Ultra-low-power reservoir computing enables fast edge AI for smart meters and grid sensors—cutting latency, bandwidth, and cloud costs.

Low-Power Reservoir AI for Smarter Grid-Edge Analytics

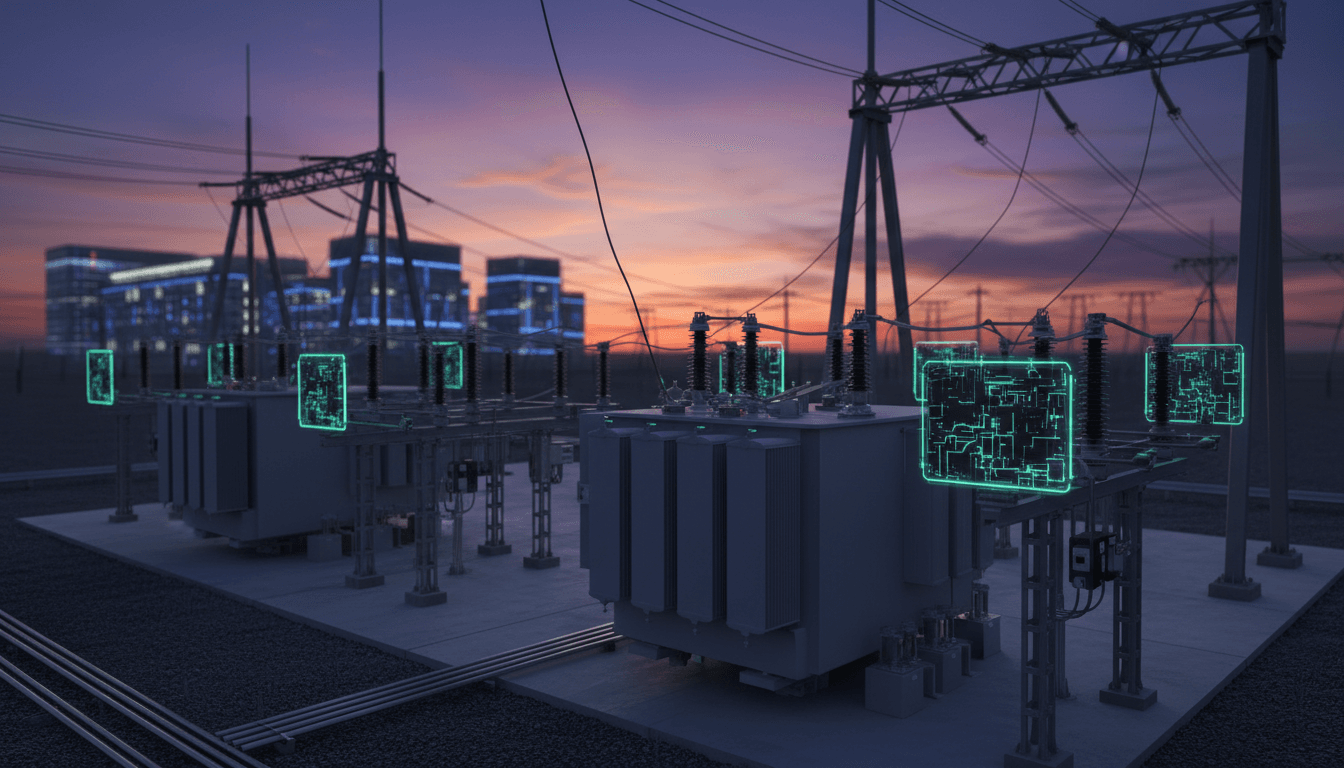

A surprising number of “AI in energy” projects fail for a boring reason: they assume there’s a data center nearby. In the real world, your analytics often live at the grid edge—inside a smart meter, on a pole-top sensor, in a substation cabinet, or embedded in a battery container where power, cooling, and connectivity are limited.

That’s why a recent demo from a Japanese team (Hokkaido University working with TDK) is more than a clever party trick. They built an analog reservoir-computing chip that can predict the next step in a time series fast enough to beat a human at rock-paper-scissors—in real time—while consuming about 80 microwatts total (four cores, 20 µW per core). Those numbers matter.

For our AI in Cloud Computing & Data Centers series, this is a useful counterpoint: the future of infrastructure AI isn’t only “bigger models in bigger clusters.” A lot of value will come from tiny models running close to the physical world, taking pressure off networks and reducing the amount of raw data we ship back to the cloud.

