Robots learn faster when they combine explicit ratings with implicit human cues. Here’s how to design feedback loops that work in real operations.

Robots That Learn From You: Explicit + Implicit Feedback

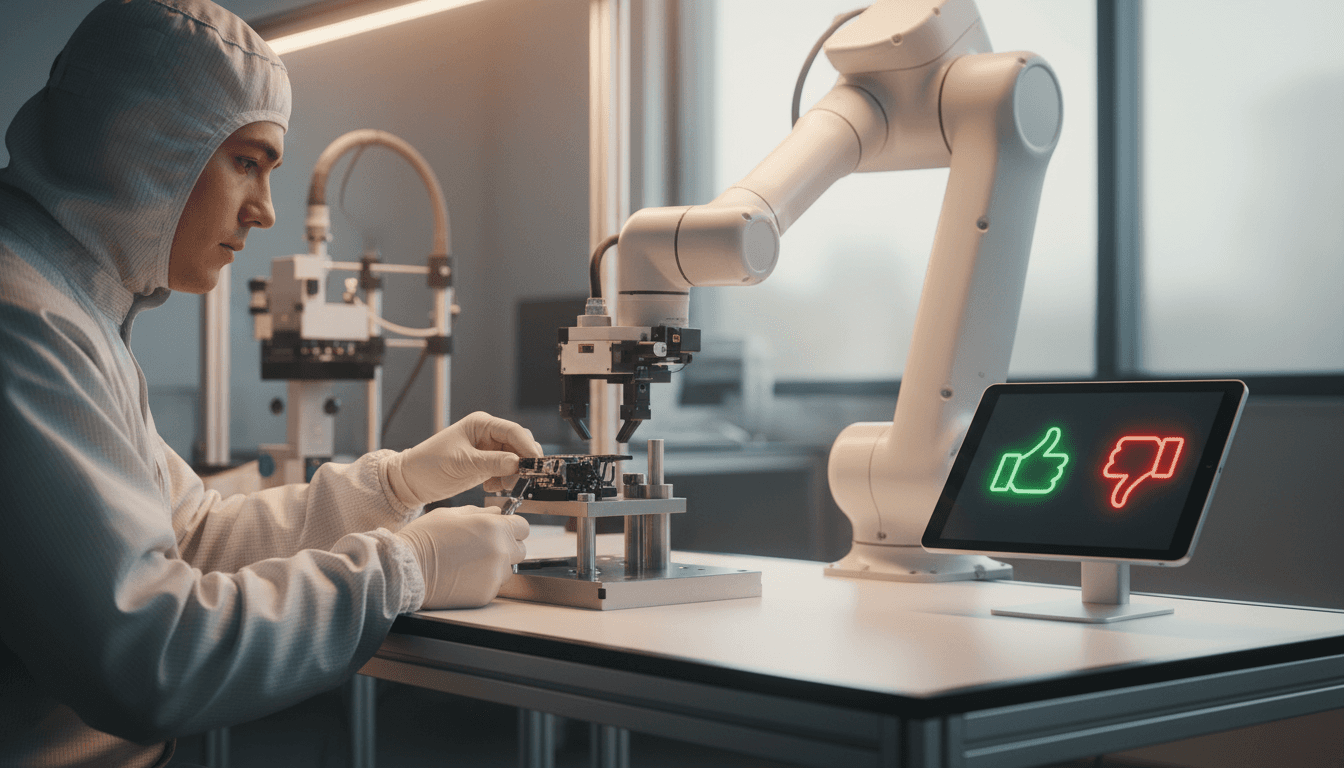

Most companies get human-in-the-loop robot training wrong because they treat people like labeling machines. Press “good” or “bad,” repeat for a few days, and the robot will somehow “get it.” In real workplaces—fulfillment centers in peak season, hospital wards, or busy production lines—people don’t have time to babysit a robot.

Kate Candon, a Yale PhD researcher in human-robot interaction, is working on a more realistic idea: robots should learn from both explicit feedback (buttons, ratings, spoken “no”) and implicit feedback (what you do next, how you correct the robot, what you choose to ignore). The practical payoff is simple: faster robot adaptation with less operator burden, especially for the messy part of automation—human preferences.

This matters because preference mismatch is where deployments quietly fail. Not with dramatic crashes, but with friction: robots that technically work yet slow teams down, annoy staff, and get sidelined.

