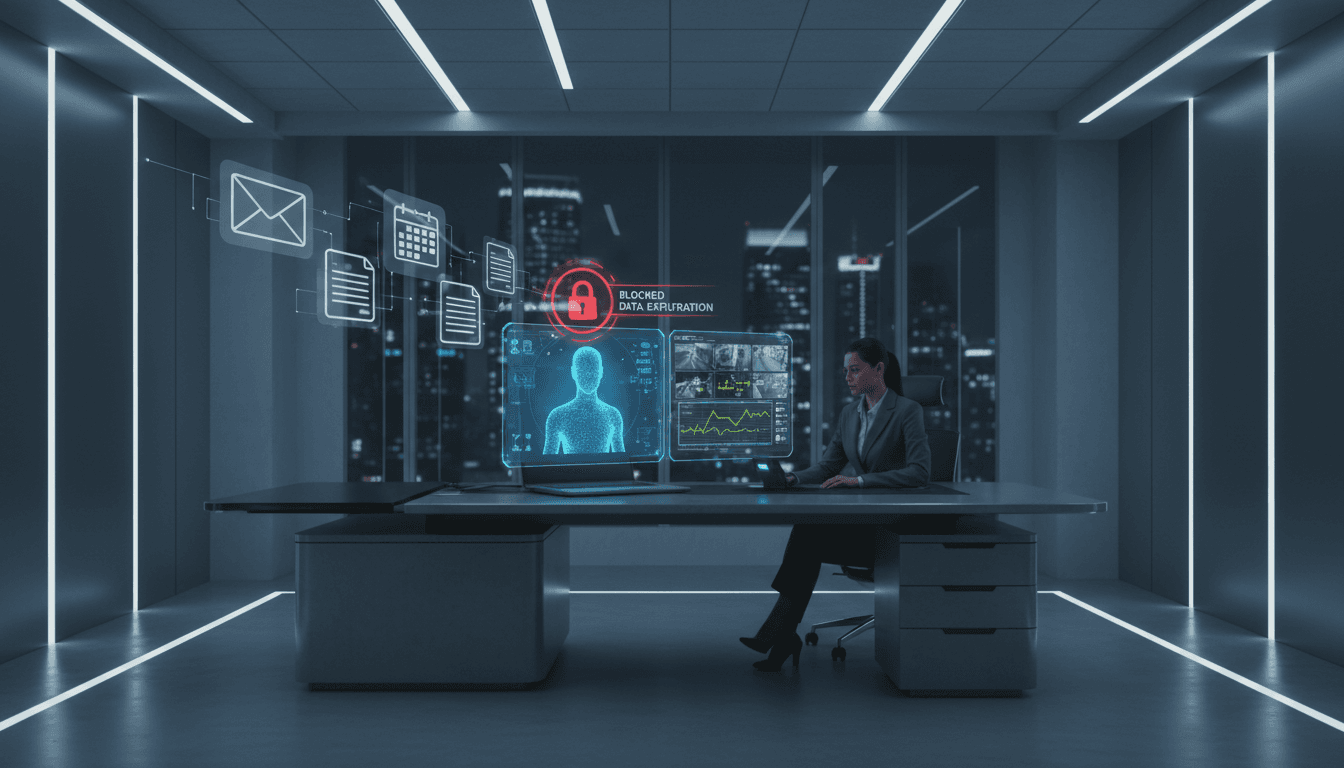

GeminiJack showed how no-click prompt injection can exfiltrate data through enterprise AI assistants. Learn practical guardrails and AI-driven detections to prevent leaks.

No-Click Prompt Injection: Lessons from GeminiJack

Most companies still treat their AI assistant like a helpful app. GeminiJack proved it should be treated like infrastructure—the kind that can quietly read your mail, your docs, your calendar, and then hand your secrets to an attacker.

Earlier this month, researchers disclosed a critical no-click vulnerability in Gemini Enterprise that enabled data exfiltration by planting hidden instructions inside everyday Workspace artifacts (Docs, Gmail, Calendar invites). The employee didn’t have to open a file, click a link, or approve anything. The “interaction” was just normal work: asking the assistant to find something.

Google has fixed the issue. The bigger lesson remains: any RAG-based enterprise assistant with broad connectors is a new access layer—and therefore a new attack surface. If you’re deploying AI across corporate content in 2026 planning cycles, this is the moment to set guardrails that actually hold up in production.

