Queen City Forward shows how transparent, community-led planning can reshape the Kensington Expressway—and strengthen housing and mobility outcomes in Buffalo.

Queen City Forward: Building Trust Into Buffalo’s Next Highway

A single number explains why the Kensington Expressway conversation can’t stay theoretical: 75,000 vehicles a day use the corridor, according to NYSDOT’s early project framing. When you’re talking about traffic volumes at that scale, decisions ripple far beyond a few on-ramps—into air quality, neighborhood connectivity, housing stability, and local business activity.

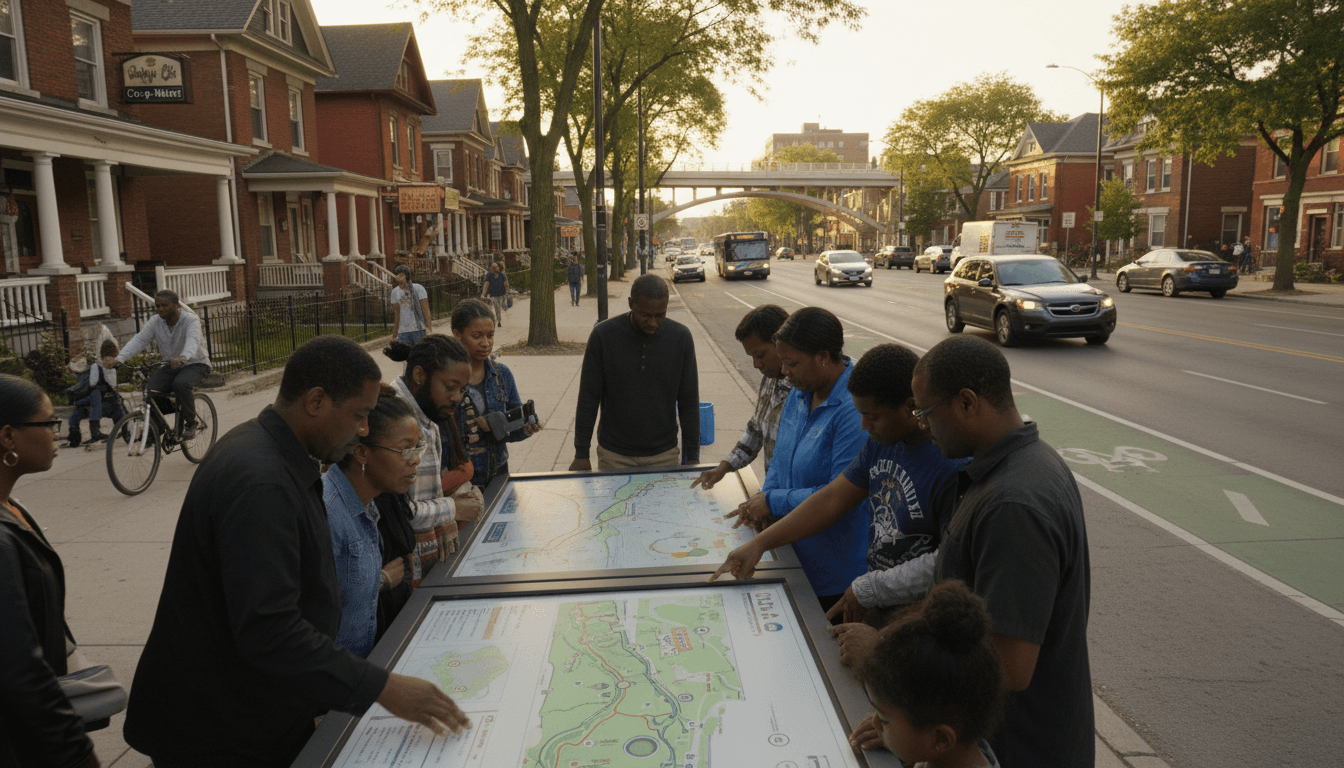

That’s why NYSDOT’s new Queen City Forward website matters more than “another project page.” It’s a signal that the state is trying to rebuild something many transportation projects have historically lacked: public trust. And in the Housing & Infrastructure Development series, this is exactly the point we keep coming back to—modern infrastructure isn’t just concrete and steel; it’s also the process that determines who benefits, who bears the costs, and whether a city can grow without leaving people behind.