Explicit vs. implicit feedback: the difference that changes everything

Explicit feedback is what you deliberately tell the robot. Implicit feedback is what the robot can infer from your behavior while you’re just trying to get your job done. That distinction isn’t academic—it drives cost, adoption, and performance in the field.

Explicit feedback examples:

- Tapping a “good job / bad job” button

- Giving a star rating after a task

- Saying “stop,” “that’s wrong,” or “do it like this”

Implicit feedback examples:

- Reordering items the robot staged incorrectly

- Moving an object aside because it arrived too early

- Pausing, hesitating, or changing your plan after the robot acts

- Choosing not to use the robot’s suggestion (silent rejection)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: explicit feedback is cleaner data, but it’s scarce. People get busy, they forget, and they don’t want yet another interface.

Implicit feedback is the opposite: abundant but ambiguous. A head shake might mean “no,” or it might mean “I’m thinking.” A frustrated face might be about the robot—or about something else entirely.

Candon’s core stance is the right one: don’t pick one stream and pretend it’s enough. Combine them.

Why “implicit-only” robot learning breaks in the real world

Implicit signals are only useful when the robot has the right context. Otherwise, you train the system on noise.

Candon described a moment from an earlier study where a participant looked confused and upset. If you saw only the facial expression, you’d label it negative feedback about the agent. But the context revealed the real cause: it was the participant’s first time losing a life in the game. The reaction wasn’t “bad robot,” it was “wait—what just happened to me?”

That example generalizes to factories, hospitals, and logistics:

- A picker grimaces because a tote is heavy, not because the robot chose the wrong bin.

- A nurse moves quickly because a patient alarm sounds, not because the robot is in the way.

- A line worker pauses because upstream supply is late, not because the cobot’s handoff is wrong.

If your robot treats every reaction as feedback about its last action, you don’t get learning—you get mislearning.

My take: implicit feedback is powerful, but it’s not “free.” You pay for it with modeling complexity: context tracking, task-state inference, and careful UI/UX so the robot knows when not to learn.

A practical path: combine signals so the robot learns faster

The most workable approach is a hybrid policy: use implicit behavior to propose what to learn, and explicit feedback to confirm (or correct) the interpretation.

Candon’s current framework starts with a pragmatic choice: treat human actions in the task as implicit feedback. Instead of guessing emotions first, the robot watches what you do—how you proceed, what you pick up next, what you correct. Then it maps human actions to the robot’s action space through an abstraction.

That may sound small, but it’s a big deal for deployment:

- It avoids the hardest perception problem upfront (high-variance facial cues across people and cultures).

- It ties learning to task progress, which naturally provides context.

- It creates a clean handoff to explicit feedback when needed.

The “ask at the right moment” trick

Candon’s prior work on explicit feedback found a predictable issue: people don’t give much feedback during a task because they’re focused on doing the task.

So the question becomes: when should a robot ask for explicit feedback so it’s not annoying—and actually improves learning?

Two design lessons from that research translate well to business settings:

- Timing matters more than frequency. Asking constantly drives fatigue and worse task performance.

- Language framing affects trust even when it doesn’t change behavior. A “we” framing (“so we can be a better team”) made people feel better about the feedback they gave, even if it didn’t increase the volume.

The opportunity in a combined system is straightforward: use implicit cues to detect “high-information moments,” then request explicit confirmation.

Practical high-information moments include:

- Right after the robot tries a new behavior

- Immediately after a human corrects or overrides the robot

- When the robot detects hesitation or repeated micro-corrections

This is where explicit + implicit feedback becomes more than theory—it becomes an interaction design pattern.

The pizza-making example is a stand-in for every real deployment

Cooking is a great research testbed because it has rules and preferences. There’s a recipe, but there’s also style: order of steps, personal taste, and how much help you want.

That’s the same structure you see in automation:

- Warehousing: pick rules are objective, but staging preferences vary by team and shift.

- Manufacturing: torque specs are fixed, but handoff timing and tool placement are personal.

- Healthcare: protocols are strict, but bedside workflows differ by clinician.

Candon’s preference examples are the point: one person wants the robot to do the dishes while they cook; another wants it to do all the cooking. Translate that to the shop floor: one operator wants a cobot to preload parts; another wants it to only handle heavy lifts.

Preference learning is the real bottleneck for collaborative robots. Not grasping. Not navigation. Preference alignment.

