NHS England warns adult breathing circuits can be misassembled without a safe exhalation route. Here’s how to standardise checks and training within 6 months.

Breathing Circuit Safety: Stop Exhalation-Route Errors

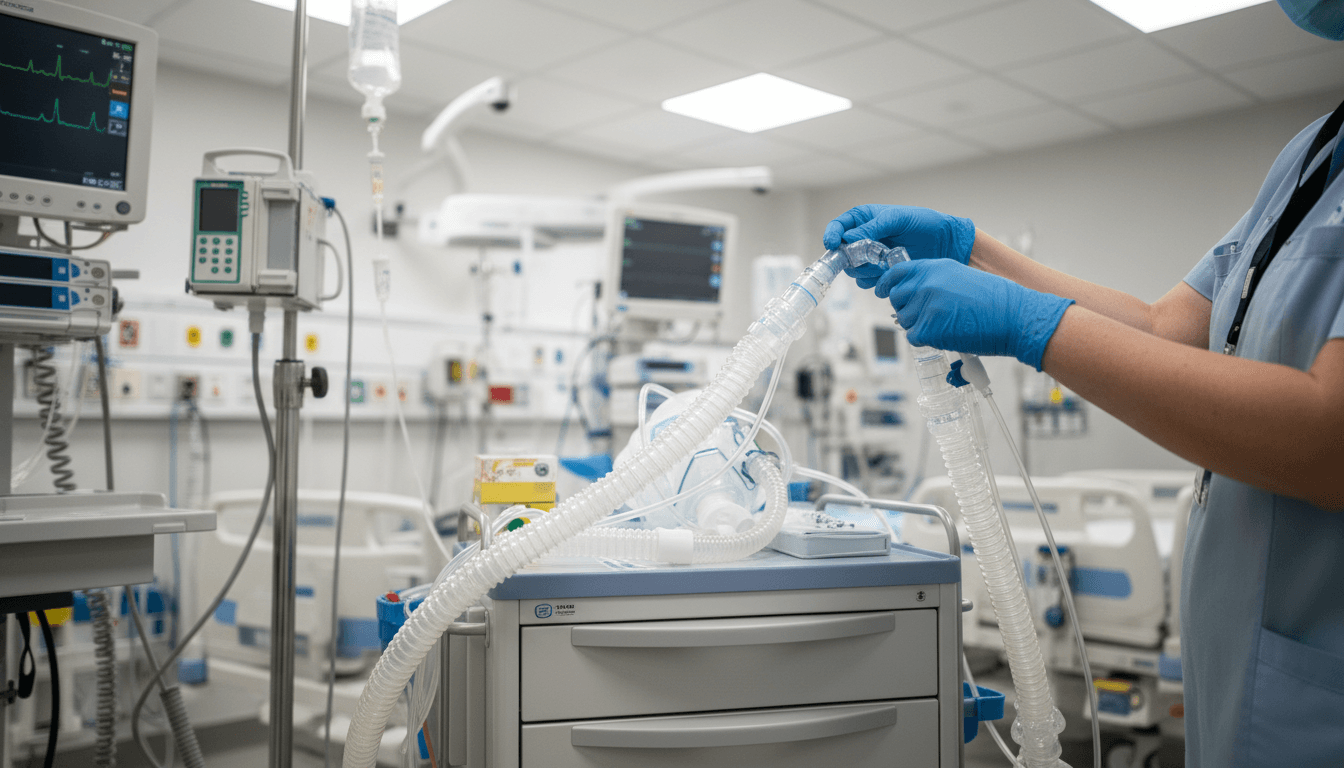

A breathing circuit that doesn’t allow a patient to exhale properly is a quiet kind of danger. It can look “connected,” the ventilator can look “on,” and yet the setup can still be wrong in a way that threatens life within minutes.

That’s why NHS England has issued a national patient safety alert on the risk associated with adult breathing circuits lacking a patent (open) exhalation route—after reports of patients being harmed or exposed to potential harm due to incorrect assembly. The alert isn’t just a technical note for ICU teams. It’s a test of whether we can modernise respiratory care in a way that genuinely improves patient safety and NHS capacity.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: standardising how we assemble, check, and teach breathing circuits is one of the simplest high-impact reforms available. It’s not glamorous, but it prevents avoidable deterioration, emergency escalation, and the downstream bed-blocking that follows.

What the NHS alert is really saying (and why it matters)

The core message is direct: patients have been harmed because breathing circuits were incorrectly assembled, resulting in no effective exhalation route for invasive or non-invasive ventilatory support.

The required actions are also clear. NHS organisations caring for patients using invasive and non-invasive breathing circuits must:

- Create local guidance and visual aids for assembly and connection of breathing circuits

- Implement training that includes specific safety checks

- Establish a clear process for communicating updates to that guidance

- Complete all actions within 6 months

This matters beyond compliance. When ventilatory support goes wrong, the cost isn’t only clinical—it’s operational:

- One preventable deterioration can trigger an emergency response, ICU admission, or prolonged stay.

- One avoidable ventilator incident can remove capacity from elective recovery, urgent admissions, and winter escalation pathways.

In a “Healthcare & NHS Reform” context, this is exactly the kind of system-level safety work that reduces pressure on the front door by preventing avoidable harm on the wards.

How a blocked exhalation route harms patients

At the simplest level: ventilation must allow flow in and flow out. If exhalation is obstructed or the circuit is assembled without a functioning exhalation path, pressure can build in the system.

