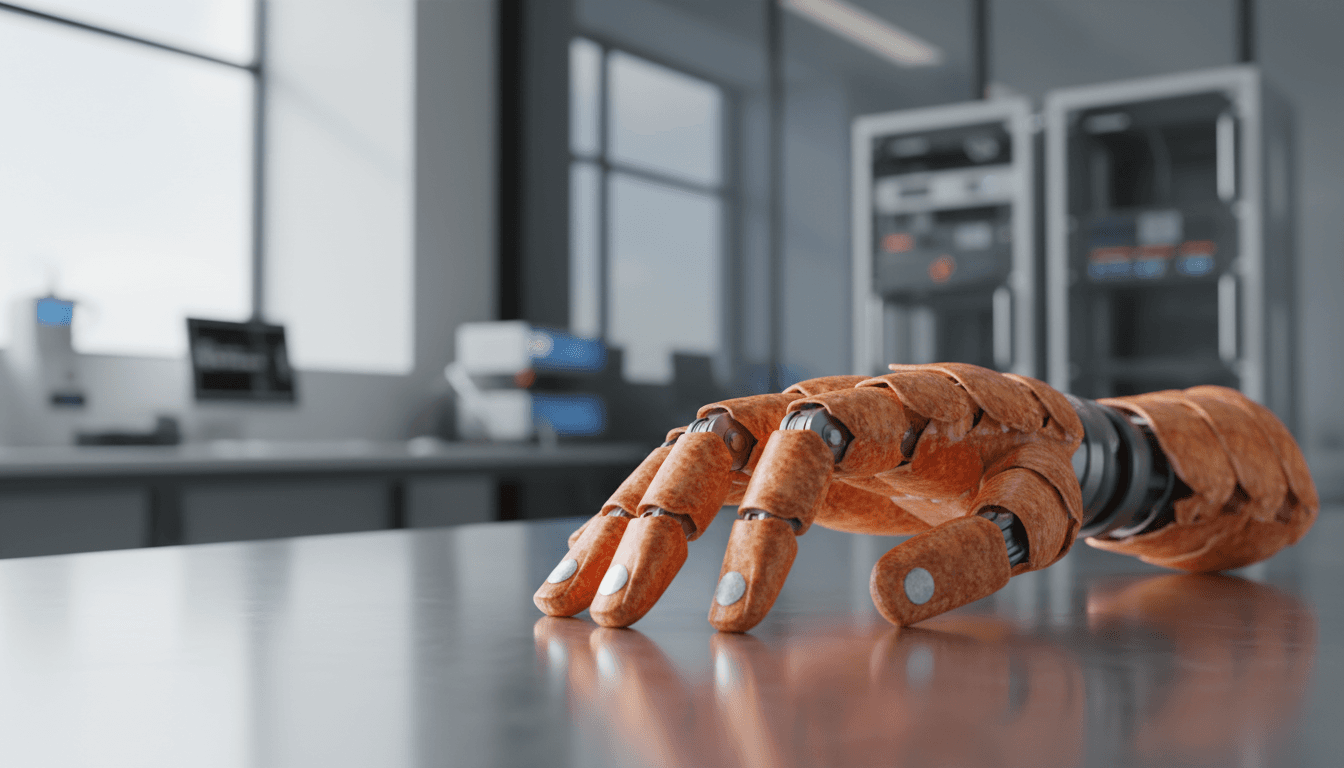

Bio-derived robotic hands using lobster-shell materials need AI control to stay precise. See where sustainable, compliant fingers fit in real automation.

Lobster-Shell Robotic Hands: Sustainable AI Dexterity

A modern robotic hand is a small miracle of engineering—and a small nightmare of materials. Traditional designs stack aluminum, rare-earth magnets, petroleum-based plastics, adhesives, and silicone skins into a device that’s hard to recycle and expensive to repair. Meanwhile, the global seafood industry generates millions of tons of shell waste each year, much of it destined for landfill or low-value use.

That’s why the idea behind a bio-derived robotic hand that uses lobster shells for fingers hits a nerve. It’s not just a quirky lab headline. It’s a practical signal that robotics is starting to care about what happens after deployment: end-of-life handling, supply-chain resilience, and whether we can build dexterous automation without piling up more hard-to-dispose composites.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: sustainable materials won’t matter in robotics unless AI control makes them perform. Bio-based structures can be lighter, safer, and cheaper—but they’re also variable. AI is the part that turns “variable” into “adaptable.”

