AI robodogs are moving from demos to deployments. Learn how speed and agility translate into real ROI across logistics, manufacturing, healthcare, and rescue.

AI Robodogs: Speed, Agility, and Real-World Work

A few years ago, most quadruped robots looked impressive in demos but struggled with the unglamorous stuff: carrying weight, staying stable on messy floors, and surviving the daily abuse of real operations. That’s why the newest wave of heavy-duty robodogs—like Unitree’s latest quadruped highlighted in Paul Ridden’s watch-and-react coverage—matters. The headline isn’t “it can walk.” The headline is it can move fast, stay agile, and take a hit.

For manufacturing leaders, warehouse ops teams, and anyone responsible for field safety, speed and agility aren’t party tricks. They’re the difference between a robot that’s fun to watch and a robot that earns a badge, a budget line, and a permanent job.

This post breaks down what “speed and agility” actually mean in industrial terms, where AI-enabled quadruped robots fit (and where they don’t), and how to evaluate robodogs for logistics, inspection, healthcare support, and rescue.

Why speed and agility are now KPIs for automation

Speed and agility have become key performance indicators because dynamic environments punish rigid automation. If your facility is perfectly structured, a fixed conveyor and an arm behind a cage can run for years. But the minute you move into semi-structured spaces—aisles with temporary pallets, outdoor yards, construction-adjacent zones, hospitals, disaster sites—mobility becomes the bottleneck.

Quadrupeds compete in that messy middle:

- Faster response than wheeled bots when routes aren’t predictable

- Better terrain handling where curbs, hoses, ramps, grates, and debris exist

- Higher survivability when bumps and falls aren’t hypothetical

And “agility” isn’t a single feature. Operationally, it’s a bundle:

- Gait adaptation: switching foot placement and rhythm when the surface changes

- Disturbance recovery: staying upright after a shove, slip, or sudden payload shift

- Turning and lateral motion: navigating tight corners and crowded work zones

- Task continuity: resuming a mission after a near-failure without a human reset

Here’s the thing about agility: you can’t bolt it on later. If the robot’s control stack can’t interpret the world quickly and adjust its body plan, you end up slowing the robot down to keep it safe. That kills ROI.

What makes a “heavy-duty” robodog practical (not just impressive)

A tough, durable quadruped is valuable because it reduces the hidden costs—downtime, repairs, and babysitting labor—that sink pilot projects. Many teams buy the robot and underestimate everything around it: operator training, charging logistics, spares, software updates, network coverage, and safety sign-off.

Unitree’s positioning (tough, durable, fast, agile) signals a push toward robots that can handle routine knocks and still keep moving. For real deployments, “heavy-duty” usually means four things.

1) Payload and stability under load

A quadruped that can carry tools, sensors, or medical supplies isn’t automatically useful. The hard part is staying stable while doing it.

Practical tests I like:

- Can it accelerate and stop without pitching the payload?

- Does it maintain stability while turning tightly?

- Can it step over obstacles without swinging the load into people or shelving?

If your use case includes doors, elevators, or stairs, stability becomes the defining constraint—not top speed.

2) Durability you can budget around

Durability shows up as:

- Ingress protection (dust, splashes)

- Thermal tolerance (cold docks, hot plant rooms)

- Shock resistance (minor falls, collisions)

- Serviceability (how fast you can swap a leg module, battery, or sensor)

In December operations—icy yards, wet entryways, condensation from temperature swings—durability isn’t a “nice to have.” It’s the requirement.

3) Mobility that actually reduces human work

A robodog should either:

- Replace a repetitive walking route (inspection, rounds, readings)

- Extend coverage (night shifts, large yards)

- Reduce exposure (hazards, smoke, unstable structures)

If it only adds a new workflow—“someone must escort it, reset it, and clear its path”—you’re building a robot parade, not automation.

4) The AI stack that makes it adaptable

AI is what turns mobility hardware into a useful field worker. Not “AI” as a marketing label, but specific capabilities:

- Perception: detecting obstacles, drop-offs, people, and changing terrain

- Localization and mapping (SLAM): knowing where it is when GPS isn’t available

- Motion planning: choosing stable footholds and safe routes in real time

- Policy learning / control optimization: improving gait efficiency and recovery

The simplest test: if you slightly change the environment (new pallet stack, a blocked aisle, a puddle), does the robot adapt or fail?

