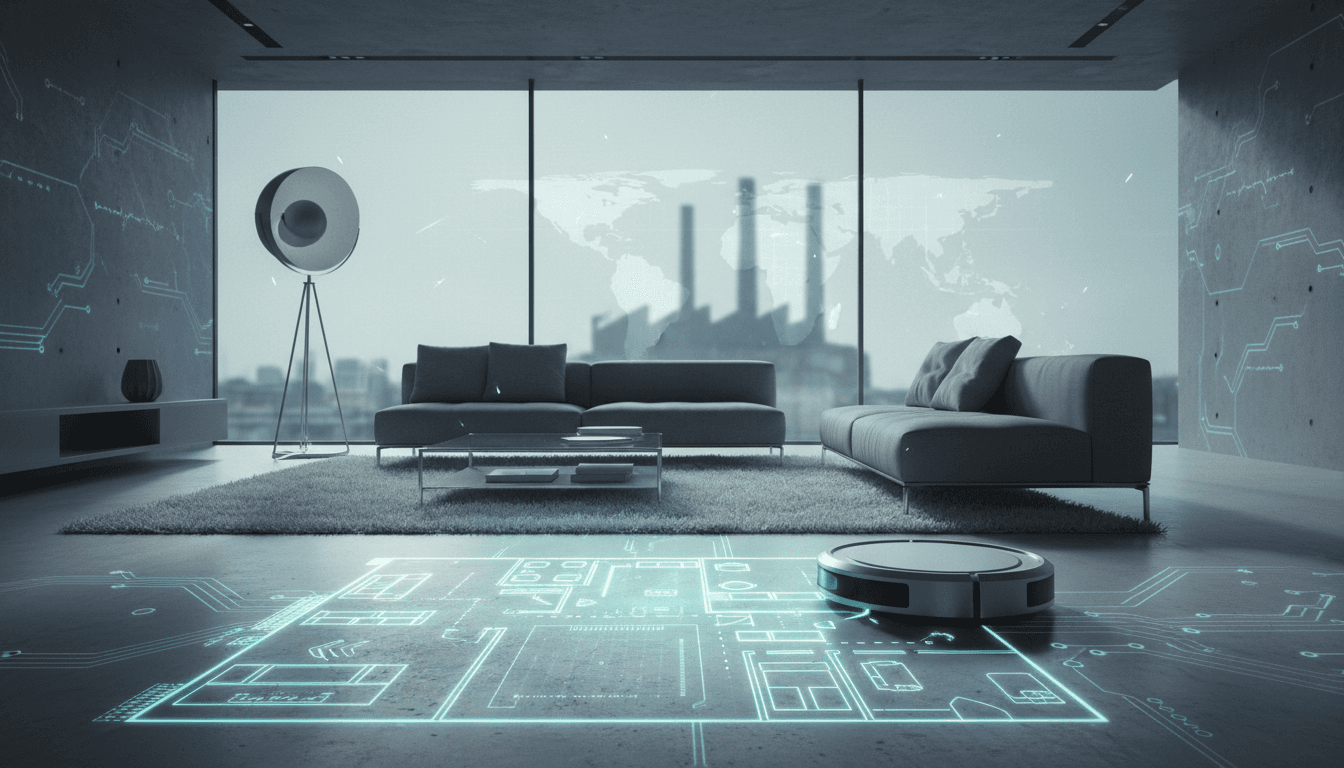

iRobot’s bankruptcy is a warning for AI robotics leaders: scale, R&D funding, regulation, and data governance now decide who survives.

iRobot Bankruptcy: A Wake-Up Call for Robotics

iRobot didn’t lose relevance because people stopped wanting robot vacuums. It lost relevance because hardware robotics has become a geopolitical and capital-intensive race, and the old playbook—build a great product, win a category, then fund the next wave with steady profits—doesn’t hold up when competitors can outspend you on R&D and outscale you on manufacturing.

On Sunday evening, iRobot (the company behind Roomba) filed for bankruptcy and announced it would hand over its assets to its Chinese manufacturing partner, Picea. If you work anywhere near AI and robotics—consumer devices, warehouse automation, healthcare robotics, field robots—this isn’t just “bad news for a brand you recognize.” It’s a case study in what happens when innovation cycles accelerate, capital costs rise, and policy decisions collide with global competition.

