Modern learning environments shape engagement and workforce readiness. See how school modernization boosts belonging, CTE outcomes, and skills training.

Modernizing Schools to Build Workforce-Ready Skills

A 2020 federal review found more than half of the nation’s 100,000 K–12 schools need major HVAC or plumbing replacements to reduce health hazards. That’s not a facilities footnote. It’s a skills problem.

When the physical environment is noisy, stale, dim, or carved into awkward add-ons, learning takes more effort than it should. Teachers spend energy managing the room instead of teaching. Students read signals—about belonging, status, and what the community thinks they’re “worth”—before they ever open a laptop or pick up a soldering iron.

This post is part of our Education, Skills, and Workforce Development series, and I’m going to take a firm stance: school modernization is workforce development. Not as a metaphor, but as a practical strategy. The story of former teacher-turned-architect Josh Grenier—who watched an arts program move from a basement to a celebrated fine-arts wing—shows how quickly perception, engagement, and identity can change when facilities stop working against learners.

The building teaches, even when nobody means it to

Key point: The design of a school communicates value and shapes student behavior long before instruction begins.

Grenier’s original classroom was in a basement: no windows, poor ventilation, a leftover space that felt like it belonged to the building’s past. The later renovation flipped the script—his students moved from “the worst space to the best space,” and the arts program’s status rose with it.

That’s not just pride. It’s psychology and sociology in action. A school can quietly sort people into “front door” and “back door” experiences. Grenier described a layout where bus riders entered by dumpsters and a loading dock while students who drove cars walked in through the polished front entrance. Even if no one says the quiet part out loud, students understand the hierarchy.

In workforce terms, this is pipeline formation. Students opt into (or out of) pathways partly based on whether they feel those pathways are respected. Put CTE labs in the “temporary” portable buildings for a decade and don’t be surprised when enrollment or persistence stalls.

A practical lens: “signals” are part of equity

If you’re making facilities decisions, ask a blunt question during planning:

- What does a student conclude about their future when they walk into this space?

That single prompt catches dozens of problems—lighting, entrances, visibility of student work, staff collaboration spaces, even where the bathrooms are.

Healthy buildings create capacity for learning—and for skills training

Key point: Indoor air quality, thermal comfort, and acoustics aren’t comfort perks; they’re learning conditions.

When districts postpone mechanical upgrades, they often treat them as invisible infrastructure. But health and performance research has been pointing in the same direction for years: poor ventilation and aging systems correlate with worse cognitive outcomes, higher absenteeism, and higher stress.

Grenier’s comments land on a detail many leaders underestimate: acoustics. Loud, chaotic rooms don’t just annoy people. They raise cognitive load. They make reading comprehension harder. They make confidential conversations with students nearly impossible. If you want strong career counseling, effective special education supports, and calmer classrooms, sound control is a learning intervention.

For workforce readiness, the stakes get even higher in hands-on environments:

- In a fabrication lab, poor ventilation isn’t “unpleasant”—it can be unsafe.

- In health sciences spaces, temperature and air flow affect sanitation and comfort.

- In media production rooms, acoustics determine whether students can produce usable audio.

When we say “modern learning environments,” we should mean the basics are handled: air, light, sound, and safe, code-compliant systems.

The money problem is real—so design has to be smarter

The American Institute of Architects has reported that district spending capacity for renovations has dropped by about $85 billion per year nationwide since 2016. That gap forces tradeoffs.

My opinion: when funding is tight, districts should protect the upgrades that change day-to-day learning friction (HVAC, roofs, plumbing, acoustics, lighting) before chasing cosmetic upgrades. A beautiful commons with a failing HVAC system is a branding exercise, not a learning strategy.