Why ultra-low-power edge AI matters to energy & utilities

Answer first: Utilities need edge AI because the grid is becoming faster, more variable, and harder to observe with centralized analytics alone.

Between renewables, electrification, and increasingly dynamic loads, grid behavior can change on second-by-second timescales. If your sensor has to stream raw waveforms or high-rate telemetry to the cloud before it can detect an anomaly, you’ve already lost time—and you’ve increased cost.

Here’s what I’ve seen work in practice: treat the cloud as the coordination layer (model governance, fleet updates, long-horizon planning), and treat the edge as the reflex layer (fast detection, immediate control hints, data triage).

Ultra-low-power chips change the economics of that reflex layer. They can enable:

- Always-on monitoring without frequent battery swaps

- Lower bandwidth (send features and events, not raw streams)

- Lower latency (detect locally; escalate only when needed)

- Better privacy and resilience (useful for customer-side devices)

If you’re building energy analytics, this is the difference between “cool pilot” and “deployable at scale.”

Reservoir computing in plain terms (and why it fits time-series)

Answer first: Reservoir computing is a neural approach that’s unusually well-matched to time-series prediction because it bakes “memory” into the network dynamics and trains only a small output layer.

Traditional deep learning often relies on training many layers and adjusting lots of weights (commonly with backpropagation). That can be powerful, but it’s expensive in compute and energy—especially if you need on-device learning or rapid adaptation.

Reservoir computing flips the setup:

- You have a fixed “reservoir”: a network with loops and rich internal dynamics.

- Inputs excite that reservoir, producing a high-dimensional internal state.

- You train only the readout layer (the final mapping from reservoir state to output).

A useful way to think about it: the reservoir acts like a complex set of filters and echoes that turn the recent past into a distinctive “signature.” Then the readout learns how to interpret that signature.

Why utilities should care: a huge chunk of grid intelligence is time-series work.

- Load ramps

- Frequency and voltage excursions

- Harmonic patterns

- Motor starts and switching events

- Battery degradation signals

- Thermal drift and seasonal baselines

Reservoir computing isn’t the right tool for every ML task, but it’s often a strong fit when the world you’re modeling is dynamic, noisy, and sometimes chaotic.

What’s new here: an analog reservoir chip with microwatt power

Answer first: The key technical step is putting the reservoir into an analog CMOS circuit, so inference happens through physics-like dynamics rather than power-hungry digital multiply-accumulates.

The team implemented artificial “neurons” as analog circuit nodes made from:

- a nonlinear resistor

- a memory element based on MOS capacitors

- a buffer amplifier

Their prototype includes four cores, each with 121 nodes, and uses a “simple cycle reservoir” where nodes connect in one big loop. That loop still provides the feedback and state richness reservoir computing needs, without the wiring explosion of arbitrary connections.

And then the headline numbers:

- ~20 µW per core

- ~80 µW total

The demo that caught attention was rock-paper-scissors prediction using a thumb motion sensor. The interesting part isn’t the game—it’s what it implies: low latency time-series prediction on-device, fast enough to respond within a human reaction window.

From an energy perspective, that “respond now, not later” capability is where edge AI earns its keep.

Why analog matters (even if you’re a software-first team)

Analog compute can feel like “someone else’s problem,” but you’ll feel its impact in product constraints:

- Smaller batteries (or longer life)

- Less heat in sealed enclosures

- More sensors per device (because the compute budget is tiny)

- More frequent inference (higher sampling rates become feasible)

For grid-edge deployments—especially retrofit sensors—those are the constraints that determine whether you get a fleet of 50 devices or 50,000.

Energy & utility use cases that map cleanly to reservoir AI

Answer first: Reservoir AI is most compelling in utilities when you need fast, local prediction from streaming data and you can’t afford cloud latency or continuous uplink.

Below are practical matches where a low-power time-series predictor can pull real weight.

1) Smart meters that don’t just measure— they interpret

Smart meters already capture interval data; some capture higher-rate signatures for power quality. The bottleneck is turning that stream into actionable intelligence without sending everything upstream.

A reservoir-style edge model can:

- detect abnormal load shapes (stuck relays, failing compressors)

- flag non-technical losses patterns (where policy permits)

- identify power quality events (sags, swells) and classify them locally

The payoff for cloud and data centers: fewer raw uploads, more targeted incident packets, and better dataset curation for retraining.

2) Substation and feeder monitoring with “event-first” telemetry

Most utilities don’t want to store endless waveform data. They want the waveform when something happens.

