Global study tours help U.S. school leaders bring proven practices home. See what Finland and Uruguay teach about whole-child learning and digital equity.

Global Study Tours That Improve U.S. School Outcomes

A surprising number of school improvement plans fail for the same reason: leaders only study their own system. When budgets tighten and enrollment drops, that tunnel vision gets expensive fast. Districts end up funding familiar programs instead of proven practices.

Global study tours flip that script. When U.S. school leaders visit places like Finland and Uruguay—and then do the hard work of adapting what they see—they come home with ideas that are both research-backed and implementation-ready. In the Education, Skills, and Workforce Development series, I care about one thing most: whether an idea helps students build the skills they’ll need for what comes after graduation. Global learning does, because it changes what adults do first.

Below, I’ll break down what U.S. districts are learning abroad (with real examples), why it translates into better teaching and stronger career readiness, and how to run an international learning experience that produces results instead of souvenirs.

Why global learning is a budget strategy, not a perk

Global study tours work because they reduce “reinvention costs.” The fastest way to waste scarce dollars is to build a new initiative from scratch when another system has already tested the routines, staffing models, and guardrails.

District leaders are facing a tough math problem: declining enrollment and shrinking budgets mean less flexibility, fewer electives, and more pressure to show measurable outcomes. In that context, international education exchange isn’t about copying another country’s school system. It’s about seeing alternatives you can’t imagine from inside your own constraints.

Here’s the practical payoff:

- Faster decision-making: Seeing a working model clarifies what’s essential versus optional.

- Better questions: Leaders come home asking “What problem are we solving?” instead of “What program should we buy?”

- Stronger professional development: The trip becomes the beginning of an implementation cycle, not a one-off experience.

If you’re responsible for workforce development outcomes—digital skills, collaboration, problem-solving—this matters. Those student skills depend on adult systems: schedules, pedagogy, curriculum materials, and how technology is deployed.

What Finland shows about whole-child development (and why it’s not “soft”)

The most useful takeaway from Finland isn’t a single classroom trick. It’s a stance: whole-child development is treated as an operating system, not an add-on.