Why lobster shells belong in a robotic hand

Answer first: Lobster shells are an underused, high-volume waste stream rich in chitin, a structural polymer that can be processed into strong, lightweight biocomposites suitable for compliant robotic fingers.

Shells from lobsters, crabs, and shrimp are mostly chitin, proteins, and calcium carbonate. When researchers extract and process chitin (or its more process-friendly derivative, chitosan), they can form films, fibers, foams, and composites. In robotics, that’s attractive because hands benefit from materials that are:

- Compliant (they deform a bit instead of shattering)

- Lightweight (lower inertia improves control and reduces motor size)

- High friction (better grip with less squeezing force)

- Potentially biodegradable or easier to recycle compared to mixed plastics and silicones

From “biomimicry” to “bio-derived”: the important shift

Biomimicry usually means copying nature’s shapes—like tendon routing inspired by human anatomy. Bio-derived means something more operational: using nature-based feedstocks in the bill of materials.

That’s a big deal for automation teams. The reality is that materials drive maintenance schedules and spare-part logistics as much as mechanics do. If your grippers crack, your line stops. If your spare fingers take six weeks to source, your ROI slides.

A bio-derived finger made from processed shell material can be designed for fast swap and local fabrication, which is exactly the sort of unglamorous detail that makes automation succeed.

The “use everything” mindset maps to manufacturing economics

The RSS snippet’s point—don’t waste animal parts—translates neatly to factories: waste is a design flaw that shows up later as cost. In 2025, with tighter ESG reporting and increasing scrutiny on supply chains, even mid-sized manufacturers are being pushed to quantify waste streams.

Bio-derived components give you a credible story and a plausible cost strategy:

- turn waste into usable polymer feedstock

- reduce reliance on volatile petrochemical inputs

- simplify disposal and potentially reduce hazardous waste handling

The hard part: bio-based materials are inconsistent—and that’s where AI wins

Answer first: Bio-derived robotics succeeds when AI compensates for material variability through sensing, calibration, and adaptive control.

Shell-derived composites aren’t as uniform as injection-molded commodity plastics. Their properties can shift with:

- source species and diet

- processing chemistry and moisture content

- fiber alignment or filler ratio

- aging and repeated loading cycles

If you try to control a lobster-shell finger like a rigid aluminum linkage, you’ll fight it. If you treat it like a compliant mechanism and give the robot good feedback, it becomes an advantage.

AI control turns compliance into precision

Compliant fingers can grasp fragile objects with less force, but only if you can estimate contact and control slip. This is where modern AI in robotics fits naturally:

- Tactile ML models classify contact states (no contact / stable contact / incipient slip)

- Adaptive grasp policies adjust grip force in real time

- Learning-based calibration compensates for stiffness drift over weeks of operation

A useful mental model: bio-derived fingers behave more like “soft hands” than “hard tools.” AI makes soft hands reliable.

A robot hand built from variable materials needs a controller that expects variability. That’s a better match for learning systems than for fixed-parameter control.

What sensors make bio-derived hands viable?

You don’t need a science-fair glove of sensors. A practical stack I’ve seen work in production pilots looks like this:

- Motor current + joint encoders to infer load and finger deflection

- Low-cost force sensors at the fingertip or tendon anchor

- Simple tactile arrays (even sparse ones) for slip detection

- Vision for pre-grasp planning and pose correction

Then you let AI do what it’s good at: fuse imperfect signals into a stable decision.

Safety is an underrated benefit

In collaborative environments—especially busy Q4 fulfillment and returns processing—compliance reduces injury risk. A finger that yields on unexpected contact is inherently safer than a hard jaw.

That doesn’t replace proper safety systems, but it reduces the frequency of “minor incidents” that never make it into glossy case studies and still cost real money.

Where a lobster-shell robotic hand makes sense in real automation

Answer first: Bio-derived robotic fingers are best suited for high-variation, medium-force tasks where gentle contact, fast replacement, and sustainability goals matter.

Not every application needs a humanlike hand. Most don’t. But there are pockets where hands—and especially compliant, repairable hands—beat parallel grippers.

1) Food handling and packaging

This one is almost too on-the-nose, but it’s practical. Food operations already manage organic waste streams and cleaning protocols. Compliant, high-friction fingers can improve grasping of:

- irregular produce

- baked goods in trays

- mixed-pack items that shift in cartons

If the finger material is bio-derived, you can also align sustainability metrics with process engineering.

2) E-commerce returns and kitting

Returns are chaotic: unknown items, uncertain rigidity, random packaging. A compliant hand plus vision plus learned grasping policies can reduce the number of exception picks.

