Hydrogen for data centers is moving from pilot to procurement. Here’s what the Vema–Verne deal means for utilities, AI-driven dispatch, and grid planning.

Hydrogen for Data Centers: What Utilities Must Plan Now

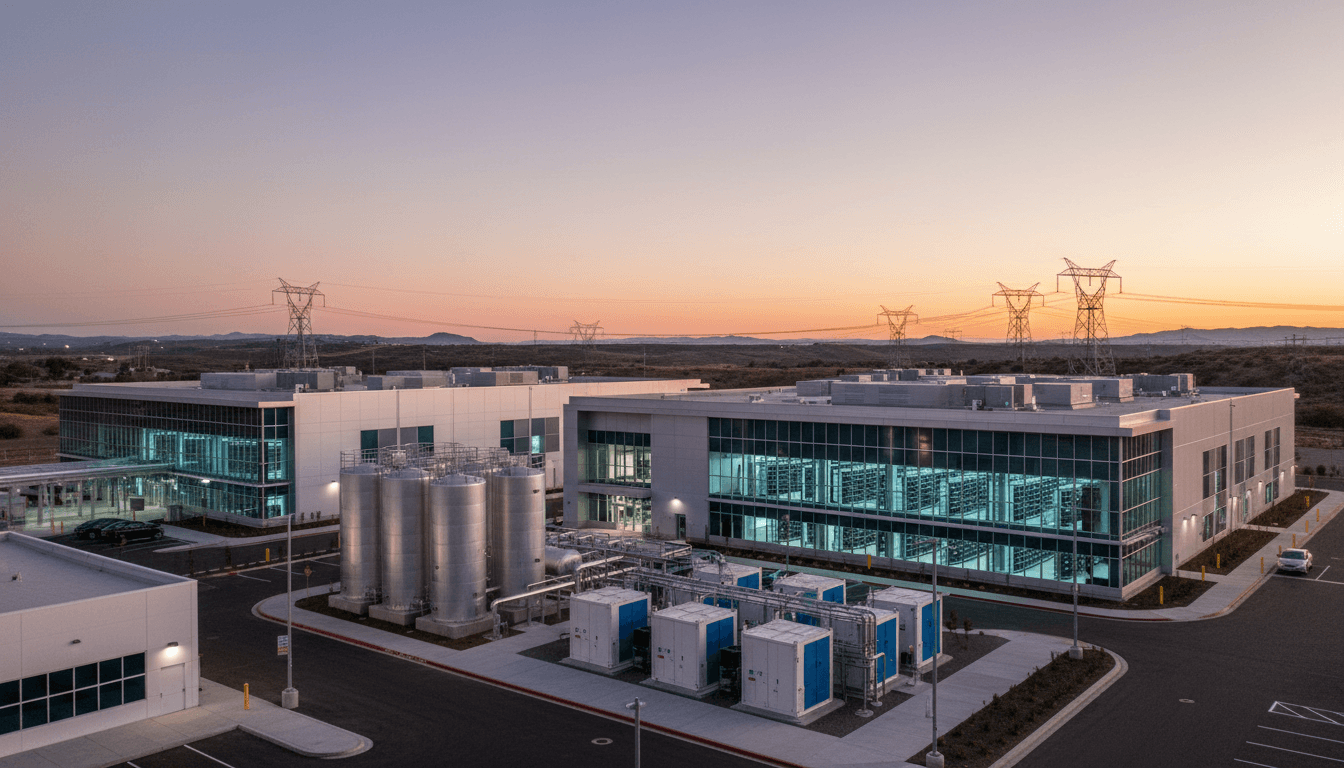

California’s data center power problem isn’t theoretical anymore. A single AI training cluster can pull tens of megawatts, and new campuses are being scoped at 100–500 MW blocks—loads that look more like aluminum smelters than “IT buildings.” Against that backdrop, a notable development landed this week: Vema Hydrogen signed a 10-year hydrogen purchase and sale agreement with Verne, a provider of on-site power and cooling for data centers, with operations targeted as early as 2028 and production scaling to 36,000 metric tons per year.

Most headlines will file this under “clean energy for data centers.” I think it’s bigger than that. This is a signal that the data center sector is moving from buying renewable attributes to buying firm molecules and dispatchable power architectures—and utilities will either help orchestrate that transition or spend the next decade managing interconnection queues, local constraints, and political blowback.

This post is part of our AI in Cloud Computing & Data Centers series, so we’ll stay focused on what matters operationally: how hydrogen-powered data center infrastructure changes grid planning, and where AI-driven energy management fits when you’re coordinating on-site generation, emissions requirements, heat management, and reliability.