Why preference learning can’t be “data hungry” in 2026

Candon calls out a deployment reality many teams ignore: if users still have to correct the robot after days of use, they stop using it.

This is exactly what happens when preference learning requires long exploration:

- Operators create workarounds

- Supervisors disable autonomy features

- The robot becomes a glorified actuator instead of a collaborator

A combined explicit/implicit approach targets the only metric that really matters for adoption:

Time-to-acceptable behavior beats peak performance.

If you can get a robot to “good enough for this team” quickly, you earn the right to optimize later.

What this means for robotics teams in manufacturing, healthcare, and logistics

You don’t need a humanoid robot to benefit from this. The same feedback design applies to AMRs, cobots, pick-assist systems, and teleoperation copilots.

Here’s how to operationalize the idea.

1) Treat human corrections as training data (with guardrails)

If a worker re-stacks a tote, reorients a part, or changes the robot’s suggested sequence, that correction is a signal. Capture it.

But add guardrails so you don’t learn the wrong lesson:

- Log task state (what else was happening in the environment)

- Detect exogenous interruptions (alarms, shortages, rush orders)

- Weight corrections differently when the human is under time pressure

2) Add “confirmation prompts” only when the model is uncertain

The best feedback UI is the one users barely notice.

Use a simple rule: only ask for explicit feedback when the robot’s interpretation of the implicit signal is low-confidence.

Examples:

- “I noticed you moved the kit to Station 3. Should I stage kits there by default for this job?”

- “I handed you the wrench, but you set it aside. Wrong tool, or wrong timing?”

Short. Specific. Easy to answer.

3) Design for multiple people, not a single “teacher”

Candon is interested in extending dyadic interaction (one human, one robot) to group settings. That’s where most real deployments live.

In group environments, you need policies for:

- Whose preference wins (lead operator, role-based rules, shift policies)

- How the robot handles conflicting signals

- How quickly preferences decay or transfer across shifts

If you ignore multi-user reality, your system will look “smart” in pilots and frustrating in production.

4) Be careful with faces, gestures, and “emotion AI” claims

Candon’s roadmap includes adding visual cues like facial reactions and gestures. That’s exciting—and risky.

My stance: use visual cues as secondary signals, not primary truth. They’re high variance and context-dependent. In many workplaces, they’re also sensitive from a privacy and compliance standpoint.

A safer approach is:

- Start with task actions (highest signal-to-noise)

- Add lightweight non-identifying cues (body orientation, distance, timing)

- Only then consider facial cues, with explicit consent and clear value

Where language fits: explicit, implicit, or both?

Language is messy in the best way. “Good job” can be praise, sarcasm, or a polite dismissal. Tone matters.

A practical split that works in real systems:

- Explicit language: short commands and confirmations (“Stop,” “Yes,” “Do that again”)

- Implicit language: commentary and tone that correlates with satisfaction (“Sure…”, “Finally,” laughter)

If you’re building with large language models in the loop, don’t overreach. Use them to:

- Generate clarification questions

- Summarize what the system thinks the user prefers (“You want tool A before tool B, correct?”)

- Convert feedback into structured updates (preferences, constraints, rankings)

But keep safety-critical actions governed by deterministic policies and verified constraints.

A field-ready checklist for explicit + implicit feedback systems

If you want robots that learn from human feedback without burning out your operators, build the system around these rules:

- Default to implicit signals (actions, corrections, acceptance/rejection) because they’re abundant.

- Use explicit feedback as a validator, not the main data source.

- Ask for feedback at high-information moments, not on a timer.

- Model context aggressively so you don’t learn from the wrong cause.

- Plan for multiple users and conflicting preferences from day one.

- Measure time-to-adoption, not just final policy reward.

That checklist won’t make learning easy—but it makes it realistic.

Where this is going in 2026: robots that adapt without extra work

Robots learning from explicit and implicit feedback isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between automation that scales and automation that stalls.

As teams head into another year of labor constraints, tighter margins, and higher expectations for throughput, the bar is moving: robots have to adapt to humans, not the other way around.

If you’re evaluating robotics for manufacturing, healthcare, or logistics, push vendors and internal teams on one question: How does the system learn my team’s preferences in the first week—without turning us into full-time trainers?

The answer will tell you whether you’re buying a robot—or buying a long-term behavior management project.