The business case is usually labor risk and throughput stability, not “fancy robotics.” A hand that’s cheap to maintain matters here.

3) Lab automation and small-batch assembly

In labs, you often want gentle manipulation and fewer custom fixtures. Bio-derived fingers can be designed as application-specific fingertips—swapped weekly if needed.

A good pattern is:

- keep the actuators and palm durable and standardized

- treat fingers as consumables designed for quick replacement

4) Education and rapid prototyping (with a serious twist)

Universities and R&D teams iterate quickly. A material that can be fabricated locally and tuned for compliance is valuable.

The serious twist: those prototypes become tomorrow’s products. Materials decisions made in a lab often fossilize into production designs. Starting sustainable is easier than retrofitting later.

Design and manufacturing: how you’d actually build this

Answer first: The most credible path is a hybrid design: durable actuators and skeleton, bio-derived compliant fingers, and AI-driven calibration to keep performance stable.

A lobster-shell finger won’t replace every component. The smart approach is to separate what must be stable from what benefits from compliance.

A practical architecture

- Palm + actuation: metal or high-grade polymer, sealed, serviceable

- Transmission: tendons or cable drives for remote actuation

- Finger modules: bio-derived composite “bones” + compliant joints

- Surface layer: replaceable high-friction skin (could also be bio-based)

This modularity makes sustainability real. If a finger wears out, you don’t scrap the whole hand.

AI-enabled quality control for bio-derived parts

Bio-derived manufacturing needs measurement. The good news: AI vision and simple mechanical tests can enforce consistency.

A pragmatic QC loop:

- Scan geometry (camera + photogrammetry or structured light)

- Run a bend test to estimate stiffness within a tolerance band

- Assign a calibration profile to that finger module

- Store the profile in the robot’s asset management system

This is where AI-driven optimization shines in manufacturing: not making everything identical, but making outcomes consistent.

Durability and washdown: address it early

If you’re planning for food or pharma environments, you’ll need to test:

- moisture absorption and swelling

- chemical resistance to cleaning agents

- fatigue life under repeated bending

Bio-derived doesn’t mean “fragile,” but it does mean you can’t assume the same behavior as ABS or nylon.

People also ask: practical questions about shell-based robotics

Answer first: Most objections are valid—until you design the system around them.

“Isn’t shell material too brittle?”

It can be, if processed poorly or used like a rigid beam. In a compliant finger, you design for controlled flexure and distribute stress. Composites and layered structures can also improve toughness.

“Will it smell or attract contamination?”

Not if it’s properly processed. Chitin/chitosan-based materials used in industry are refined polymers, not raw shells. The design still needs hygienic surfaces and cleanability like any food-grade tool.

“Is it actually cheaper?”

Raw feedstock can be cheap, but processing and certification add cost. The economic win often comes from lower downtime and easier part replacement, not raw material price alone.

“What does AI add beyond standard control?”

Standard control assumes stable mechanics. Bio-derived parts drift with humidity, aging, and lot variation. AI adds adaptive calibration, slip-aware grasping, and condition monitoring so performance stays consistent without constant manual tuning.

What to do next if you’re evaluating sustainable robotic hands

Answer first: Treat this as a pilot opportunity: validate grasp performance, hygiene/durability, and maintenance economics—then decide whether bio-derived fingers beat your current end effectors.

If I were running an automation program and wanted to explore bio-derived robotic hands, I’d start with a disciplined, low-drama plan:

- Pick one task with frequent gripper exceptions (slip, damage, mispicks)

- Define success metrics: pick rate, damage rate, downtime, finger replacement time

- Instrument the hand: current, encoder, and at least basic force/tactile sensing

- Run a 4–8 week trial to capture drift, wear, and cleaning effects

- Calculate the real cost: spares, labor time, and line interruptions

The goal isn’t to prove a point about sustainability. It’s to decide if sustainable design also improves operations.

December is a good time to plan this. Many teams are already reviewing Q4 throughput issues and setting 2026 automation budgets. A small pilot now can shape a bigger deployment when capital opens up.

Bio-derived robotic fingers made from lobster shells are a reminder that materials and intelligence are converging. Sustainable robotics won’t win by being virtuous; it’ll win by being maintainable, safe, and consistent under messy real-world conditions.

If you’re considering a sustainable robotic hand for your line, the question worth asking is simple: where would adaptive, sensor-driven dexterity eliminate your most expensive “human workaround”?