The Vema–Verne deal is really about “firm power”

Answer first: Data centers aren’t chasing hydrogen because it’s trendy—they’re chasing it because they need firm, scalable, low-emission power that can be built on timelines the grid often can’t match.

The agreement pairs Vema’s “Engineered Mineral Hydrogen (EMH)” supply with Verne’s on-site power and cooling approach. The companies point to a key driver: data center electricity consumption is expected to double by 2030, with the sector seeking roughly 945 TWh of energy (as cited by the companies involved).

Here’s what I’ve found in conversations with both hyperscalers and regulated utilities: the debate has shifted from “Can we procure enough renewables?” to “How do we keep the lights on 24/7 while we wait for transmission upgrades and gas constraints to clear?” Hydrogen shows up in that second question.

Why 2028 matters more than it sounds

A 2028 start date is a planning siren. Most utilities can’t deliver hundreds of megawatts of new capacity at a constrained node in three years without painful tradeoffs. So large customers are increasingly building parallel power plans:

- Grid supply where it’s available

- On-site generation for near-term certainty

- A longer-term pathway to lower emissions and lower risk of curtailment

Hydrogen—whether produced from electrolyzers, biogenic pathways, or emerging geologic/mineral routes—fits as an input fuel for firm generation. Even when hydrogen isn’t the cheapest kWh, it’s often the cheapest schedule certainty.

Hydrogen-backed on-site power changes the utility relationship

Answer first: Once a data center can self-supply meaningful load, the utility’s role shifts from “energy provider” to “system orchestrator,” and the winners will be the utilities that operationalize that shift.

On-site hydrogen power for data centers can take different forms (fuel cells, hydrogen-capable turbines/reciprocating engines, blended systems), but the grid-facing implications are similar:

- Load becomes more elastic. The site can choose when to import, when to island, and when to export (if allowed).

- Interconnection requirements get more complex. Protection, controls, and fault contribution look different with inverter-based resources, engines, or fuel cells.

- Planning assumptions break. A “500 MW new load” might actually behave like 500 MW at peak and 50 MW off-peak, depending on fuel availability, price signals, and dispatch strategy.

Utilities that treat these sites like classic, steady loads will get burned. The better approach is to treat them like hybrid customers: part load, part generator, part flexibility resource.

The reliability math: hydrogen is a capacity story

Data centers buy reliability in layers: grid feeds, UPS/batteries, generators, and increasingly alternative firm fuels. Hydrogen is attractive because it can support long-duration operation when batteries can’t, without relying on diesel runtime exceptions.

But reliability depends on more than the prime mover. It depends on:

- Fuel storage and delivery constraints

- Safety systems and permitting

- Redundancy strategy (N+1, 2N, distributed blocks)

- Controls that decide when to run on-site vs import

That last bullet is where AI earns its keep.

Where AI actually fits: dispatch, cooling, and constraint management

Answer first: AI is most valuable when it coordinates decisions across power, cooling, and fuel—because optimizing one domain in isolation usually raises cost or risk in another.

In the AI in Cloud Computing & Data Centers world, “AI for efficiency” often gets reduced to server utilization. That’s only half the story. The big operational wins come from facility-level intelligence that treats the data center as an energy system.

1) AI-driven dispatch for hybrid power portfolios

A hydrogen-enabled campus can look like a microgrid with multiple objectives:

- Minimize cost ($/MWh + demand charges + fuel)

- Maintain reliability (ride-through, islanding readiness)

- Meet emissions targets (hourly matching, NOx limits, carbon accounting)

- Protect equipment life (runtime limits, cycling penalties)

Rule-based controls struggle once you add real-world volatility: CAISO price swings, curtailment events, heat waves, and fuel logistics. AI-based optimization can handle multi-variable tradeoffs—especially when paired with constraint-aware solvers.

Practical example (decision loop):

- Forecast next 48 hours: IT load, ambient temperature, grid price, grid curtailment probability, hydrogen inventory burn rate.

- Select dispatch plan: import baseline, run hydrogen units during peak price hours, keep reserves for contingency.

- Validate constraints: permit limits, ramp rates, maintenance windows, minimum fuel reserve.

- Execute and re-optimize every 5–15 minutes.

This is where utilities can partner instead of resist: offer telemetry, constraints, and event signals so the site’s AI can behave like a good grid citizen.

2) Cooling optimization becomes a power strategy

Hydrogen and on-site generation don’t remove the cooling problem—they make it more intertwined.

Cooling can be 20–40% of facility electricity use depending on climate and design. When you add on-site generation, you also introduce:

- Waste heat opportunities (or liabilities)

- New operating constraints during high ambient conditions

- Potential combined heat and power thinking (even if not traditional CHP)

AI can optimize cooling with a broader objective function: not just the lowest PUE, but the best system outcome (cost + reliability + emissions).