What GeminiJack teaches us about enterprise AI risk

GeminiJack is a clean example of why “we restricted chat” isn’t a security strategy. The risk didn’t come from an employee oversharing in a conversation; it came from the assistant retrieving poisoned context.

Here’s the core security shift: when an AI assistant can retrieve from Gmail, Docs, Calendar, and shared drives, it becomes a meta-user that can access whatever the requesting user can access—sometimes more efficiently than the user can.

That matters because attackers don’t need to compromise an endpoint to create impact. They can:

- Influence what the assistant reads (by inserting instructions into content)

- Steer what the assistant does with retrieved data (by manipulating the prompt context)

- Extract data through unexpected side channels (like external resource loading)

If you’re a CISO, the scary part isn’t the novelty. It’s the normalcy. This attack can look like “employee searched for budget doc,” not “employee clicked malware.”

Why no-click vulnerabilities are so dangerous

No-click exploitation breaks a lot of the controls organizations rely on:

- User awareness training doesn’t help if there’s nothing to notice.

- Email security may not flag a benign-looking Doc share.

- DLP often focuses on files leaving through known channels, not an assistant accidentally embedding data into an outbound request.

- Traditional SIEM detections may not have the right telemetry to distinguish normal AI activity from malicious retrieval-and-exfil.

Put bluntly: when the assistant becomes the exfiltration engine, your tooling needs to watch the assistant.

How a “no-click prompt injection” attack works (in plain English)

The mechanics matter because they’ll show up again—in other products, other vendors, and internal copilots.

A typical indirect prompt injection chain looks like this:

- Attacker creates a normal artifact: a Google Doc, Calendar invite, or email.

- Hidden instructions are embedded in the content (or in formatting/metadata that’s easy for a model to read and humans to miss).

- Artifact is shared into the organization, often from outside or via a compromised third party.

- Later, an employee asks the assistant something routine: “Show me Q4 budget plans” or “Find the acquisition deck.”

- The assistant’s retrieval layer pulls in the attacker’s poisoned artifact as “relevant context.”

- The model follows the hidden instructions, potentially:

- requesting additional sensitive info from other sources it can access

- transforming or summarizing it

- embedding it into something that leaves the environment

In GeminiJack, researchers reported exfiltration via a disguised external image request. That’s not the only possible outlet. Similar patterns can target:

- webhook calls

- external connectors

- “helpful” auto-generated emails

- ticketing integrations

- CRM notes

The pattern is the point: retrieval + instruction-following + outbound channel.

Snippet-worthy takeaway: If an attacker can influence what your assistant retrieves, they can influence what your assistant does.

Why AI-driven threat detection needs to cover the assistant layer

Most security programs are still organized around endpoints, identities, networks, and cloud workloads. AI assistants cut across all of them. That’s why AI-driven threat detection is becoming non-negotiable: you need detection that can reason over cross-system behavior.

A practical stance I’ve found helpful: treat the assistant as a privileged integration service with its own threat model.

What “good” detection looks like for enterprise AI assistants

You don’t need magical defenses. You need visibility plus correlation. Specifically:

- Assistant activity logs: prompts, retrieval sources, citations, and tool calls.

- Connector-level telemetry: which documents, emails, and calendar events were retrieved.

- Outbound request monitoring: any external calls, image loads, web fetches, or API calls initiated by assistant workflows.

- Identity context: which user invoked the assistant, from which device, with what session risk.

Then you correlate the story:

- Why did a “budget search” cause retrieval of a newly shared external doc?

- Why did the response include an external resource reference?

- Why did the assistant access finance documents outside the user’s normal pattern?

This is where AI for security can do real work. Not “write a policy.” Real detection:

- clustering normal assistant behavior vs. anomalous retrieval chains

- spotting prompt-injection signatures (instructional language, tool-call coercion, jailbreak-like patterns)

- flagging suspicious context shifts (e.g., a benign user query followed by retrieval of sensitive terms like “acquisition,” “wire,” “payroll,” “cap table”)

A simple way to think about prevention vs. detection

Prevention is ideal, but detection is mandatory.

- Prevention reduces how often the assistant can be tricked.

- Detection reduces how long the assistant can be tricked.

