Dark patterns in loan apps can turn quick credit into a debt trap. See what Ghana can learn from Nigeria—and how AI can enforce ethical lending design.

Dark Patterns in Loan Apps: Ghana’s AI Warning Signs

Nigeria’s digital loan apps didn’t become controversial because lending is “bad.” They became controversial because product design made taking expensive credit feel like tapping “OK.” One-click borrowing, confusing fees, and pressure-filled reminders can turn a short-term cash need into a long-term problem—especially for workers and traders whose income comes in bursts.

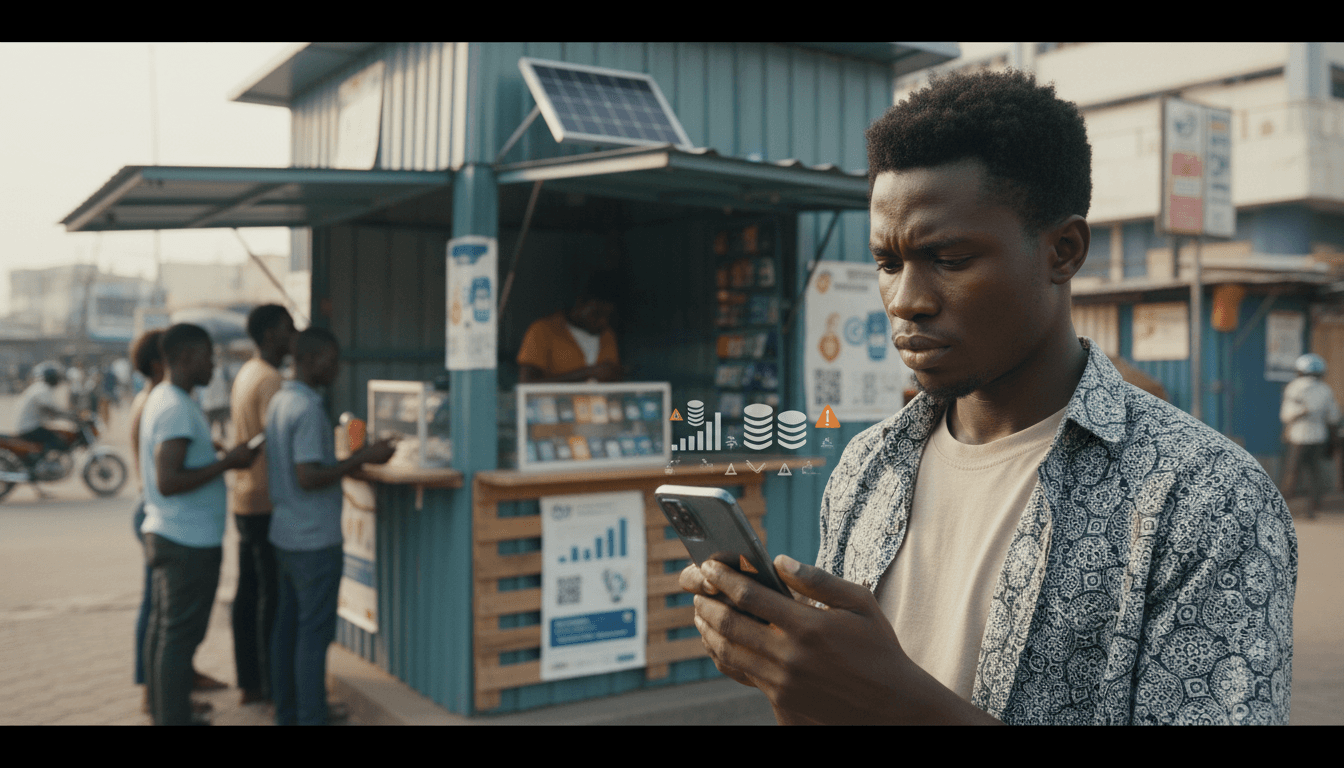

That Nigerian experience matters directly to Ghana’s fintech and mobile money future. Ghana is building a stronger digital finance ecosystem—mobile money is mainstream, and more digital credit options are showing up inside wallets and apps. The risk is simple: if we copy the growth tactics without copying the consumer protections, we’ll import the same debt-trap dynamics.

