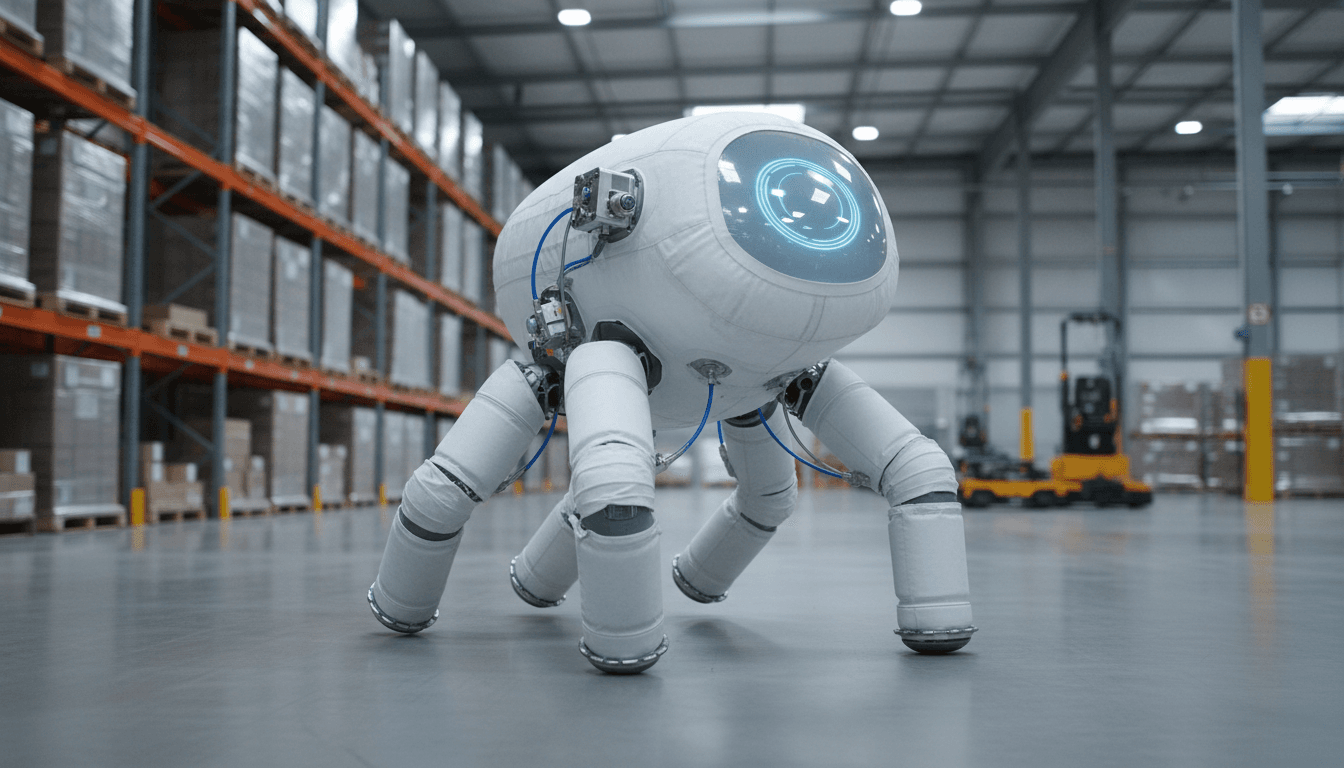

Air-powered soft robots can walk using physics instead of complex control. See where this fits in AI robotics for logistics and healthcare.

Air-Powered Soft Robots That Walk Without Complex Control

A lot of robotics budgets get burned on the least glamorous part of the system: control. Not the sensors. Not the grippers. The endless tuning, edge cases, and “why did it fall over this time?” debugging that comes with getting legs to move reliably.

That’s why the recent idea behind an air-powered soft robot with tube-like legs that “walks” using physics instead of circuits is more than a cute lab demo. It’s a reminder that locomotion doesn’t always need heavy onboard electronics—or a neural network micromanaging every step. Sometimes, you can get repeatable motion by designing the body so that the environment and the materials do the controlling.