Where AI-powered quadruped robots fit best in 2026 operations

Quadruped robots earn their keep when the environment changes faster than you can re-engineer it. Here are the most practical, near-term fits I’m seeing across industry and public services.

Manufacturing: inspections, readings, and “boring” compliance

Manufacturing plants are full of tasks that are simple but constant:

- Checking gauges and indicator lights

- Thermographic scans for overheating components

- Acoustic monitoring for failing bearings

- Leak detection (gas, steam, compressed air)

A robodog becomes compelling when it can do multi-sensor rounds and write results straight into your CMMS/EAM workflow. The speed/agility angle matters because plants aren’t tidy: temporary barriers appear, hoses snake across walkways, and maintenance zones shift daily.

A strong deployment pattern:

- Fixed patrol routes + exception handling

- “Stop and scan” behaviors at known assets

- Automated issue escalation (photo + location + severity)

If you can cut even 60–90 minutes of manual rounds per shift across multiple buildings, the economics start to look real.

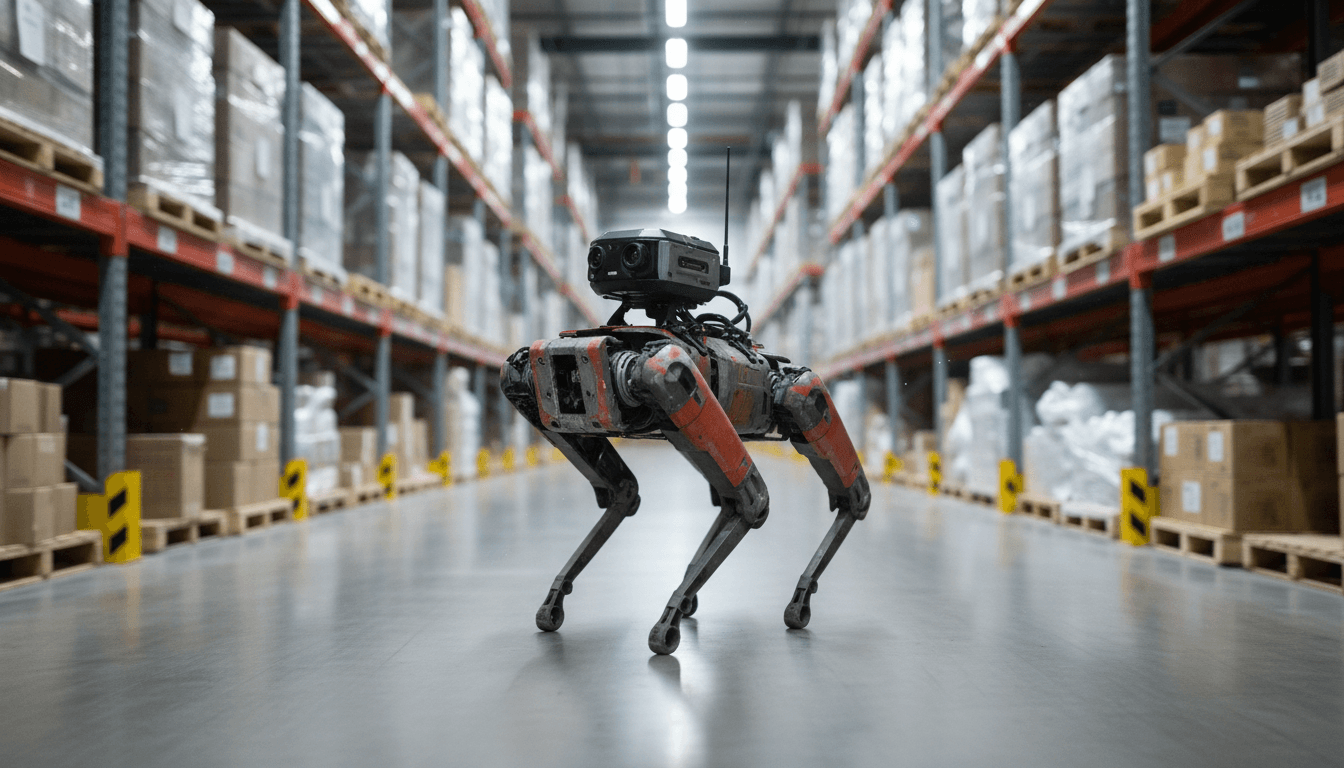

Logistics: yard patrols, trailer checks, and inventory visibility

Warehouses are predictable in theory and chaotic in practice—especially during peak and post-peak periods. A fast, agile quadruped can help with:

- Yard and perimeter patrols (after-hours)

- Spot checks on dock doors and trailer seals

- Locating mis-staged pallets using vision tags/markers

- Monitoring blocked fire aisles and safety hazards

Wheeled robots can do some of this, but quadrupeds win when:

- The surface is uneven (yards, ramps, threshold plates)

- Routes include obstacles that would stop a wheeled bot

- You need reliable motion in crowded, shifting layouts

Speed matters because patrol utility scales with coverage. A slow robot that takes two hours to do a loop doesn’t reduce labor; it just creates a second job.

