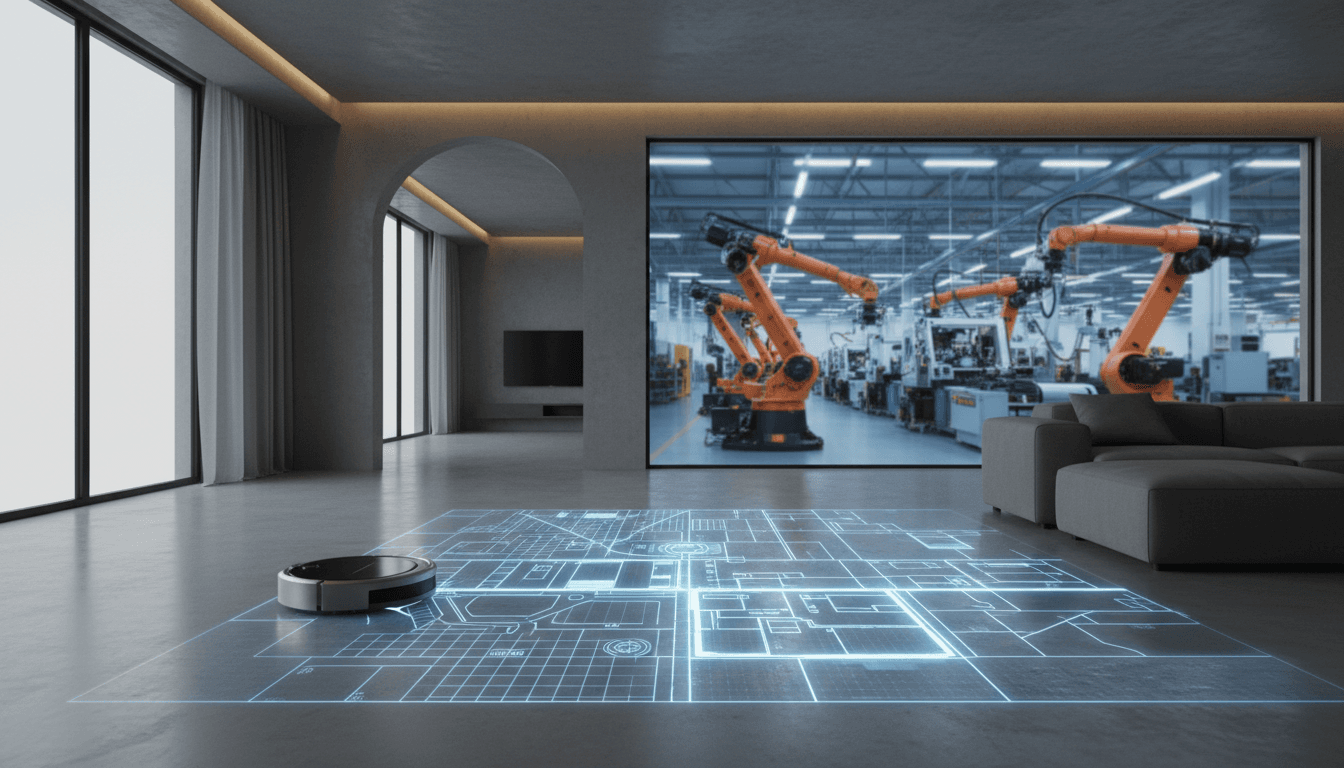

iRobot’s bankruptcy is a warning sign for U.S. robotics. See what it reveals about global competition, regulation, and AI-powered home robots.

iRobot Bankruptcy: What It Signals for U.S. Robotics

A company doesn’t build an iconic consumer robot, help define an entire product category, and then tumble into bankruptcy by accident. Yet that’s exactly where iRobot—the Roomba maker and one of the most recognizable names in home robotics—has landed this week. The company filed for bankruptcy and will hand over its assets to its Chinese manufacturing partner, Picea.

If you work anywhere near AI and robotics—whether you’re evaluating warehouse automation, rolling out autonomous mobile robots, or building the next generation of embodied AI—this isn’t just “sad tech news.” iRobot’s bankruptcy is a case study in how global competition, capital intensity, regulation, and platform power collide in robotics.

