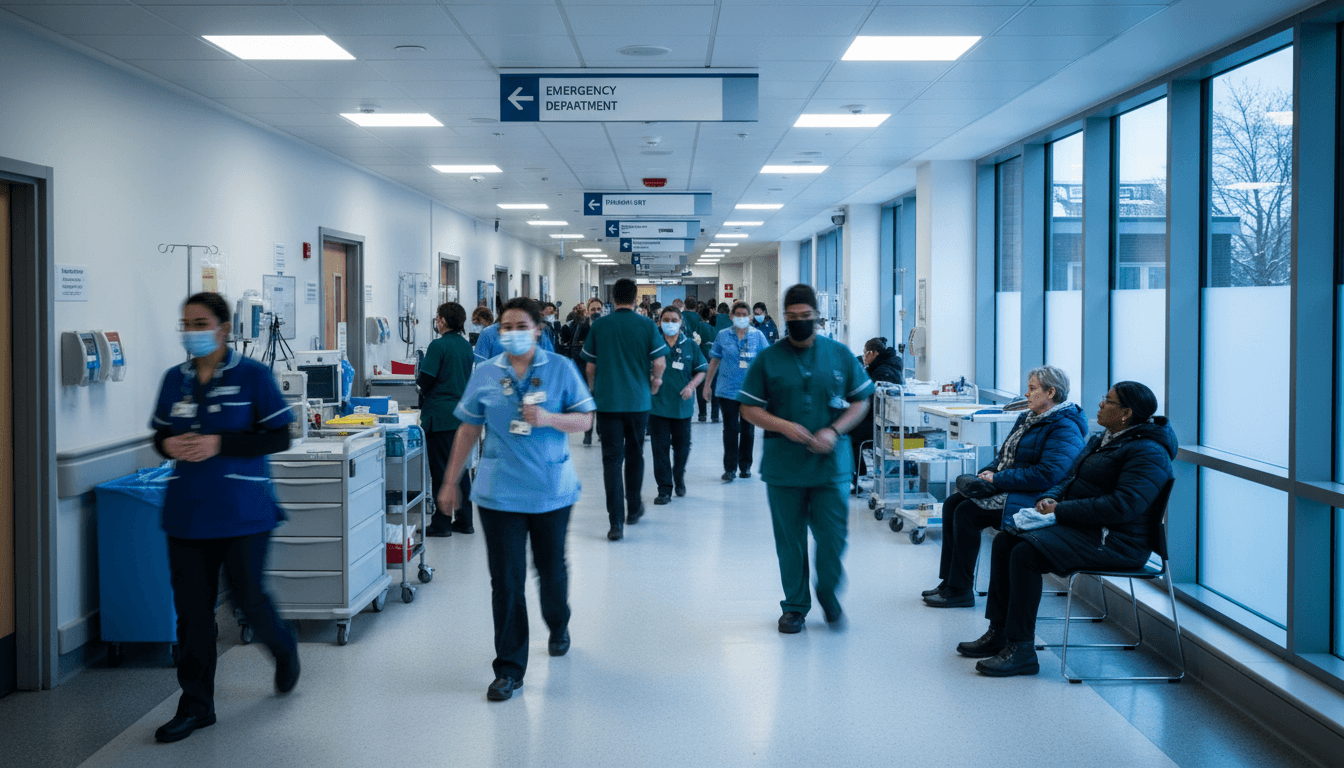

Flu admissions are up 55% and A&E demand is at a record. Here’s what the NHS data says about capacity, modernisation, and urgent reform.

Winter Flu Surge: What NHS Data Reveals About Reform

Flu hospitalisations in England jumped 55% in a single week, reaching an average of 2,660 flu patients per day in hospital beds—the highest ever for this time of year. Add a 35% rise in norovirus inpatients (to 354 per day), record A&E attendances in November (2.35 million), and 802,525 ambulance incidents in the same month, and you get what NHS leaders are calling a “worst case scenario” December.

This isn’t just a bad week. It’s a stress test the NHS faces every winter—only now it’s happening alongside a scheduled resident doctors’ strike (17–22 December) and a public that’s already anxious about access, delays, and overcrowded hospitals.