Healthcare: delivery support and overnight observation rounds

Hospitals are the definition of dynamic environments: people, carts, sudden obstructions, changing room states. Quadrupeds can support:

- Night delivery of small items (linen, meds in controlled workflows)

- Facility checks (doors, spills, blocked corridors)

- Remote “eyes-on” support for security teams

I’m not convinced quadrupeds are the first choice for patient-facing tasks. But for back-of-house mobility—especially in older buildings with awkward layouts—the agility advantage can outweigh the novelty risk.

Security and rescue: when mobility is the product

In rescue, mobility is the mission. A quadruped that can carry sensors into unstable areas can reduce risk to humans.

High-value scenarios:

- Post-fire structure checks (thermal + gas sensors)

- Industrial incidents (chemical plants, refineries)

- Search support in low visibility (mapping + audio)

A durable robodog matters because rescue environments don’t offer second chances. Fast recovery from slips and pushes isn’t a demo stunt—it’s survival.

A practical rule: if a human would hesitate to enter, a robot should be able to go first.

Buying checklist: how to evaluate a robodog for real work

The best quadruped robot for your business is the one that integrates with your operations, not the one with the flashiest video. Here’s the evaluation approach I’d use if I were responsible for a pilot.

Define the job in metrics (before you pick the robot)

Write down the numbers:

- Distance per run (meters)

- Number of stops (assets checked)

- Time window (minutes)

- Payload needed (kg)

- Minimum runtime (minutes)

- Data output (photos, thermal, gas, readings)

If you can’t quantify the job, the pilot will drift into “cool robot” territory.

Run a “messy floor” test

Your facility has edge cases. Bring them into the test:

- Wet patches and reflective floors

- Thresholds and small ramps

- Tight turns around endcaps

- People walking through the path

If the robot only performs on the cleanest route, you’re not testing deployment readiness.

Inspect the autonomy boundaries

Ask directly:

- What requires teleoperation?

- How does it handle map changes?

- What happens after a fall?

- Can it safely stop around humans, and how is that verified?

Autonomy isn’t binary. Most teams succeed by designing a workflow where the robot is autonomous most of the time, and humans step in for rare exceptions.

Plan for integration and governance

Where pilots fail:

- No clear owner for robot uptime

- No process for updating maps and routes

- No integration into tickets/work orders

- Unclear safety rules around people and vehicles

Minimum viable governance:

- A named operator and a named maintainer

- A change-control process for routes and software

- A clear incident playbook (stop, retrieve, review)

The bigger trend: quadrupeds are becoming “platforms,” not projects

The most meaningful shift is that robodogs are turning into sensor-and-software platforms you can redeploy. One month it’s inspection rounds. Next month it’s yard patrols. After that it’s emergency response drills.

That flexibility comes from the AI stack and the ecosystem around it:

- Swappable sensors (RGB, thermal, gas, LiDAR)

- Mission planning tools

- Fleet management dashboards

- Standard integration points into existing systems

If you’re trying to justify a quadruped purchase, don’t pitch a single use case. Pitch a sequence of use cases where each one reuses the same core investment.

What to do next if you’re considering an AI robodog deployment

Start with one route and one measurable outcome. I’ve found that the teams that win don’t start with “full autonomy everywhere.” They start with a patrol that’s annoying for humans, safe for the robot, and easy to measure.

A strong first deployment is often:

- A repeatable inspection loop (same assets, same checks)

- A night patrol with clear exception thresholds

- A sensor mission that’s valuable even if it runs slower than a human

Then scale.

If you’re evaluating a heavy-duty, AI-powered quadruped robot for logistics, manufacturing, healthcare support, or rescue, the smartest question isn’t “How fast can it run?” It’s this: How many real tasks can it complete this week, with your real constraints, without a human babysitter?