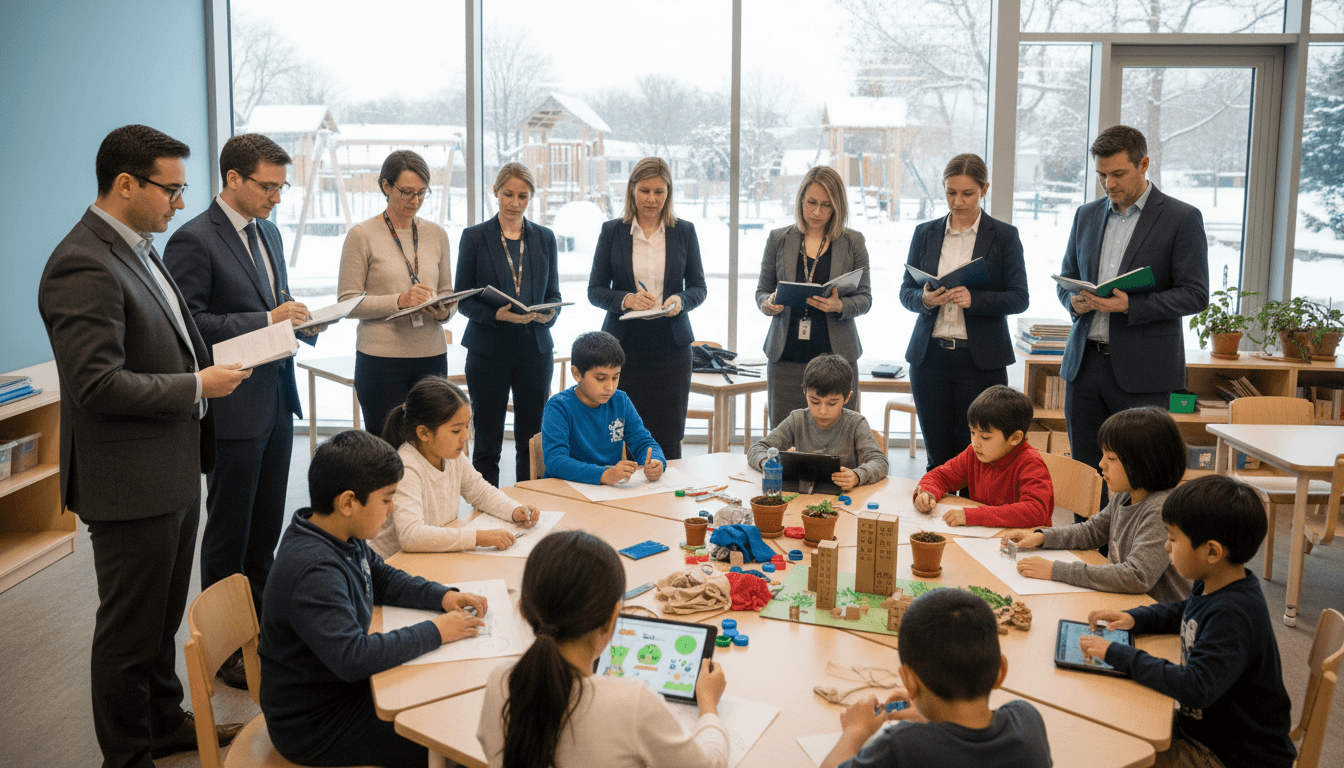

U.S. leaders visiting Helsinki in a whole-child development cohort saw structures that make social, emotional, and physical wellbeing part of the school day—not a reward for good behavior or a separate initiative managed by one department.

Outdoor play isn’t a break from learning—it's part of the learning model

One observation that sticks: some Finnish students spend two hours outside before beginning problem- and project-based learning, then return outside again midday before finishing classroom work.

That routine does three things that connect directly to workforce skills:

- Builds self-regulation: Students practice managing energy, focus, and emotions—skills that predict persistence.

- Improves collaboration: Outdoor play forces negotiation and teamwork without constant adult mediation.

- Supports cognitive performance: Movement and fresh air aren’t “extras” when you’re asking kids to do complex thinking later.

In Connecticut, a district leader brought this insight home by running professional development for elementary educators on play-based learning and how to integrate it with academics. That’s the right move. The U.S. mistake is treating play as something you do after the “real” learning. Finland treats it as part of the pathway to deeper learning.

A whole-child approach is also an equity strategy

Districts serving diverse communities—multilingual learners, varied socioeconomic backgrounds, students needing additional support—can’t rely on a one-size-fits-all classroom. A whole-child approach gives educators a framework to respond to real needs without lowering expectations.

If your district is working on career pathways, you can translate “whole-child” into operational language:

- Attendance and belonging are inputs to career readiness.

- Mental health supports are infrastructure for academic growth.

- Physical movement and play are conditions for sustained attention and problem-solving.

That framing helps leaders fund whole-child systems even when budgets are tight.

The “Fox Book” lesson: innovation travels best when it becomes local

The most effective ideas don’t arrive as imported programs. They arrive as patterns you can remake.

A district leader visiting Helsinki learned about the Fox Book, a citywide environmental curriculum for elementary students focused on sustainability and problem-solving. The characters are local animals children recognize, and the stories connect to the real environment kids live in.

Back in rural Pennsylvania, that leader created a local version: “The Goat Book” (Growing Our Awareness Together). Same instructional pattern—local characters, sustainability themes, standards alignment—but tailored to the community’s identity (including a goat on campus). AI tools supported character creation and narrative development, while grade-level teams ensured instructional coherence.

This example matters for two reasons:

1) It’s a realistic model for AI in education

AI here isn’t grading essays or replacing teaching. It’s doing what it should do in schools: helping educators build materials faster so they can spend more time on instruction.

If you want an “AI policy” that actually works, start with use cases like this:

- Drafting differentiated reading passages

- Generating example problems aligned to standards

- Creating visuals and story elements for locally relevant curriculum

- Translating family communications (with human review)

2) It strengthens skills-based learning early

Sustainability curricula can easily become posters and slogans. Done well, it becomes an early pathway into workforce-relevant competencies:

- Systems thinking (how ecosystems and communities interact)

- Problem definition (what are we actually trying to change?)