Queen City Forward is a “process reset”—and that’s the real story

Answer first: Queen City Forward is designed to restart public engagement around the future of the Kensington Expressway, using a dedicated website and listening sessions to gather input before key decisions harden.

NYSDOT is calling Queen City Forward “a complete reset of the public process,” and I think that phrasing is doing a lot of work—in a good way. Communities across the U.S. have learned the hard lesson that when transportation agencies show up after major decisions are effectively made, public meetings become performative. People sense it immediately.

A reset implies something different:

- Start with lived experience, not a pre-selected solution.

- Make information easy to find (and update it frequently).

- Create multiple ways to participate beyond a single night in a gymnasium.

The new website is positioned as a one-stop hub: outreach schedules, contact options, an FAQ, email updates, and project news. That sounds basic, but “basic” is exactly what builds credibility. If residents can’t quickly answer, “What’s happening, when, and how do I weigh in?” the process fails before it begins.

A transportation project can’t claim to serve the public if the public can’t easily follow it.

Why the Kensington Expressway conversation is also a housing conversation

Answer first: Highway redesign affects housing outcomes because it changes noise and pollution exposure, neighborhood walkability, land values, and the feasibility of new development.

In housing and infrastructure development, we often talk about supply—units built, permits issued, affordability targets. But transportation projects quietly shape the housing market every day.

Connectivity isn’t an abstract value—it changes daily life

When a major expressway cuts through a neighborhood, it can:

- Reduce walkability to schools, jobs, parks, and clinics

- Increase vehicle dependency, pushing household transportation costs up

- Make small commercial corridors less viable because foot traffic drops

When connectivity improves, the benefits don’t just show up in commute times. They show up in whether a neighborhood feels livable and investable—and whether long-term residents can stay.

Air quality and public health are part of the scope, not a footnote

NYSDOT has indicated that early analysis will include air quality effects, alongside traffic study work that contemplates a potential “fill-in” option and diversion impacts. That’s the right direction, but residents should push for specifics: what will be measured, where monitors or models are focused, and how results will shape the alternatives.

If you care about housing stability, you should care about air quality. Poor environmental conditions can depress property values in some blocks, inflate healthcare burdens, and make it harder for families to thrive.

The “success” metric isn’t just traffic flow

A modern transportation project should be judged on more than Level of Service. Real success includes:

- Reduced exposure to harmful pollutants for nearby residents

- Safer crossings for pedestrians and cyclists

- Better access to jobs and services without requiring a car

- Support for neighborhood-scale reinvestment that doesn’t trigger displacement

That last point—displacement—is where process matters most.

What the new Queen City Forward website does right (and what to watch)

Answer first: The website creates a central public record of engagement and project updates; the key risk is whether it stays current and whether feedback visibly changes outcomes.

A dedicated project hub can improve transparency, but only if it’s run like a living product rather than a static brochure.

What’s strong about the approach

Based on NYSDOT’s description, the site includes elements that are genuinely useful:

- Listening session schedule plus future meeting updates

- A clear way to contact project staff and find the outreach office

- Email updates and stakeholder alerts so residents aren’t forced to “check back” manually

- A centralized FAQ for goals, history, and next steps

For large infrastructure planning, that’s not small. It reduces information asymmetry—one of the biggest reasons communities feel shut out.

