A 90% equity portfolio near retirement can backfire. Learn how to add safety, use GICs/bonds wisely, and protect withdrawals in volatile markets.

90% Equities Near Retirement? A Safer Portfolio Plan

A portfolio that’s 90% equities can feel totally reasonable when you’re 35 and adding money every payday. Near retirement, it becomes a different animal—because the risk that matters most changes. It’s no longer “Will the market go down?” (it will). It’s “Will a bad sequence of returns force us to sell stocks at the worst time?”

And in late 2025, that question feels extra sharp. Interest rates have been volatile for a few years, cash and GIC rates have been competitive, and markets have reminded everyone that double-digit drops can happen quickly. If you’re approaching retirement with most of your TFSA, RRSP, and non-registered accounts in stocks, you’re not “wrong”—but you’re probably underestimating the cost of bad timing.

Here’s a better way to think about it: you don’t need to become conservative across the board. You need some safety, placed deliberately, so your retirement spending can keep flowing even when markets don’t cooperate.

The real risk isn’t “stocks are risky”—it’s selling them at the wrong time

A 90% equity allocation can work for long retirements, but it can also backfire if you’re withdrawing during a downturn. This is sequence-of-returns risk: early losses plus withdrawals can permanently shrink your portfolio, even if markets recover later.

A simple illustration:

- Couple retires with $1,000,000 invested and plans to withdraw $50,000/year.

- If the market drops 20% in year one and they still withdraw $50,000, their portfolio takes a double hit.

- After a year like that, they’re not just “down 20%.” They’re down 20% and they’ve sold more shares at lower prices to fund life.

This matters more than average returns. A 90% equity portfolio might have a higher expected long-term return, but retirement success is about staying solvent through bad stretches, not winning a performance contest.

Snippet-worthy truth: A high-equity portfolio is only “aggressive” if you’re forced to sell it during a downturn.

How conservative should you be before retirement? Use a “spending floor”

The right allocation depends on when you’ll need the money—not just your risk tolerance. I’ve found the cleanest approach is building a spending floor: a bucket of safe assets that covers your near-term withdrawals so you don’t have to sell equities when markets are down.

A practical target: 2–5 years of spending in safer assets

For many Canadian households, a solid starting point is:

- 2–3 years of core spending in very safe, liquid options (high-interest savings, cashable GIC ladders, money market funds)

- another 2–3 years in high-quality fixed income (short/intermediate bonds, bond ETFs, or a GIC ladder)

If you expect to spend $70,000/year in retirement (after CPP/OAS), that could mean $140,000–$350,000 in safety-first assets.

This isn’t about market timing. It’s about time matching. Stocks are for 10+ year money. Retirement withdrawals are often “next month” money.