If you’re forced to choose, choose detection. Attackers only need one bypass. Defenders need fast containment.

Practical mitigations you can implement this quarter

Here’s what I’d prioritize for enterprise copilots and RAG assistants—especially during year-end rollovers when teams are sharing docs, onboarding contractors, and exchanging plans.

1) Reduce connector blast radius (least privilege for AI)

Treat assistant connectors like service accounts with a strict scope.

- Limit which drives/mailboxes/calendars the assistant can search.

- Separate “general productivity” from “finance/legal/HR” corpora.

- Create tiered retrieval: public/internal content first; sensitive content only when explicitly required.

A good internal metric: percentage of corporate content reachable by the assistant for an average employee. If that number is “most of it,” you’re betting your security on prompt hygiene.

2) Add retrieval and tool-use guardrails that are enforceable

A policy that says “don’t follow hidden instructions” is not a control.

Controls that actually help:

- Block or heavily restrict external fetches (including image loads) from assistant outputs.

- Require explicit user confirmation for tool actions: sending emails, posting messages, creating tickets.

- Sanitize retrieved content to strip hidden markup, comments, and suspicious instruction patterns before it reaches the model context.

3) Instrument the RAG pipeline like a production service

You want an audit trail with enough detail to investigate quickly:

- user query

- documents retrieved (IDs, owners, share source)

- ranking scores (why each doc was pulled)

- final prompt context (or a secure hash of it)

- tool calls/outbound requests

If you can’t answer “what did the model see?” you can’t do incident response on assistant-driven data exposure.

4) Deploy AI-specific detections in your SOC

Add detections that map to real abuse paths:

- Retrieval includes a newly shared external doc + sensitive query terms

- Assistant output contains external URLs/resources when the user didn’t ask for them

- Sudden spikes in assistant queries for finance/legal terms from atypical users

- Assistant accesses high-sensitivity docs outside business hours or from risky sessions

If you already do UEBA, extend it to assistant behavior analytics. It’s the same idea, just a new actor.

5) Red-team the assistant using your real content patterns

Tabletop exercises don’t expose these issues. Adversarial testing does.

Run controlled scenarios that simulate:

- poisoned Doc shares from external domains

- “helpful” meeting invites with embedded instructions

- prompt-injection strings hidden in white text, comments, or footnotes

Measure outcomes:

- Did the assistant retrieve the poisoned artifact?

- Did it follow the instructions?

- What data could have left the environment?

- Would your logging have caught it within 15 minutes?

That 15-minute target is a solid operational benchmark for assistant-driven exfiltration. If you can’t detect within a quarter hour, you’re relying on luck.

The hidden cost of enterprise AI: a new security control plane

Enterprise AI is often sold as “productivity with existing permissions.” That framing is incomplete.

What you’re really buying is a new control plane that:

- reads across systems at machine speed

- makes decisions on retrieved content

- outputs data into channels users trust

That’s powerful. It’s also fragile if you don’t secure the retrieval layer, the instruction-following layer, and the outbound layer as one system.

Google’s fix (including architectural separation between components) is a reminder that some problems aren’t configuration mistakes—they’re design-level problems. When a product changes architecture to reduce risk, you should ask: Do we have similar coupling in our own AI stack?

That includes internal copilots built on:

- vector databases + embeddings

- document ingestion pipelines

- plugin/tool frameworks

- “search + summarize” workflows

If your assistant can read broadly and act quietly, you need controls that assume an attacker will try to hide inside “normal behavior.” Because they will.

What to do next if you run a corporate AI assistant

Start with a short, opinionated plan:

- Inventory every data connector and tool call your assistant can use.

- Cut scope for sensitive domains (finance, legal, HR) until you have hard guardrails.

- Block outbound resource loading by default in assistant responses.

- Turn on assistant logging that supports incident response, not just analytics.

- Deploy detections for poisoned retrieval + anomalous outbound behavior.

If you only do one thing: treat assistant telemetry as first-class security telemetry. The organizations that win with enterprise AI won’t be the ones with the most copilots. They’ll be the ones that can prove, quickly, when a copilot did something unsafe.

Where does this go next? As more teams adopt agentic workflows—assistants that don’t just answer but also act—the question will shift from “can the model leak data?” to “can the model execute a business process on attacker-influenced context?”