What residents and stakeholders should expect next

Here’s the litmus test I use: Can an ordinary resident point to where their input went? A credible engagement site eventually shows:

- What we heard (summarized themes, not cherry-picked quotes)

- What we’re studying (specific analyses tied to public concerns)

- What changed (design or scope adjustments, with rationale)

If the site evolves in that direction, Queen City Forward becomes more than outreach—it becomes accountability infrastructure.

Listening sessions: how to make your input actually land

Answer first: The best public comments are specific, local, and measurable—focused on problems, tradeoffs, and success criteria, not just preferences.

NYSDOT scheduled open-house listening sessions in early December, including a second session held mid-month at a community center on Bailey Avenue. Even though those specific dates are now in the rearview mirror (it’s late December), the format is likely to continue—more meetings, more opportunities, more outreach.

If you attend a future session or submit feedback online, here’s what tends to carry weight.

Use “problem statements” instead of solution demands

Agencies can sometimes dismiss a preferred solution as impractical. They can’t easily dismiss a well-documented problem.

Examples:

- “Crossing points feel unsafe at these intersections during school arrival times.”

- “Truck noise spikes overnight between these hours.”

- “Bus stops here lack lighting and ADA-friendly access.”

Ask for measurable success criteria

If you want the project to improve quality of life, define what that means.

Ask NYSDOT to report (by alternative) metrics such as:

- Changes in estimated pollution exposure near homes and schools

- Traffic volumes on neighborhood streets if diversion occurs

- Crash risk predictions for pedestrians and cyclists

- Average travel time reliability at peak periods

Name the tradeoffs you’re willing (and not willing) to accept

Projects get stuck when everyone wants “all upside, no downside.” Honest engagement acknowledges constraints.

Useful comments sound like:

- “I can accept a longer commute if it measurably improves air quality near residences.”

- “I support reconnecting streets, but I want a clear plan to prevent cut-through speeding.”

Put displacement on the agenda early

Transportation upgrades can raise nearby land values. That can be good—unless it prices out current residents.

A strong ask is: coordinate transportation design with housing policy, such as:

- Targeted home repair support for existing homeowners

- Anti-displacement strategies for renters

- Clear plans for how any new developable land benefits the neighborhood

This is where “Housing & Infrastructure Development” becomes real: transport improvements and housing protections have to move together.

A model for modernizing transport networks: transparency as an asset

Answer first: The Queen City Forward approach is a practical template: centralize information, keep feedback visible, and treat engagement as an ongoing system.

Across the country, transportation agencies are under pressure to modernize: reduce emissions, improve safety, and address historic harms from highway placement. The projects that move fastest with the least backlash aren’t the ones with the flashiest renderings—they’re the ones that build a durable coalition.

Queen City Forward hints at a playbook other regions should copy:

- Single source of truth: one hub where the public can track progress

- Many on-ramps to participation: meetings, digital feedback, alerts

- Clarity about studies: traffic, diversion, and air quality work stated upfront

- Consistency: regular updates that don’t disappear after the first wave of press

“Building roads, building trust” isn’t a slogan. It’s project risk management. When people don’t trust the process, timelines slip, costs rise, and outcomes degrade.

What you can do this week if you care about Buffalo’s transportation future

Answer first: Subscribe, submit one specific concern, and recruit two neighbors—engagement scales when people share the workload.

If Queen City Forward is going to reflect Buffalo’s needs, participation can’t be limited to the same handful of voices (even well-intentioned ones). Broad input is how you get a design that works for commuters and residents living closest to the corridor.

Here’s a practical, low-friction checklist:

- Sign up for project updates so you don’t miss meeting windows.

- Submit one location-specific issue (an intersection, a block, a time-of-day problem).

- Bring a neighbor’s perspective—especially someone who walks, uses transit, or drives for work.

- Ask for the “what we heard / what changed” loop to be published and updated.

The big question hanging over Buffalo’s next chapter is simple: Can a major transportation project improve mobility while also repairing neighborhood connections and protecting housing stability? Queen City Forward is a chance to prove the answer can be yes.