiliaries and coast guard). The number that should keep planners up at night isn’t only how many ships exist today—it’s the replacement rate China can plausibly sustain if a conflict drags on.

The Fujian and Sichuan: two ships, two messages

The Fujian signals a leap in carrier operations. Electromagnetic catapults aren’t just a prestige feature; they translate into:

- Higher sortie generation potential

- Greater flexibility in aircraft types (including heavier fixed-wing platforms)

- A clearer pathway to mature carrier air wings

The Sichuan signals something different: it points toward drone-centric maritime assault and distributed aviation. Amphibious ships aren’t headline-grabbing in the way carriers are, but in a Taiwan scenario, they’re closer to the center of gravity—moving troops, staging helicopters, and increasingly acting as floating launch pads for unmanned aircraft.

If you’re watching for what changes the regional security equation, the amphibious and missile ecosystem is usually the bigger story.

Why the industrial base is the real strategic weapon

A navy is the visible end of a supply chain. China’s shipyards sit behind the PLAN like a second fleet.

When a country can build commercial ships at scale and convert workforce, yards, logistics, and suppliers to military priorities, it gains a wartime advantage that doesn’t show up on peacetime order-of-battle charts. That’s why U.S. and allied leaders keep circling back to shipbuilding capacity as the uncomfortable foundation of maritime power.

AI can’t weld steel. But it can change how quickly democracies choose and coordinate the investments that matter.

The balance of power is shifting from platforms to decision advantage

A common mistake is treating naval competition as a contest of “who has better ships.” The more accurate frame is: who can create a reliable picture of reality and act on it faster—at scale and under attack.

That’s a decision advantage problem, and AI is now a core ingredient.

AI-powered ISR: turning noise into early warning

China’s naval activity generates enormous volumes of observable signals—satellite imagery, AIS patterns (including spoofing and going dark), port activity, emissions, social media traces, procurement hints, and exercise rhythms.

Modern AI in intelligence work isn’t about replacing analysts. It’s about building pipelines that:

- Detect shipyard and port changes from imagery (new hull sections, dry dock cadence, pier expansion)

- Track unit patterns across time (which ships deploy together, readiness cycles, replenishment behavior)

- Fuse multi-source signals into a confidence-scored assessment

The practical goal: reduce the time between “something changed” and “decision-makers understand why it matters.”

Done well, AI-driven ISR also helps allies coordinate. Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and others don’t need identical fleets to contribute meaningfully—they need shared awareness and interoperable analysis outputs.

Predictive analytics: forecasting deployments and coercion windows

Naval coercion often sits below the threshold of war: presence patrols, maritime militia pressure, exercises timed to political events, and “routine” transits that are anything but routine.

Predictive analytics can support deterrence by forecasting:

- Likely deployment windows based on maintenance and training cycles

- Probable exercise escalation pathways after incidents at sea

- Replenishment and logistics footprints (the tell for sustained operations)

A useful mindset here is “hurricane tracking for fleets.” You don’t predict exact landfall weeks out, but you can narrow cones of uncertainty and pre-position options.

Autonomous systems: the cost-imposing counterweight

If China can out-build in traditional ship categories, the counter is to raise the marginal cost of aggression without matching hull for hull.

That’s where autonomous and semi-autonomous systems matter:

- Unmanned surface vessels for sensing, decoys, and picket duty

- Unmanned underwater vehicles for surveillance and mine countermeasures

- Attritable aerial systems for maritime strike support and ISR

The strategic benefit is not “robots win wars.” It’s that autonomy enables mass without crew risk, and it forces an adversary to spend scarce missiles and attention on cheap targets.

In a maritime fight, attention is a resource. Autonomy can drain it.

AI and cyber: naval expansion widens the attack surface

As fleets modernize, they become more software-defined—and more targetable.

A bigger PLAN means more:

- Networked command-and-control nodes

- SATCOM dependencies

- Supply chain complexity

- Industrial control systems in shipyards and depots

That’s a larger digital surface area for espionage and sabotage on all sides. From a U.S. and allied perspective, the AI angle is straightforward: AI-driven threat detection and anomaly hunting is one of the few approaches that scales with the volume and speed of modern cyber operations.

What “AI-driven cyber defense” should mean in practice

The phrase gets abused, so here’s what I look for when teams claim they’re applying AI to cybersecurity in defense environments:

- Behavior-based detection that catches novel tactics (not only signature matching)

- Entity resolution across networks, users, endpoints, and OT systems

- Automated triage that reduces analyst fatigue and false positives

- Resilience playbooks that assume degraded communications and contested space

If you can’t operate under disruption, you don’t have deterrence—you have theater.

What the U.S. and allies should do next (the non-glamorous list)

The fastest way to lose this competition is to treat AI as a tech demo and shipbuilding as someone else’s problem.

Here are actions that actually map to the threat:

1) Build “maritime intelligence data products,” not one-off dashboards

ISR organizations often end up with beautiful interfaces and fragile pipelines. The better approach is to define reusable products:

- A continuously updated order of battle with confidence scoring

- Port and shipyard activity indices (weekly cadence)

- Logistics and replenishment network models

- Deployment pattern forecasts tied to uncertainty ranges

These products should be exportable to allies in formats they can use, even if they don’t share every data source.

2) Prioritize compute, labeling, and governance as warfighting enablers

Most AI programs fail on basics:

- Not enough labeled training data

- Data rights and classification friction

- Models that can’t be audited or explained to commanders

For defense AI, governance isn’t bureaucracy—it’s what makes a model deployable. If a commander can’t understand when a system fails, they won’t rely on it.

3) Treat autonomy as a fleet design principle

Autonomy shouldn’t live in a special office. It should shape procurement:

- Requirements that assume contested comms

- Mission packages designed for manned-unmanned teaming

- Sustainment plans for attritable systems (spares, rapid replacement, simple maintenance)

If systems can’t be replaced quickly, they won’t deliver the cost-imposing logic autonomy promises.

4) Make shipbuilding analytics part of deterrence

Shipyard output is a strategic signal. AI can support national policy by monitoring:

- Yard expansion and modernization

- Supplier bottlenecks and surge indicators

- Dual-use production patterns

That kind of visibility helps leaders decide when to invest, when to partner with allied yards, and when to use economic tools. It also makes bluffing harder.

5) Stress-test the AI stack like it’s going to be attacked (because it will)

If your maritime AI system can’t handle:

- Data poisoning attempts

- Deception (spoofing, decoys, camouflage)

- Sensor outages

- Sudden distribution shifts (new ship classes, new tactics)

…then it’s a fair-weather tool. The Indo-Pacific is not a fair-weather environment.

Where this fits in the “AI in Defense & National Security” series

This series keeps returning to a simple idea: AI matters most when it compresses the time from signal to decision to action.

China’s naval expansion is a perfect case study because it pressures every layer at once—industrial capacity, regional deterrence, operational readiness, cyber resilience, and allied coordination. The ships are visible. The real contest is the invisible layer: sensing, fusion, prediction, autonomy, and secure command-and-control.

If you’re responsible for strategy, acquisition, or operational planning, the question isn’t whether China has a world-class navy. It’s whether your organization has built a world-class decision system to keep pace.

What would change in your posture if you could reliably forecast PLAN deployments 30 days out—and prove your confidence interval to a commander?