As part of this Healthcare & NHS Reform series, I want to be blunt: winter virus surges don’t have to translate into system-wide crisis. The data in this update doesn’t only describe pressure—it points to where modernisation and capacity planning can actually work. The NHS has already proven it can move fast (vaccinations, record testing volumes). The question is whether we’ll turn that capability into a lasting redesign.

What the “super flu” numbers are really telling us

The headline statistic—2,660 flu patients per day—matters because hospital beds are a fixed resource on the day. When thousands of beds are occupied by preventable respiratory illness, everything else backs up: elective surgery, discharge flow, ambulance handovers, and ED waiting times.

Here’s the key point: a flu surge isn’t only a public health problem; it’s a capacity problem.

If you’re looking at NHS reform through a practical lens, this is the chain reaction policymakers and healthcare leaders need to plan around:

- More flu and norovirus admissions → fewer available beds

- Fewer beds → ED boarding and delayed admissions from A&E

- Congestion in A&E → ambulances waiting to offload

- Longer ambulance handovers → slower community response times

- Slower response times → higher clinical risk, more complex admissions

Even when performance improves in one area (for example, the NHS reported Category 2 ambulance response times at 32 minutes 46 seconds, nearly 10 minutes faster than October 2024), the whole system can still feel broken if hospital flow is jammed.

Norovirus is the quiet multiplier

Flu gets the attention, but norovirus is often the operational nightmare. It spreads quickly, affects staff and patients, and can force bay closures for infection control. A 35% rise in norovirus inpatients isn’t just “more sick people”—it can mean less usable estate, even if the building technically has the same number of beds.

For reform, that points to a simple reality: infection control capacity is capacity. You can’t run hospitals at the edge year-round and expect resilience when wards need isolating.

A&E and ambulance records: demand is outpacing the model

The NHS reported 2.35 million A&E attendances in November, a record, and 802,525 ambulance incidents—48,814 more than last year. That’s a demand curve that keeps bending upward.

The uncomfortable truth: we’re still running a 2025-level demand profile through pathways designed for a different era. When more people seek urgent care—often because routine access is hard or symptoms escalate—the front door becomes the default. The system then pays a higher price later (admissions, longer stays, worse outcomes).

“Just don’t go to A&E” isn’t a strategy

Public messaging helps—people should absolutely use 111 online for urgent but non-life-threatening needs during industrial action and winter surges. But reform can’t rely on hoping the public triages perfectly.

A modern urgent care model should make the right choice the easy choice:

- Same-day urgent slots in primary care that are actually available

- Direct booking from 111 into urgent treatment centres, GP out-of-hours, and rapid assessment units

- Clinical navigation that routes patients based on risk, not just symptoms

- Real-time capacity visibility so the system stops sending everyone to the same crowded sites

If the NHS wants fewer unnecessary attendances, it needs to outcompete A&E on speed and certainty for low-acuity problems.

Vaccination is working—so why are we still in crisis?

This update includes a bright spot: 17.4 million people have had flu vaccination so far this season, 170,000 more than this time last year. Even NHS staff uptake improved, with 60,000 more frontline healthcare workers vaccinated compared to last year.

That’s real progress. But it also exposes a gap in how we think about prevention.

Prevention can’t be a seasonal campaign; it has to be a system capability

The NHS did the hard work of vaccinating at scale. Now the question becomes: how do we turn “more jabs” into “fewer admissions” reliably every winter?

A few reform-minded moves that are practical (not theoretical):

-

Target the right groups with precision

- Use local data to focus on care homes, clinically vulnerable groups, and areas with historically low uptake.

- Don’t just offer vaccination—chase completion.

-

Make access frictionless

- Expand walk-in and pop-up clinics in high-footfall locations.

- Offer predictable evening/weekend capacity in December (when immunity still matters for late-season peaks).

-

Treat workforce vaccination as operational readiness

- High staff vaccination rates reduce staff absence and preserve safe staffing.

- This is as much about service continuity as it is about personal protection.

Vaccination is the cheapest capacity expansion you can buy. It won’t remove winter pressure, but it can shrink the peak.

Strikes plus winter demand: the system needs “continuity design”

The scheduled resident doctors’ strike (17–22 December) compounds risk because it hits during an already volatile period. The NHS is advising patients to attend planned appointments unless contacted, and to use 111 online for non-life-threatening issues.