And the uncomfortable takeaway is this: the U.S. can still lead in robotics innovation, but the playbook most robotics companies have relied on is getting riskier.

iRobot’s bankruptcy wasn’t sudden—it was delayed

The bankruptcy announcement feels abrupt, but the operational decline has been visible since the Amazon acquisition attempt collapsed.

Back in August 2022, iRobot agreed to be acquired by Amazon for US $1.7 billion. That number mattered: it wasn’t just a payday, it was the kind of capital event that could have funded a multi-year push into more capable home robots—robots that do more than vacuum.

Regulators in the U.S. and Europe opposed the deal, largely due to concerns that Amazon could use marketplace dominance to harm competition. By late January 2024, the deal fell apart. iRobot then:

- Laid off roughly a third of its staff

- Suspended significant R&D investment

- Saw CEO and cofounder Colin Angle exit

From there, iRobot drifted—releasing products, but not projecting the sense of momentum you see when a robotics company has real R&D fuel.

One hard truth about robotics: when serious R&D pauses, the market doesn’t pause with you.

Why this matters beyond robot vacuums

Robot vacuums are often treated as “gadgets,” but they’re also one of the most successful large-scale deployments of autonomous mobile robots in history—millions of units, living in chaotic real-world environments, collecting sensor data, and navigating homes with minimal human input.

That’s the broader theme in our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series: robotics doesn’t fail because ideas are weak. It fails because execution is expensive, global, and political.

The real fight: robotics is a hardware business with software economics

Robotics leaders love to talk like software companies. Investors often want software margins. But embodied AI still runs on atoms: motors, sensors, batteries, plastics, supply chains, testing, returns, customer support, certifications—the whole messy physical stack.

Colin Angle told IEEE Spectrum that by 2020, Chinese robotics companies (with government support) were investing two to three times as much as iRobot in R&D. Whether you agree with every framing in his comments, that ratio aligns with a dynamic many robotics teams feel in practice: competitors who can spend more for longer tend to win the iteration race.

China’s advantage isn’t “just cheap labor”

Most people stop at “lower-cost hardware.” That’s incomplete.

China’s edge in consumer robotics (and increasingly in commercial robotics) comes from a combination of:

- Dense manufacturing ecosystems (components, tooling, QA, logistics)

- Fast iteration loops (build-test-change cycles that happen in weeks)

- Policy support that reduces long-horizon risk for robotics bets

- Domestic scale that rewards aggressive pricing and rapid product refreshes

In categories like home robotics, those factors compound. If one competitor can release meaningful improvements every 6–9 months while another needs 18 months, the “innovation gap” becomes a “market share gap” pretty quickly.

Regulation vs. innovation: the uncomfortable middle

Angle’s view is blunt: iRobot got “roadkilled” by a broader agenda to curb Big Tech. He argues that blocking acquisitions reduces the most common positive outcome for tech startups—being acquired—and that this is destructive for the innovation economy.

I don’t think regulators are wrong to worry about platform power. A dominant marketplace owner buying a device maker that sits inside millions of homes raises real questions. But here’s the part many policy conversations skip:

When you block an acquisition in robotics, you aren’t just blocking a financial transaction. You’re blocking a funding pathway for ongoing R&D in a capital-heavy domain.

That doesn’t automatically mean “approve every deal.” It does mean the analysis has to be specific to robotics realities:

- Does the company have a credible independent path to funding multi-year R&D?

- Are there alternative buyers that keep IP and data governance aligned with local norms?

- What happens to the IP if the company fails after the deal is blocked?

A practical stance for robotics operators and founders

If your strategy assumes, “We’ll get acquired by a mega-platform,” you need a Plan B—now.

In late 2025, the environment is not friendly to large, high-profile acquisitions, and robotics firms are especially exposed because they burn cash to improve reliability and reduce unit cost.