This post sits inside our “AI ne Fintech: Sɛnea Akɔntabuo ne Mobile Money Rehyɛ Ghana den” series for a reason. AI can automate and speed up lending decisions—but it can also be used to detect predatory patterns, enforce transparency, and keep mobile money users from being tricked by UI choices. Ethical design isn’t a “nice-to-have.” It’s the difference between financial inclusion and digital exploitation.

What “one-click debt traps” really look like in digital lending

A one-click debt trap is when a borrowing journey is designed so that the fastest path is also the most expensive path, and the user only understands the real cost after they’re already committed.

The Nigerian reporting (from the RSS summary) flags a core problem: loan apps thriving in a credit-starved market can deepen exploitation using “dark patterns.” Dark patterns are design tricks that push people into decisions they wouldn’t make if the app was straightforward.

Common dark patterns seen in loan apps

You don’t need a law degree to spot them. If you’ve used mobile apps a lot, you’ve probably felt them.

- One-tap “Accept” with buried terms: The acceptance button is huge; the repayment details are tiny.

- Pre-selected high-cost options: The app defaults to a short tenor or high fee plan that maximizes charges.

- Urgency cues that create panic: Countdown timers, “limited offer,” or repeated prompts right after denial.

- Fee stacking that’s hard to compute: Processing fees + “service” fees + penalties that aren’t shown as a single effective cost.

- Consent that’s not really consent: “Allow contacts” or “allow gallery” framed as mandatory to continue.

A simple rule: if the app makes it easier to borrow than to understand the cost, it’s not an accident.

Why these patterns hit vulnerable borrowers hardest

Answer first: dark patterns work best when people are stressed. If you’re trying to pay rent, restock a shop, or handle school fees, your brain prioritizes speed. Design that exploits stress isn’t clever—it's predatory.

In West African markets where many people are underbanked or “thin-file” (limited formal credit history), digital lenders hold all the power: they set the pricing, the tenor, the penalties, and the communication style. If the interface nudges users toward costly outcomes, borrowers lose—even if they never missed a payment before.

Ghana can learn from Nigeria without waiting for a crisis

The fastest way to “learn” is to treat Nigeria’s experience as a preview. Ghana’s fintech market is different, but the incentives are the same: acquisition targets, repayment rates, and growth metrics can tempt teams to optimize for clicks rather than consumer wellbeing.

The overlap with mobile money in Ghana

Answer first: digital lending and mobile money are converging. Many people won’t download a separate loan app; they’ll borrow inside a familiar wallet or via USSD-like flows.

That convenience is useful. But it also means:

- The trust of mobile money can rub off on a lending product that doesn’t deserve it.

- Loan offers can be pushed at the exact moment a user receives funds (salary, remittance, payments).

- Repayments can be auto-deducted, creating disputes when terms weren’t clearly understood.

If Ghana wants mobile money to keep “rehyɛ Ghana den” (strengthen Ghana), the ecosystem has to make borrowing clear, fair, and auditable.

A myth worth killing: “Users should just read the terms”

People don’t read long terms on small screens. Even if they try, many terms are written in legal English that doesn’t match how people actually budget.

The standard should be: if a reasonable person can’t predict the total cost and the worst-case outcome in 60 seconds, the product is not transparent.

Where AI helps: detect predatory design before it harms users

AI in fintech isn’t only about credit scoring. Used properly, AI becomes a consumer protection tool—one that scales.

Answer first: AI can flag risky UX patterns, pricing structures, and communication behaviors that correlate with harm. That’s exactly what Ghana needs as more digital credit products reach mass adoption.

1) AI “UX audits” that spot dark patterns

Teams already use analytics to track funnels. The ethical upgrade is to use AI to detect manipulative funnels.