- Evidence-based reasoning (what data would we need?)

- Civic collaboration (who has to be involved?)

That’s workforce development, starting in elementary school, without forcing career talk onto six-year-olds.

Uruguay’s digital learning model: equity + teacher training + governance

Uruguay offers a powerful counterpoint to the U.S. pattern of uneven access: pockets of excellent technology use surrounded by schools that are under-connected, under-supported, or overwhelmed.

On a study tour in Montevideo, education leaders observed how Uruguay built national efforts toward equitable access to digital learning in and out of school, paired with teacher training that helps educators use technology in both rural and urban contexts.

The core insight: devices and platforms don’t create digital transformation. Systems do.

What U.S. districts can borrow without copying Uruguay

You don’t need a national model to act like one locally. Here’s what translates at the district level:

- A clear instructional “north star” for technology-enabled learning (what should learning look like with tech?)

- Training that’s tied to classroom routines, not tool features

- Support structures for rural connectivity and after-hours access, so learning isn’t dependent on zip code

- A governance plan: privacy, procurement, interoperability, and long-term total cost of ownership

If your district is focused on workforce development, this is the crux: students can’t build digital skills on sporadic access and inconsistent expectations. Equity in digital learning is a prerequisite for equitable career options.

How to turn an international tour into measurable improvement

Most trips fail at home for a simple reason: leaders return inspired, then re-enter a calendar designed to crush inspiration.

The fix is to treat global learning as a 12–18 month implementation cycle, not a travel event. The strongest cohorts build time for sensemaking, planning, piloting, measurement, and peer feedback.

A simple 5-step “Tour-to-Transfer” playbook

-

Name the problem before you travel. Pick one or two district priorities (chronic absenteeism, literacy growth, AI-ready curriculum design, multilingual learner supports). If you can’t say what success looks like, you can’t recognize it abroad.

-

Collect artifacts, not just impressions. Bring back schedules, sample lesson structures, staff role descriptions, student work examples, and assessment routines.

-

Translate practices into constraints. Ask: What’s the smallest version of this we can run inside our staffing model, bell schedule, and union agreements?

-

Pilot in 90 days. A pilot should be short, specific, and measurable. Examples:

- Add structured outdoor learning blocks for grades K–2 at two schools.

- Build one local sustainability unit using AI-assisted materials with human review.

- Run a teacher tech routine series (3 sessions) focused on one instructional shift.

-

Measure what adults do, not just what students feel. Student surveys are helpful, but implementation lives in adult behavior. Track:

- Minutes of outdoor learning scheduled and actually used

- Number of standards-aligned units produced and taught

- Teacher adoption of agreed routines (e.g., feedback cycles, project checkpoints)

- Student access metrics (logins, device availability, after-hours access)

That measurement approach keeps the work grounded—and protects it when leadership changes.

People also ask: Are international study tours worth it?

Yes—when they’re designed as professional development with deliverables.

A tour is worth funding when it produces at least one of the following within a year:

- A new or improved instructional model (documented routines, schedule, and training)

- A scalable curriculum asset (units, assessments, performance tasks)

- A districtwide policy improvement (AI use guidelines, device refresh plan, procurement standards)

- Evidence of impact (improved attendance, better engagement, stronger course completion, improved access)

If the only outcome is “we were inspired,” you paid for a story. Districts need a system.

A practical next step for leaders building skills and career readiness

Global study tours are one of the most underused tools in leadership development. They create a rare condition: time away from local politics, paired with real examples and peers who will challenge your assumptions. For districts trying to modernize learning—whole-child supports, AI-aware curriculum development, equitable digital learning—this is exactly the kind of professional development that strengthens the workforce behind the workforce.

The real question isn’t whether other countries do school “better.” The real question is: Which practices, seen in context, will help your district build durable skills—literacy, collaboration, problem-solving, digital fluency—without blowing the budget?

If you could take one practice from another system and implement it in the next 90 days, what would you choose—and what would you stop doing to make room for it?