For teams working on AI in robotics & automation, this matters in a very practical way: when the mechanism handles more of the behavior, AI can shift from real-time step control to higher-value decisions like routing, safety, exception handling, and task planning. That’s where automation projects start to scale.

Physics-based locomotion: the “controller” is the body

Physics-based locomotion replaces complex gait control with mechanical rules baked into the robot’s structure. In soft robotics, that often means using inflation/deflation cycles, elastic materials, and geometric constraints so motion emerges automatically.

The RSS summary describes a soft-bodied robot that runs on inflatable tube-legs and uses a physical phenomenon to “automatically move” those legs—minimizing conventional control electronics. Even without the full paper, the concept fits a known pattern in soft robotics: if you create asymmetry (in friction, stiffness, or airflow resistance), the same pressure input can produce a directional, repeating gait.

What’s likely happening under the hood (without overhyping it)

To get walking from air, designers typically combine a few ingredients:

- Inflatable chambers that expand in a predictable direction

- Passive valves or fluidic elements that alternate airflow between legs (a pneumatic “oscillator”)

- Anisotropic friction (e.g., foot shapes or materials that grip in one direction and slip in another)

- Elastic return forces that reset the leg when pressure drops

The key point isn’t the exact mechanism—it’s the design philosophy:

If you can encode the gait into the robot’s morphology, you don’t have to compute it step-by-step.

That’s a big deal for field robotics and cost-sensitive automation where reliability and maintainability beat fancy demos.

Why “less AI” can make AI robotics more scalable

Most companies get this wrong: they assume smarter robots require more onboard intelligence. In practice, the fastest path to scalable automation is often the opposite: reduce the number of things that need intelligence in the first place.

A physics-driven walker changes the engineering stack:

Fewer failure points, simpler commissioning

Traditional legged locomotion stacks can include IMUs, joint encoders, torque control loops, gait planners, slip estimators, and fallback behaviors. That’s a lot to validate. A pneumatic, body-driven gait can remove or simplify:

- High-frequency joint control

- Multi-sensor fusion for balance

- Complex state machines for gait transitions

Commissioning becomes closer to “set pressure, confirm motion, verify safety limits.” That’s a very different operational model—especially appealing in warehouses, hospitals, or labs where technicians need predictable behavior.

Lower compute and power requirements

If the robot doesn’t need to run a heavy control loop, you can often:

- Use cheaper processors

- Reduce battery size (or shift power to pneumatics)

- Reduce heat and enclosure complexity

That can be the difference between a pilot and a product.

AI shifts to where it actually pays off

When the gait is passive or semi-passive, AI can focus on:

- Navigation: “Where should I go?”

- Coordination: “When should I move, stop, yield, or reroute?”

- Perception: “Is that a person, a cart, a spill, a dropped syringe?”

- Anomaly handling: “Something changed—what’s the safe fallback?”

In other words: physics handles cadence; AI handles judgment.

Where air-powered soft robots fit in real automation

Air-powered soft robots make sense when you value compliance, low cost, and safe interaction over speed and payload. That’s not a niche anymore—especially heading into 2026, as organizations look for automation that’s deployable without major facility redesign.

Logistics and warehouse micro-mobility

Hard-wheeled AMRs dominate warehouse transport, but there are gaps:

- Narrow aisles, temporary layouts, and mixed flooring

- Areas where compliance reduces damage risk (pack stations, returns, kitting)

- “Last-meter” movement around humans and clutter

A soft, air-driven walker won’t replace an AMR hauling 500 kg. But it could fill roles like:

- Moving light totes in dense work cells

- Navigating fragile goods zones

- Operating in pop-up seasonal areas (a real December problem)

Healthcare and assisted living

Healthcare robotics often fails not because perception is impossible, but because the systems feel too rigid for human environments. Soft robots change that tradeoff.

Air-powered, compliant locomotion can support:

- Mobile supply delivery in busy corridors

- Bedside support devices that must be safe on contact

- Robots that operate quietly and gently around patients

And since hospitals care about uptime and serviceability, simpler control architectures are a genuine advantage.

Inspection in constrained or delicate spaces

Soft locomotion is a strong fit for:

- Industrial facilities with tight access paths

- Labs where bumping equipment is unacceptable

- Temporary construction environments

If the robot can keep moving with minimal sensing, it becomes a “go-anywhere” platform for small sensors (thermal, gas, camera) without the integration overhead.