This post is part of our Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide series, and I’m going to take a stance: iRobot’s bankruptcy is a warning shot for every robotics company that assumes strong engineering alone will win.

Why iRobot’s bankruptcy matters beyond robot vacuums

Answer first: iRobot’s bankruptcy matters because it exposes the structural pressures hitting the entire AI robotics industry: shrinking hardware margins, fast follower competition, and strategic vulnerability when manufacturing and supply chains sit outside your control.

Roomba popularized the idea that an autonomous robot could live in your home and do real work. That success created a market… and then that market got crowded. According to iRobot cofounder Colin Angle, by the early 2020s iRobot was no longer dominating robot vacuums—especially in Europe, where he cited market share around 12% and declining. A category iRobot helped invent became a commodity battleground.

Here’s the bigger issue: home robotics is an embodied AI problem, not just a motor-and-suction problem. Mapping, navigation, obstacle avoidance, object recognition, edge inference, and cloud-connected product improvement are now table stakes. When competitors can iterate faster and ship more variations at lower prices, the leader’s advantage erodes quickly.

And this dynamic isn’t limited to vacuums. You see it in:

- Warehouse AMRs competing on fleet software + hardware unit economics

- Retail and hospitality robots competing on reliability and serviceability

- Healthcare robotics competing on regulatory pathways and reimbursement plus manufacturing quality

The lesson: Robotics businesses are systems businesses. If one part of the system (capital, supply chain, policy, distribution) breaks, great engineering won’t save you.

The Amazon deal collapse: regulation, strategy, and unintended consequences

Answer first: the failed Amazon acquisition shows how regulatory risk can become existential for robotics firms that depend on M&A as their most realistic path to scale.

In August 2022, iRobot announced a proposed $1.7B acquisition by Amazon. The strategic logic was pretty clear: Amazon wanted a credible entry point into home robotics, and iRobot needed scale and capital to compete against lower-cost, rapidly improving rivals—many based in China.

Regulators had different priorities. U.S. regulators and the European Commission raised concerns that Amazon could use marketplace power to restrict competition. By January 2024, the deal was off. iRobot reportedly laid off about a third of its staff, suspended R&D, and Angle departed.

Angle’s view (as reported) is blunt: regulators focused on “making a point about Big Tech,” and the company got “roadkilled” by a larger agenda.

You don’t have to agree with every part of that argument to take the practical lesson:

For robotics leadership teams: treat regulation as a core design constraint

Robotics companies often plan for engineering risk, market risk, and supply chain risk—but under-plan for policy risk. If your growth plan relies on one of these, you need a backup:

- Acquisition by a platform company

- Exclusive distribution arrangements

- Marketplace-dependent sales

- Large-scale consumer data flywheels

A pragmatic approach I’ve found works: build a two-track strategy.

- Track A: plan for the “happy path” (deal closes, partnership expands, scale arrives).

- Track B: plan for the “regulators say no” path (how you survive 24 months without the deal).

Track B needs real numbers: cash runway, headcount assumptions, product roadmap triage, and a manufacturing plan that doesn’t implode under margin pressure.

Global robotics competition: capital, manufacturing, and speed

Answer first: the hard truth is that robotics is now a scale game, and China’s advantages in manufacturing and coordinated investment make it brutally difficult for under-capitalized players to keep up.

Angle noted that by around 2020, China had become the largest robot vacuum market and that Chinese robotics companies—with government support—were investing two to three times what iRobot could in R&D. Whether the exact multiple varies by firm, the structural point stands: when competitors can fund more experiments, they can ship more product generations, and they can tolerate thinner margins while they learn.

This is the part that a lot of business leaders underestimate: AI robotics R&D isn’t a one-time spend. It’s continuous. Models, sensors, compute budgets, mapping pipelines, SLAM improvements, simulation environments, edge optimization, and QA cycles all compound.

The “hardware flywheel” is different from the software flywheel

Software companies talk about compounding advantages—more users, more data, better product. Robotics has that too, but it’s constrained by physics and cost:

- Every shipped robot creates real-world data, but also creates warranty exposure.

- Every sensor upgrade improves perception, but raises BOM cost.

- Every new SKU expands the market, but increases support complexity.

If a competitor can manufacture at lower cost and iterate faster, they can run more turns of the flywheel.