The clinical risk in plain English

If a patient can’t exhale effectively, several things can happen quickly:

- Air trapping and rising airway pressures

- Inadequate ventilation (carbon dioxide retention) and worsening acidosis

- Rapid deterioration that looks like “the patient is getting worse,” when the real issue is the setup

- Increased need for escalation (higher oxygen, intubation, ICU transfer)

For non-invasive ventilation (NIV), the risk can be even more deceptive because teams may assume masks and circuits are “plug-and-play.” They aren’t. NIV circuit configuration varies by device, vent mode, and interface type.

Why this failure mode keeps happening

Most companies get this wrong: they treat equipment safety as a one-off training tick-box.

But circuit assembly errors persist because:

- Staff rotate rapidly (bank, agency, redeployed teams, trainees)

- Different wards use different ventilators and circuits

- Consumables change due to procurement shifts and stock pressure

- Under time stress, people copy what’s nearby—even if it’s incorrect

The reality? Complexity plus variation plus time pressure creates predictable failure. Standardisation is how you break that pattern.

Standardisation isn’t bureaucracy—it’s capacity protection

A national patient safety alert can feel like more paperwork. The better lens is this: standardising breathing circuit setup is an NHS capacity intervention.

Every avoidable respiratory incident creates knock-on effects:

- More calls to critical care outreach

- Longer time on higher acuity beds

- More imaging, blood gases, and clinical time spent firefighting

- Potential CQC scrutiny and internal investigation workload

If you care about reducing waiting lists, you should care about this alert. Elective flow relies on predictable critical care and post-op capacity. Patient safety and throughput are the same conversation.

What “good” looks like in practice

“Good” is not a PDF buried on the intranet.

Good looks like:

- One agreed setup per scenario (or a small number, explicitly defined)

- Visual guides at point of use (trolley, ventilator, NIV area)

- Checks embedded into routine workflow (handover, initiation, and step-up/step-down)

- A way to manage change when kit or guidance updates

The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine has also produced a resource to help design local guidance and visual aids. That’s helpful because it pushes teams toward shared language and consistent diagrams, not “everyone draw their own version.”

Turning the alert into a workable local plan (within 6 months)

The alert gives a timeframe. The challenge is execution across busy services.

Here’s a practical approach I’ve found works: treat it like a mini-change programme, not “education.”

1) Map your real-world circuit variants (not the ideal ones)

Start by listing what’s actually in use:

- Invasive ventilation circuits (types and connectors)

- NIV circuits (vented vs non-vented, intentional leak ports, exhalation valves)

- Interfaces (full-face masks, nasal masks, tracheostomy interfaces)

- Humidification and filters (where they sit, what changes when they’re added)

Then identify the high-risk points: where someone can connect “a thing that fits” but creates no patent exhalation route.

2) Create visual aids that reduce thinking under pressure

Visual aids need to work at 3am.

Strong visual aids usually include:

- A single “correct configuration” diagram per setup

- A red-flag panel: “If you see this, stop” (common wrong assemblies)

- A simple exhalation route check: what to look/listen for, and what “normal” looks like

- Clear naming that matches your local stock labels

Keep it brutally simple. If it needs a scroll bar, it won’t be used.

3) Train for the checks that catch the error early

Training that prevents harm is hands-on and scenario-based.

Build short modules around:

- Setting up the circuit from scratch

- Swapping consumables without changing the exhalation path

- Recognising early signs of a missing exhalation route

- Immediate actions if suspected (stop, disconnect safely as appropriate, switch to known-safe configuration, call for senior/critical care support)

If you only do one thing: teach a specific “exhalation route check” and make it mandatory at initiation and at handover.

4) Put ownership where it belongs: named roles and escalation

This work fails when “everyone” owns it.

Make it explicit:

- Clinical owner (ICU/NIV lead clinician)

- Operational owner (matron/ward manager/service manager)

- Education owner (practice educator/clinical skills team)

- Procurement/EBME liaison (because stock changes create new risks)

And define what happens when equipment changes: who updates the visual aid, who retrains, and how fast.

5) Make communication of updates routine, not heroic

The alert explicitly calls for processes to communicate updates.

Practical options:

- A short “kit change bulletin” format used trust-wide

- A QR code on the trolley that points to the current visual (with version/date)

- A monthly respiratory safety huddle item: “Any circuit changes this month?”

This is how you avoid the classic NHS failure: great guidance that becomes wrong six months later.

Common questions frontline teams ask (and straight answers)

“Isn’t this just an ICU problem?”

No. NIV is used across respiratory wards, ED, AMU, and sometimes escalation areas. Transfers between areas are exactly when configuration errors creep in.

“We already do competency sign-offs—why isn’t that enough?”

Because competency sign-off often proves someone can do a task once, in calm conditions, on one device. Safety depends on standardised setups, point-of-care prompts, and repeatable checks across staff groups and shift patterns.

“Won’t standardisation reduce flexibility?”

It reduces unhelpful variation. You can still allow defined exceptions (e.g., tracheostomy circuits, specific ventilator models). The point is that exceptions are named, trained, and visually supported—not improvised.

What this means for NHS reform in 2025–26

Winter pressure, respiratory admissions, and delayed flow don’t leave much slack. When an avoidable ventilatory incident occurs, it doesn’t just harm a patient—it steals time and beds from everyone waiting behind them.

There’s a better way to approach this: treat equipment setup and safety checks as part of service design. The same discipline we apply to theatre checklists and medicines management needs to apply to breathing circuits.

Patient safety isn’t separate from NHS capacity. It’s one of the few levers that improves outcomes and throughput at the same time.

If your organisation is working through this alert now, the most valuable question to ask is simple: when the next new staff member starts on nights, will the safest breathing circuit setup be the easiest one to do?