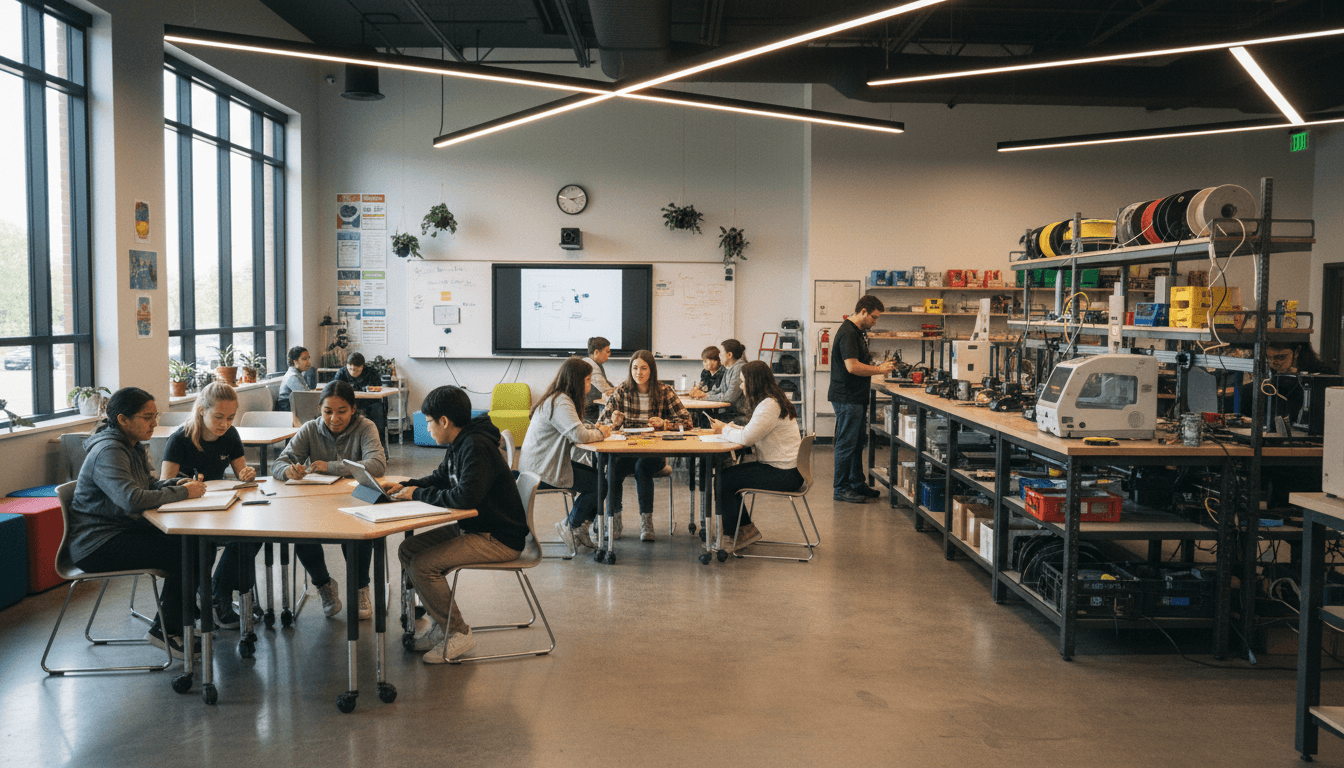

Flexible spaces support modern learners (and modern jobs)

Key point: Flexibility isn’t about trendy furniture; it’s about making one room serve multiple learning modes.

Grenier described designing for the reality that students move through a day filled with independence, small-group work, informal collaboration, and quiet focus—often in the same class period. A room locked into one posture (rows, one focal point, no spillover) works against that.

He also highlighted something districts sometimes dismiss as “extras”: movable furniture, including pieces that support fidgeting. For students with ADHD, anxiety, sensory needs, or simply high energy, the ability to move without disrupting others can be the difference between engagement and escalation.

Here’s the workforce connection that doesn’t get enough airtime: most workplaces now reward context switching and collaboration. Students need practice moving between:

- Individual deep work

- Pair and team problem-solving

- Presenting and explaining decisions

- Quiet reflection and revision

A flexible classroom is basically a rehearsal space for that reality.

A quick checklist for workforce-aligned classroom flexibility

If you’re scoping renovations or selecting furniture, start here:

- At least three zones per room: instruction, collaboration, quiet/reading.

- Clear circulation for backpacks, mobility devices, and quick transitions.

- Power where students work, not only at the teacher wall.

- Writeable surfaces (boards/walls) near collaboration zones.