3) Utility-side AI: forecasting flexible import behavior

Utilities need AI too. If large data center campuses become partially self-supplying, net load forecasting must incorporate:

- Customer dispatch signals (price response, DR events)

- Fuel availability risk (hydrogen delivery disruptions)

- Probability of islanding during contingencies

A utility that can’t predict whether a campus will import 400 MW or 80 MW at 6 p.m. is planning blind.

The hard parts: economics, permitting, and “clean” claims

Answer first: Hydrogen for data centers will scale only if projects are credible on three fronts: delivered cost, permitting/safety, and verifiable emissions performance.

The Vema–Verne announcement includes a strong stance: power that’s “not dependent on state or federal incentives.” That’s a compelling claim, and it points to a broader truth: data centers don’t want their long-term reliability plan to hinge on policy cycles.

Still, three practical questions show up in every serious hydrogen conversation.

What does “low-emission” mean in operations?

Data centers are moving toward hourly carbon accounting and more scrutiny on local pollutants. Even if hydrogen is low-carbon, the on-site generation technology matters:

- Fuel cells can offer very low local emissions

- Combustion-based systems may require stringent NOx controls

If you’re a utility or energy provider, don’t let “hydrogen” be the end of the conversation. Make it the start of a measurable emissions plan.

Can it get permitted at speed in California?

Hydrogen introduces new safety and permitting needs: storage, setbacks, detection, venting, and emergency response coordination. If operations are targeted for 2028, permitting pathways and AHJ alignment need to start early.

A practical stance: projects that treat permitting as a late-stage checkbox will slip. Projects that run parallel workstreams (engineering + permitting + community engagement) have a real chance.

Is the fuel supply bankable and predictable?

Hydrogen-backed reliability is only as good as the supply chain. The deal’s stated scale—36,000 metric tons per year—implies a serious production and delivery plan.

For customers and utilities assessing similar deals, the bankability checklist should include:

- Volume guarantees and ramp schedule

- Quality specs and contaminant limits

- Delivery mode and redundancy

- Force majeure language (and what happens during disruptions)

A practical playbook for utilities and energy providers (next 90 days)

Answer first: The near-term win is to get ahead of hydrogen-enabled data center growth with better interconnection design, data-sharing, and operational coordination.

If you support large load growth (or regulate it), here are concrete steps that pay off quickly:

- Create a “hybrid campus” interconnection pathway. Treat sites with on-site generation and flexible import as a standard class, not a one-off.

- Define telemetry and controllability requirements up front. If the campus can island, you need visibility—real-time power flows, unit status, and intent signals.

- Offer tariff options that reward predictability. Time-varying rates, capacity commitments, and flexible interconnection agreements can reduce system risk.

- Co-design demand response that respects data center reliability. Don’t pitch generic curtailment. Pitch structured programs with verified baselines, clear notice windows, and compensation that matches the value.

- Use AI to anticipate transformer- and feeder-level constraints. Hydrogen doesn’t eliminate local distribution bottlenecks; it changes when and how they bind.

These moves aren’t flashy, but they prevent the worst outcome: adversarial relationships where customers self-build behind the meter and the grid loses both revenue stability and operational visibility.

What this signals for 2026 planning cycles

Hydrogen for data centers is becoming a real procurement category, not a pilot science project. The Vema–Verne agreement is one more step toward a future where large compute loads behave like dispatchable energy hubs—part consumer, part producer, part flexibility provider.

In our AI in Cloud Computing & Data Centers series, the recurring theme is that AI isn’t just adding load; it’s forcing better infrastructure decisions. Hydrogen partnerships are one of those decisions. When paired with AI-driven energy management, they can reduce grid stress, improve resilience, and create new coordination models between utilities and customers.

If you’re a utility, an energy provider, or a data center developer, the question to answer before next year’s capital plan isn’t “Will hydrogen win?” It’s this: Are you building the controls, contracts, and operating model that make hybrid power campuses safe and predictable for the grid?

The sites that scale fastest won’t be the ones with the fanciest fuel. They’ll be the ones that can prove reliability, emissions performance, and grid behavior—hour by hour.

Want help scoping an AI + hydrogen operations strategy?

If you’re evaluating hydrogen-enabled on-site power for a data center—or you’re a utility trying to plan around large, flexible campuses—start with an operational model, not a technology brochure.

Bring these three inputs to the first workshop:

- A 12–24 month load ramp forecast (with confidence bands)

- A one-line diagram showing intended interconnection and islanding modes

- A control objective list (cost, reliability, emissions, and constraints)

From there, you can decide where AI optimization belongs, what data you’ll need, and what contractual commitments keep everyone honest.