The engineering tradeoffs (and how to design around them)

Physics-based locomotion isn’t magic. It’s a different set of constraints. If you’re evaluating this approach for automation, these are the questions that matter.

Tradeoff 1: Precision vs. robustness

A passive pneumatic gait tends to be robust but less precise than actively controlled legs.

Design workaround: treat motion as a primitive, not a continuous variable. Instead of “exactly 0.73 m forward,” the primitive is “advance one gait cycle,” and higher-level planning handles the rest.

Tradeoff 2: Pneumatics supply and deployment complexity

Air isn’t free. You need:

- Onboard pumps/compressors or

- A tethered supply or

- Swappable compressed air cartridges

Design workaround: match the deployment to the environment.

- Factories and labs already have compressed air infrastructure.

- Mobile deployments may prefer compact pumps plus small reservoirs.

Tradeoff 3: Repeatability across surfaces

Friction differences can change gait speed, direction, and stability.

Design workaround: use minimal sensing (not zero sensing). A single IMU or pressure sensors can detect drift or stall and trigger simple corrections.

Tradeoff 4: Maintenance and lifecycle

Soft materials fatigue. Seals leak. Valves clog.

Design workaround: design for modularity—legs as consumables, quick-connect tubing, and self-check routines that measure pressure decay.

If you’re building for operations teams, this matters more than a perfect demo.

The sweet spot: “physics first” hardware + “AI last-mile” control

The best architecture here is hybrid: let physics generate the gait, then let AI handle the messy parts of real environments.

Here’s a practical way to think about it:

A reference stack that scales

- Morphological control (mechanical): body geometry, compliance, friction design

- Pneumatic rhythm (simple): passive fluidic oscillators or basic timed valves

- Supervisory control (lightweight): start/stop, direction switching, safety interlocks

- AI layer (high value): perception, mapping, task planning, exception handling

This architecture reduces the need for high-frequency learning-based control—while still getting the benefits of AI where it actually improves outcomes.

What AI adds that physics can’t

- Adaptation: detect when the floor changed (wet tile vs. carpet) and adjust pressure or cycle timing

- Safety: predict human motion and choose conservative behaviors automatically

- Operations: predict component wear from pressure/flow patterns and schedule maintenance

A line I use with teams: Use AI to manage uncertainty, not to generate every movement.

FAQ-style answers your team will ask anyway

Can robots move without AI?

Yes. Many robots have always moved without AI. What’s different here is using physics-based locomotion to reduce even traditional control complexity, not just AI.

Is this approach only for “toy” robots?

No. It’s best for light payloads, safe human interaction, and low-cost deployment. Those are serious requirements in healthcare, inspection, and dense logistics cells.

Will physics-based walking replace conventional legged robots?

No, and it shouldn’t. Conventional legged robots win on speed, payload, and precise foot placement. Physics-driven soft robots win on simplicity, compliance, and cost.

Where does AI fit if the robot already walks on its own?

AI becomes the operator brain: navigation, perception, coordination, safety, and maintenance prediction. That’s where leads and ROI usually come from.

What to do next if you’re exploring automation with soft robotics

If this idea hits a nerve—because you’re tired of overcomplicated control stacks—here are concrete next steps that work in real projects:

- Pick a task where compliance is a feature, not a compromise. Healthcare delivery, inspection, or light logistics are good starting points.

- Define success metrics that match the mechanism. Think “cycles completed without intervention,” “safe contacts,” and “mean time to recovery,” not just top speed.

- Prototype the pneumatic architecture early. Air supply, valves, and tubing routing will define your maintainability.

- Add minimal sensing for supervision. Pressure sensors + IMU goes a long way.

- Use AI for exceptions and planning. That’s how you keep complexity from creeping back in.

Air-powered soft robots that walk using physics instead of complex control aren’t a rejection of AI. They’re a reminder that better automation often comes from simplifying the problem before you throw intelligence at it.

If you’re building robotics for logistics, healthcare, or inspection, the real question is: Which parts of your system are you controlling because you have to—and which parts could you redesign so they control themselves?