- Storage that reduces clutter (clutter is a hidden behavior trigger).

None of this requires luxury finishes. It requires intent.

Renovating “Franken-buildings” without breaking your community

Key point: Older schools often become confusing mazes; renovation should simplify movement and strengthen identity.

Post–World War II schools were built for a different era: stable neighborhood enrollment, predictable schedules, fewer specialized programs, and fewer requirements around accessibility and building systems. Over decades, many campuses became what Grenier called “Franken-buildings”—added onto again and again until circulation is confusing and the building feels disorganized.

That matters because navigation is part of safety, belonging, and instructional time. If students are late because the building is a maze, you don’t have a discipline issue—you have a design issue.

In Cañon City, Grenier’s team focused on creating a new “core” that reflected pride in strong CTE programs and connected piecemeal areas into a coherent whole. That approach is worth stealing:

- Start with what’s already excellent (signature programs, community traditions, student achievements).

- Build the plan around that identity, so modernization feels like continuity, not replacement.

People also ask: Should we renovate or build new?

A practical answer: Renovate when the structure can support modern systems and the layout can be simplified. Build new when the building’s bones force permanent compromises.

Three decision factors that cut through politics:

- Mechanical feasibility: Can HVAC, plumbing, and electrical be upgraded without endless patching?

- Program fit: Can you support specialized pathways (CTE labs, arts, health sciences) safely?

- Operational efficiency: Can staff supervise, secure, and maintain the campus without wasting time?

If two out of three are “no,” new construction often becomes the more responsible long-term decision.

Don’t let closed buildings become a blight—treat reuse as workforce strategy

Key point: Repurposing unused school buildings can expand training capacity—if you plan reuse before closure.

Shrinking enrollment in some areas and growth in others is pushing districts toward consolidation. Grenier described a worst-case scenario: a closed school sold without a vetted reuse plan, later abandoned, becoming unsafe and damaging to the neighborhood.

Here’s a better way to frame it for the Education, Skills, and Workforce Development agenda: an underused building is potential training infrastructure. With the right partnerships, former schools can become:

- Adult education and GED centers

- Regional CTE hubs

- Early learning centers (freeing other buildings for upper-grade programs)

- Apprenticeship classrooms with local employers

- Community health and workforce navigation sites

But it only works if districts set criteria and require credible reuse proposals. Selling to “any buyer with a bid” is how you end up with a boarded-up building that costs the community far more than it gained.

A simple reuse screen districts can adopt

Before selling or closing, require proposals to answer:

- What services will operate here in 12 months?

- What funding supports those services for 3–5 years?

- Who is accountable for code compliance and maintenance?

- How will the site be secured and activated after hours?

If those answers aren’t clear, don’t sell yet.

What school leaders can do in 2026 planning season

Key point: You don’t need a bond measure tomorrow to start making smarter facilities decisions.

December is when many districts and colleges are mapping spring budgets, capital plans, and grant calendars. If your goal is workforce readiness, treat facilities like a strategic input—not a separate department.

Here are actions that work even in tight funding cycles:

- Run “student journey” walkthroughs: follow the path of a bus rider, a student with mobility needs, and a student in a CTE pathway. Document what the building signals at each step.

- Audit friction points: where do transitions break down (noise, crowding, bottlenecks, unclear supervision)? Fixing these often has outsized impact.

- Prioritize invisible wins: HVAC, acoustics, lighting, and water systems are unglamorous—and they produce reliable improvements.

- Modernize one pathway space: pick a high-impact program (health sciences, welding, IT, culinary, arts) and upgrade it to be a “show what we value” anchor.

- Invite employers to react to the learning environment: not as donors, but as partners who can tell you whether the space mirrors real working conditions.

Facilities investments are expressions of what a community values. When students feel that value, they show up differently.

The forward-looking question for every district and campus isn’t “How old is our building?” It’s this: Does our learning environment make it easier—or harder—for students to become capable, confident, employable adults?

If you’re planning renovations, expansions, or consolidation, align the physical environment with the outcomes you’re asking educators to deliver. Workforce development doesn’t start at graduation. It starts at the front door.