A more durable approach I’ve found is building optionality across three lanes:

- Strategic partnerships that don’t require acquisition (co-development, distribution, joint manufacturing)

- Defense against margin compression (services, consumables, maintenance, fleet management)

- Multiple capital pathways (industrial strategics, project finance, non-dilutive programs where possible)

The data question: home robots are sensors on wheels

One line in the RSS summary should make every product leader sit up: in iRobot’s case, a Chinese company now owns iRobot’s intellectual property and app infrastructure, which may provide access to data from millions of sensor-rich robots in homes.

Roombas and similar devices can collect mapping data, obstacle data, device telemetry, and behavioral signals (when and where cleaning happens). Even if no one is “watching you,” the aggregate dataset is valuable for:

- Improving navigation and perception models

- Training embodied AI behaviors (what households look like in the real world)

- Refining product design (failure modes, wear patterns)

Angle noted that iRobot put serious effort into privacy and security, but he can’t speak to future priorities under new ownership.

What should consumers and enterprises do right now?

This isn’t the moment for panic. It is the moment for basic hygiene.

If you own consumer robots (vacuum, lawn, security, pet, or eldercare devices), do the following:

- Review app permissions (location, microphone, Bluetooth, local network)

- Limit cloud features you don’t use (mapping history, “smart” recommendations)

- Update firmware and set devices to auto-update if you trust the vendor

- Segment your network (a guest VLAN for IoT devices is a practical upgrade)

If you deploy robots in a business setting (retail, hospitality, warehouses, hospitals), add vendor-change scenarios to your risk plan:

- What happens to your data retention policy if ownership changes?

- Do you have contractual clarity on data use for model training?

- Can you continue operations if the app platform is altered or discontinued?

In robotics, “who owns the app” increasingly matters as much as “who builds the robot.”

Lessons for AI and robotics leaders: staying competitive in 2026

iRobot’s story is specific, but the pattern is general: AI-powered robotics is becoming a global scale race, and companies need strategies that work when capital is tight and competitors iterate fast.

1) Treat manufacturing as a core competency, not a vendor task

If your product depends on reliability, noise, battery safety, and cost-down cycles, manufacturing isn’t “outsourced.” It’s part of your product.

Robotics leaders should track:

- Time-to-tooling changes

- Failure rate trends by component supplier

- Unit economics across product generations

When those numbers are opaque, you lose the ability to respond quickly.

2) Protect your differentiator: autonomy that improves over time

Consumers don’t pay more for “AI” as a label. They pay for outcomes: fewer stuck events, better cleaning patterns, smarter obstacle handling, and lower maintenance.

The most defensible robotics advantage is compounding autonomy: every deployed robot makes the system better—without compromising privacy.

This is where the industry is headed:

- On-device perception for sensitive signals

- Federated learning approaches where feasible

- Clear user controls for data collection and retention

3) Build business models that survive price wars

The robot vacuum market has been squeezed by capable low-cost entrants. That dynamic is spreading to other robotics categories.

To avoid becoming a pure hardware margin fight, leaders are moving toward:

- Subscription maintenance and consumables

- Extended warranties tied to predictive diagnostics

- Premium autonomy features (where they deliver obvious value)

- Fleet analytics for commercial deployments

It’s not about squeezing customers. It’s about funding the long-term engineering required to keep robots safe, reliable, and improving.

4) Assume policy will shape your roadmap

Regulatory risk is now a product risk.

If your growth plan depends on acquisition, marketplace distribution, or access to sensitive environments (homes, hospitals, critical infrastructure), treat policy like a first-class constraint:

- Run “blocked deal” scenarios

- Diversify routes to market

- Invest early in privacy, security, and auditability

What iRobot’s collapse should trigger next

It’s easy to frame iRobot’s bankruptcy as a corporate tragedy—and it is. iRobot helped set expectations for what consumer robots could be. It also built robots like PackBot that saved lives. That kind of legacy matters.

But as a business signal, this moment is more useful than sentimental. Robotics is entering an era where the winners combine embodied AI progress with capital endurance, manufacturing speed, and regulatory foresight. If one of the category-defining robotics brands can end up handing assets to a manufacturing partner, everyone should rethink what “moat” means.

If you’re building or buying AI-powered robotics in 2026, ask your team one forward-looking question: If global competition intensifies and regulations tighten, what part of our robotics strategy still works—and what breaks first?