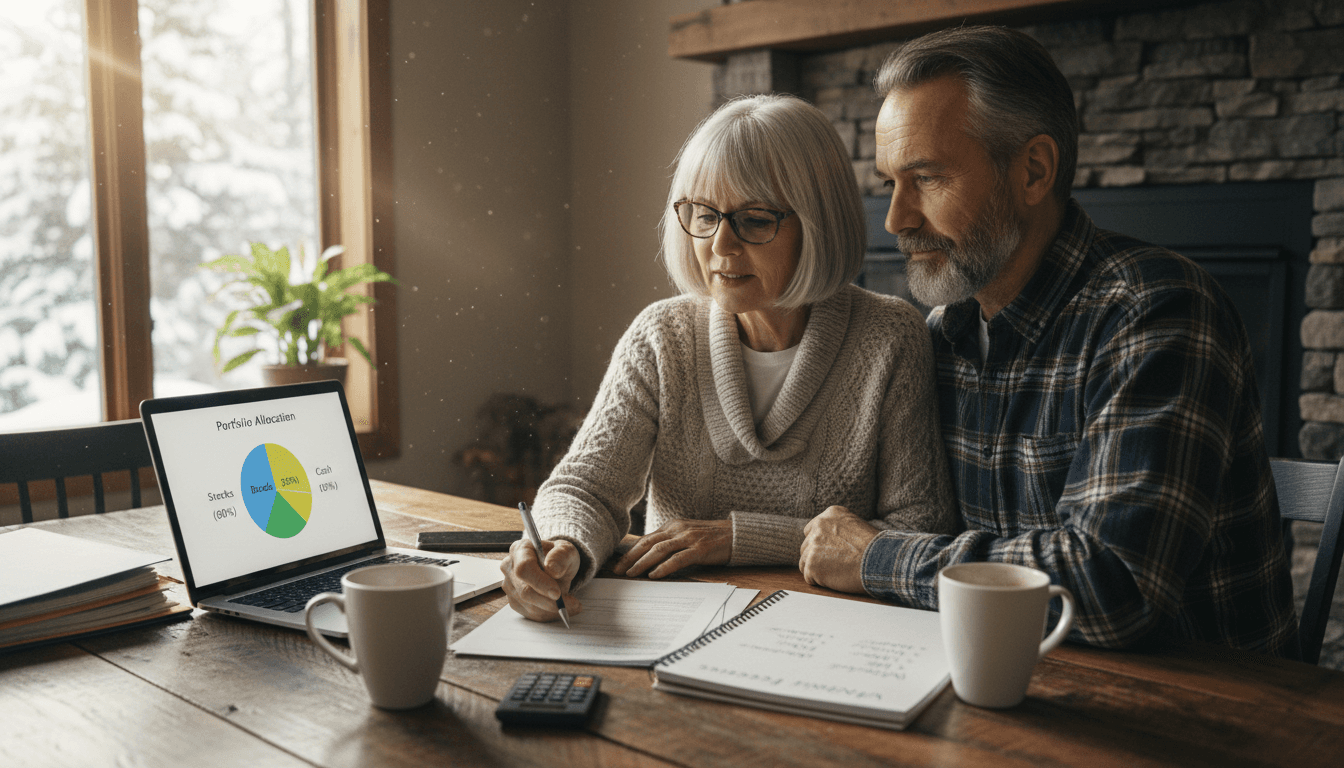

Common allocations that are reasonable near retirement

There’s no magic number, but here are ranges that are commonly workable:

- 60/40 (equities/fixed income): traditional “balanced” retirement mix, smoother ride, less upside

- 70/30: still growth-oriented, but with meaningful ballast

- 80/20: aggressive, but more defensible than 90/10 if you’ve built a cash/GIC runway

A 90% equity portfolio near retirement can make sense only if:

- you have substantial guaranteed income (pensions) covering most expenses, or

- you have a large cash/fixed income buffer, or

- you’re comfortable cutting spending sharply during bear markets

Most people don’t want that third option.

Interest rates change the math (and your opportunity set)

In the “rates near zero” era, retirees were almost forced into more risk to generate income. Higher yields change that.

Why today’s rates support a more balanced portfolio

When safe yields are non-trivial, you can fund part of your retirement plan with less volatility. Practically, that means:

- GIC ladders can cover planned withdrawals with known maturity dates.

- High-quality bonds can contribute income and diversification.

- Holding “dry powder” doesn’t feel like you’re earning nothing.

This also connects directly to the broader Interest Rates, Banking & Personal Finance theme: rate shifts affect not just mortgages, but also the return you can earn without equity risk. If your mortgage is renewing or you’re carrying debt, the case for a sturdier portfolio gets even stronger—because a market drop plus higher interest costs is a nasty combo.

One stance I’ll take: don’t treat your TFSA like a casino chip

A lot of couples keep their TFSA ultra-aggressive because “it’s tax-free, so let it grow.” That logic is incomplete.

The TFSA’s superpower is flexibility. In retirement, it can act as:

- an emergency fund that doesn’t create taxable income,

- a buffer in down markets (withdraw TFSA instead of selling RRSP at a low),

- a tool to manage income thresholds (OAS clawback planning).

So yes, growth matters. But having at least part of your TFSA in lower-volatility assets can improve your overall retirement outcome.

Account-by-account: what to hold in TFSA, RRSP, and non-registered

Asset allocation is step one. Asset location (what goes where) is step two—and it can reduce taxes and improve after-tax returns.