A low-power predictor can run continuously and trigger:

- event capture windows (pre-fault and post-fault)

- anomaly metadata creation (features + confidence)

- prioritized backhaul during constrained comms

This aligns with a modern cloud pattern: edge filtering + cloud correlation.

3) Battery energy storage systems (BESS) and inverter-rich sites

As grids become more inverter-dominated, fast transients and control interactions matter more. Local prediction can support:

- early-warning signals for thermal runaway precursors (as part of a layered safety system)

- detection of control instability signatures

- local estimation helpers that reduce reliance on continuous cloud connectivity

Even when “the cloud is the brain,” BESS sites need fast local nervous systems.

4) Predictive maintenance where power is scarce

Some of the best predictive maintenance opportunities are on assets that are inconvenient to power: remote valves, cathodic protection stations, rural line sensors.

Microwatt-class inference makes it realistic to place intelligence on:

- vibration and acoustic sensors

- motor current signature monitors

- transformer bushing monitors

How this changes the cloud/data center story (not replaces it)

Answer first: Low-power edge AI doesn’t compete with the cloud—it changes what the cloud is responsible for.

If inference and short-horizon prediction happen at the edge, cloud and data center workloads shift toward:

- fleet learning (training on curated edge-selected events)

- model governance (versioning, rollback, compliance)

- asset-level digital threads (tying edge events to CMMS, SCADA, GIS)

- long-horizon forecasting (days to seasons)

- simulation and planning (hosting what-if scenarios)

The result is often lower cost and better reliability: you don’t need to overbuild backhaul or store mountains of data “just in case.”

A stance I’m comfortable taking: utilities that keep treating edge devices as dumb collectors will pay a permanent tax in cloud spend, bandwidth, and operational lag. Intelligence has to move closer to the measurement point.

Practical adoption checklist for utilities and vendors

Answer first: To evaluate a low-power edge AI approach, focus less on “model accuracy” in a lab and more on deployment realities: latency, drift, maintainability, and integration.

Here’s a pragmatic checklist I’d use.

What to validate in pilots

-

Latency budget

- What’s the maximum time from signal capture to decision?

- Does the device meet it under worst-case conditions?

-

Energy budget

- Battery life under real sampling and inference rates

- Idle power vs always-on power

-

Drift behavior

- Seasonal drift, sensor aging, recalibration requirements

- How often do you need retraining or re-baselining?

-

“Edge selectivity” quality

- Are you capturing the right events, or flooding the cloud with noise?

- False positives cost real money in truck rolls and analyst time.

-

Integration path

- How do events land in your historian / data lake?

- Can SCADA/ADMS workflows consume them?

Where reservoir computing is a good fit

- streaming signals with strong temporal dependence

- need for local inference under tight power constraints

- limited or expensive connectivity

Where it’s probably not the best fit

- tasks needing heavy spatial reasoning (e.g., imagery)

- use cases requiring large context windows without clever state design

- problems where you must learn deep feature hierarchies end-to-end

What to watch in 2026: from demos to deployable silicon

Answer first: The biggest question isn’t whether reservoir chips can predict time-series—it’s whether they can be packaged, validated, and supported like utility-grade components.

A rock-paper-scissors demo proves low-latency prediction and on-device learning potential. For utilities, the next hurdles are more operational:

- temperature stability across outdoor ranges

- long-term calibration drift

- security and firmware update models

- manufacturability and yield

- standard interfaces into edge gateways

If vendors clear those hurdles, a microwatt-class predictor becomes a new building block for grid-edge architectures.

The interesting long-term outcome: cloud workloads become “higher value per byte.” Instead of collecting everything, you collect what matters—because the edge is smart enough to decide.

Next steps if you’re building grid-edge AI

If you’re a utility, an OEM, or a cloud provider selling into energy, I’d start with one concrete move: pick a single time-series problem where latency or bandwidth is currently painful, and design an edge-first pipeline for it.

- Define the local decision that needs to happen within seconds.

- Define the “receipt” that needs to land in the cloud (event + features + context).

- Define the retraining loop and who owns it.

This post is part of our AI in Cloud Computing & Data Centers series because the cloud is still the coordination layer—but the grid edge is where physics happens. A chip that can do useful prediction at 80 µW is a reminder that infrastructure AI is becoming a full-stack problem, from silicon all the way up to cloud governance.

Where in your energy data stack are you still shipping raw signals because the edge can’t think yet—and what would change if it could?