What U.S. and EU companies can do (that isn’t wishful thinking)

“Compete on innovation” is not a strategy by itself. The companies that keep standing tend to do a few specific things:

- Pick one wedge where they’re meaningfully better (reliability, safety certification, service model, or integration into enterprise workflows)

- Design for manufacturability from day one (not after the prototype works)

- Treat supply chain as a strategic asset (dual sourcing, tooling control, test fixtures, firmware provisioning)

- Invest in simulation and data operations (so learning scales faster than headcount)

If you’re building embodied AI products, you’re not just competing on features—you’re competing on the rate at which you can ship improvements without breaking quality.

Data, privacy, and the “sensorized home” problem

Answer first: when robotics assets and app infrastructure change hands, consumer robot data governance becomes a board-level issue, not a footnote in a privacy policy.

One under-discussed part of the iRobot story is what happens to the ecosystem: the robots, the app, the cloud services, and the data they touch. Angle said iRobot put substantial effort into privacy and security while he ran the company, but he can’t speak to what new owners will prioritize.

That’s not a Roomba-only concern. Home robots are among the most “sensorized” consumer devices people invite inside:

- Room layout and mapping data

- Usage patterns (when people are home, what rooms are used)

- Potentially images or depth data (depending on model and settings)

Practical advice for robotics teams shipping connected products

If you’re selling AI-powered robots—consumer or enterprise—here are governance moves that reduce risk and help sales cycles:

- Minimize data collection by default. If you don’t collect it, you don’t have to defend it.

- Separate identity from telemetry wherever possible.

- Provide clear retention controls (30/90/365 days) and deletion flows that actually work.

- Design “offline-capable” core functionality so customers aren’t forced into cloud dependency.

- Document your security model in plain language for procurement teams.

This matters because trust is becoming a differentiator in robotics. In 2026 budgets, many organizations are tightening vendor assessments, especially for devices that move through physical space.

What iRobot’s fall teaches robotics leaders (actionable playbook)

Answer first: iRobot’s bankruptcy highlights five moves robotics companies should make now: secure capital strategy, protect supply chain control, prioritize fast learning loops, plan for regulatory outcomes, and build defensible trust.

Here’s a practical checklist you can use in a leadership meeting.

1) Don’t confuse brand leadership with technical moat

Brand helped iRobot for years, but competitors closed the feature gap. Your moat needs to be explicit:

- Patents that are enforceable

- Proprietary datasets that improve autonomy

- Distribution advantage you can keep

- Service network and repair ecosystem

2) Build an R&D budget that matches the market’s pace

If competitors are shipping meaningful updates every 6–12 months, a slow roadmap is a quiet failure. Tie R&D spend to:

- Release cadence

- Field learning velocity (bug → fix → rollout)

- Hardware iteration cost per cycle

3) Own the parts of the stack that determine survival

If you don’t control your tooling, testing, firmware provisioning, and key component sourcing, your “product strategy” is partly a negotiation with someone else.

4) Treat M&A as optional, not required

If acquisition is your only route to scale, you’re betting the company on politics. Have a path that works without it:

- OEM partnerships

- Enterprise vertical focus with higher margins

- Subscription/service revenue that improves unit economics

5) Turn privacy and security into a sales asset

Robotics buyers increasingly ask, “Where does the data go?” A strong answer can shorten deals.

A connected robot is a moving sensor platform. Treat it like critical infrastructure, even if it’s a vacuum.

Where this goes next for AI and robotics

iRobot’s story fits the bigger theme of this series: AI and robotics are transforming industries, but the winners won’t be decided by clever demos alone. They’ll be decided by who can scale manufacturing, sustain R&D, ship reliable autonomy, and operate within (or influence) regulatory realities.

For business leaders evaluating automation—whether it’s home robotics, warehouse robots, or embodied AI assistants—this is the question to ask vendors and internal teams: What happens if the market gets 30% cheaper in 18 months, and a regulator blocks your primary growth strategy? If there’s no credible answer, the plan isn’t durable.

If you’re building or buying robotics right now and want a second set of eyes on your autonomy roadmap, data governance posture, or scale strategy, that’s exactly the kind of work we support in this series: turning AI robotics ambition into operational reality.

What would change in your robotics strategy if you assumed—starting this quarter—that hardware competition will intensify and policy risk will increase, not decrease?