What it can measure:

- Time-to-accept vs time-to-understand: If 80% of users accept in under 10 seconds, they likely didn’t read cost details.

- Scroll-depth on pricing screens: If almost nobody reaches the “fees” section, the interface is hiding it.

- A/B tests that increase borrowing but also increase distress: If a variant boosts acceptance but spikes late payments or rollovers, it’s a red flag.

A practical governance rule I like: any growth experiment that changes pricing visibility should be reviewed like a risk model change. Not “marketing.” Risk.

2) AI that predicts “harm,” not just default

Default prediction is useful for lenders. Harm prediction is useful for society.

Examples of harm signals AI can detect (using anonymized behavioral data):

- Frequent borrowing within short cycles (rollover-like behavior)

- Borrowing immediately after repayment (dependency)

- Repeated loan extensions and penalty accumulation

- Spending patterns that suggest repayment is crowding out essentials

This is where ethical lending becomes measurable: a portfolio can be profitable while still harming a segment of users. AI can identify that segment and enforce safer limits.

3) AI-powered clarity: show real cost in plain language

One of the biggest fixes is also the simplest: make the cost understandable. AI can generate personalized, plain-language summaries in English and local languages.

Good “clear cost” design looks like:

- Total repayment in Ghana cedis (not just a percentage)

- Due dates and what happens if you’re late in one sentence

- A short “worst-case” box: penalties, auto-deduction rules, and dispute steps

If an app can generate a loan offer in seconds, it can also generate a human-readable explanation in seconds.

4) AI to police collections behavior

Predatory lending often gets uglier during collections: aggressive messages, shame tactics, and excessive contact.

AI can help by:

- Classifying messages for abusive tone

- Detecting harassment frequency (too many calls/texts)

- Enforcing time-of-day limits

- Flagging attempts to contact third parties without valid consent

Put bluntly: collections can’t be a free-for-all just because repayment is hard.

What ethical digital lending should look like in Ghana (practical checklist)

Answer first: ethical design is visible in the user journey—before, during, and after borrowing. Here’s a checklist product teams, compliance teams, and even consumers can use.

Before borrowing: offer transparency you can’t miss

- Show total repayment first, then break down fees.

- Display an effective cost metric that’s consistent across products.

- Require a confirmation step that repeats: amount borrowed, total repayment, due date.

During repayment: reduce surprises

- Send reminders that include exact amount due and date/time.

- Provide grace policies that are clear (if none, say so).

- Offer partial repayment options where possible.

When things go wrong: treat distress like a risk event

- Offer restructuring options early, not after penalties explode.

- Provide one-tap access to: statement, fees charged, dispute channel.

- Prohibit any design that relies on shame, threats, or exposure.

A strong fintech brand isn’t the one that approves the fastest. It’s the one that stays trusted when money is tight.

“People also ask” (quick answers for mobile money users)

How do I know a loan app is using dark patterns?

If the app makes borrowing feel effortless but makes fees, penalties, or consent settings hard to understand, that’s a warning sign. Fast borrowing isn’t the problem—fast confusion is.

Can AI make digital lending safer for Ghana?

Yes—if it’s aimed at transparency and consumer protection, not just profit. AI can audit UX flows, flag harmful borrower cycles, and monitor collections behavior at scale.

Should Ghana regulate app design, not just interest rates?

Yes. Rates matter, but design determines decisions. Regulators and industry groups should treat manipulative UX the same way they treat misleading advertising.

A better path for AI ne Fintech in Ghana

Ghana doesn’t need to fear digital lending. It needs to fear digital lending that hides the ball. Nigeria’s loan-app controversy is a clear signal: when product design rewards speed over clarity, vulnerable borrowers pay the price.

For teams building inside mobile money and fintech, the standard should be: AI that approves credit must also protect the customer. That means AI-driven UX audits, harm monitoring, clear-cost summaries, and strict controls on collections behavior.

If you’re building, investing, or partnering in Ghana’s fintech ecosystem, ask one forward-looking question: Will your next growth experiment make borrowing clearer—or merely faster?