TFSA: your flexibility bucket

Good fits for TFSA holdings:

- A mix of equities and conservative assets if you want it as a volatility buffer

- High-growth equities if you have other safe assets elsewhere and won’t need TFSA funds early

If you’re near retirement and all accounts are 90% equities, a practical move is to build your “safe runway” inside the TFSA (or partly inside it) because withdrawals are clean and won’t push taxable income higher.

RRSP/RRIF: think tax brackets and withdrawal timing

RRSPs are tax-deferred, not tax-free. Near retirement, you want to avoid being forced into large taxable withdrawals after a market drop.

Approaches that often work:

- Keep meaningful fixed income here if it supports a steady withdrawal plan

- Use a planned RRSP-to-RRIF strategy and consider smoothing income before age 72

If you’re going to rebalance toward safety, it’s often simplest inside registered accounts because you won’t trigger capital gains.

Non-registered: manage tax drag and liquidity

Non-registered accounts can be tax-efficient with the right assets, but painful if you generate lots of interest income.

Common positioning:

- Equities (eligible dividends/capital gains) are often more tax-efficient here than interest-heavy products

- Keep your short-term cash needs in the right savings vehicle if you’ll need money soon

One caution: selling appreciated positions to de-risk can create capital gains. That’s not a reason to avoid risk management—but it is a reason to do it thoughtfully (over time, or by rebalancing with new contributions/withdrawals).

A retirement-ready rebalancing plan (that doesn’t rely on perfect timing)

If you’re sitting at 90% equities, the goal isn’t to “call the top.” It’s to create a process.

Step 1: Write down your spending needs in three layers

- Must-pay: housing, food, utilities, insurance, basic transportation

- Nice-to-have: travel, hobbies, gifts, dining out

- Legacy: leaving money to kids/charity

Your portfolio should protect the must-pay layer first.

Step 2: Build a 3-part structure

A clean framework is:

- Cash (0–12 months): bills, emergencies, planned big expenses

- Stability (1–5 years): GIC ladder and/or high-quality bonds

- Growth (5+ years): diversified equities

This matches money to time horizons and reduces panic selling.

Step 3: Rebalance with rules, not feelings

Pick thresholds and stick to them:

- Rebalance when equities drift 5–10 percentage points from target, or

- Rebalance on a set schedule (e.g., twice per year)

This forces you to trim winners and add to laggards—exactly what most people struggle to do emotionally.

Step 4: Stress-test your plan for a bad first year

Run a simple “what if”:

- What if equities fall 25% in your first retirement year?

- How many months/years can you fund spending from safer assets?

- Would you reduce discretionary spending temporarily?

If the answer is “we’d have to sell stocks immediately,” your current risk level is too high for your retirement timeline.

Quick answers to common near-retirement questions

“If we reduce equities, won’t we lose inflation protection?”

You still need growth. The solution is not abandoning equities; it’s right-sizing them and pairing them with a spending buffer. Inflation is a long-term problem. Your first 3–5 years of withdrawals are a short-term problem.

“What if markets keep rising after we de-risk?”

That can happen. You’re buying stability, not bragging rights. A retirement plan that survives downturns is more valuable than one that only looks good in bull markets.

“Should we pay down debt instead of investing more?”

If you’re near retirement with a mortgage renewal coming, paying down high-interest debt can be a risk-free return. Portfolio risk and debt risk stack together. I’d rather see a slightly lower-return plan that’s resilient than a fragile plan optimized for rosy scenarios.

A retirement portfolio should feel a little boring

If your TFSA, RRSP, and non-registered accounts are 90% equities heading into retirement, the fix isn’t fear—it’s structure. Build a safe spending runway, rebalance with rules, and keep equities for what they’re best at: long-term growth.

This is the heart of smart personal finance in an interest rate–uncertain era: align your investments with your cash-flow needs, your debt obligations, and your withdrawal timeline.

If you’re within five years of retirement, take a weekend and map out your first five years of withdrawals. Where will the money come from in a down market? If that answer isn’t crystal clear, your portfolio isn’t retirement-ready yet.