There’s a wider reform lesson here: industrial action will happen again at some point, whether in medicine, nursing, or another part of the workforce. A resilient NHS needs continuity designs that reduce harm when capacity drops unexpectedly.

What “continuity design” looks like in practice

This is where modernisation stops being a buzzword and becomes operational.

- Ringfenced urgent diagnostics: protect imaging and lab capacity for emergency and time-critical decisions.

- Standardised clinical prioritisation: reduce variation in what gets cancelled and what gets protected.

- Digital rebooking at scale: if an appointment is moved, the patient should get a new slot quickly—without hours on the phone.

- Virtual wards and remote monitoring: keep suitable patients safely at home with escalation pathways.

The goal isn’t to “operate as normal” during disruption. The goal is to protect outcomes and reduce knock-on backlogs.

What NHS modernisation should focus on (so winters stop breaking it)

If this winter feels like the same story with higher numbers, it’s because the bottlenecks are persistent. The reform agenda needs to be unglamorous and specific.

1) Bed capacity that reflects infection reality

Hospitals need enough flexibility to manage isolation requirements without collapsing flow.

That can mean:

- more single rooms in rebuilds and refurbishments

- surge plans that don’t depend on unsafe corridor care

- discharge capacity that’s properly funded and coordinated with social care

2) Flow, not just funding

You can add money and still get gridlock if patients can’t move through the system.

A flow-first approach prioritises:

- early senior clinical decision-making

- rapid assessment models that avoid unnecessary admission

- discharge planning starting on day one

- community step-down options (including reablement and intermediate care)

A line I keep coming back to: a hospital bed is the most expensive waiting room in the country. The system should treat avoidable bed-days as a reform emergency.

3) Tech that removes work, not adds clicks

Modernising healthcare delivery means choosing technology that reduces administrative load and improves routing.

Practical examples that matter in winter:

- 111 that can book directly into local services

- shared care records that prevent repeat history-taking and duplicate tests

- real-time dashboards for bed state, ambulance handover delays, and staffing gaps

If digital tools don’t save clinician time, they aren’t modernisation—they’re just extra tasks.

4) Primary care capacity that keeps people out of hospital

The government has highlighted recruitment of 2,500 more GPs and improvements to GP appointment booking. That’s the right direction, because keeping patients cared for in the community is the highest-leverage move.

But access improvements must be felt by patients:

- faster clinical triage

- more same-day options for acute illness

- structured long-term condition reviews to prevent deterioration

When primary care is hard to reach, A&E becomes the safety net. When primary care is responsive, hospitals breathe.

What you can do right now (and why it helps reform, not just this winter)

Big system redesign takes time. But winter pressure is immediate. Here are actions that reduce risk now and support NHS resilience longer-term:

- If you’re eligible, get the flu vaccine this week. Immunity timing matters before Christmas gatherings.

- Use 111 online for urgent, non-life-threatening issues to get directed to the right service.

- Keep A&E for life-threatening conditions and serious injuries. That protects capacity for strokes, sepsis, heart attacks, and major trauma.

- If you’re an employer or community leader, promote vaccination and sensible sick policies. Presenteeism fuels spread.

These aren’t small gestures when the numbers are this high. Fewer infections equals fewer admissions equals more capacity for cancer care, surgery, and urgent emergencies.

The reform question this winter forces us to answer

The NHS is facing a December where flu, norovirus, record urgent demand, and industrial action collide. The immediate response—vaccination pushes, 111 triage, keeping emergency care available—is necessary.

But the bigger lesson is sharper: winter pressure isn’t a surprise; it’s a predictable stress event. A modern NHS should be built to absorb it without tipping into crisis.

If you’re involved in healthcare leadership, commissioning, digital health, estates planning, workforce strategy, or community services, this is the moment to get practical: focus on flow, prevention, and operational resilience. If you’re a patient or carer, the most powerful contribution is still prevention—vaccination and smart service use.

Next winter will come just as reliably as this one. The real question is whether we’ll still be calling it a “worst case scenario”—or whether NHS modernisation finally makes it a manageable surge.