58% of child care providers reported hunger in 2025. That’s a workforce development problem that hits training completion, retention, and local talent pipelines.

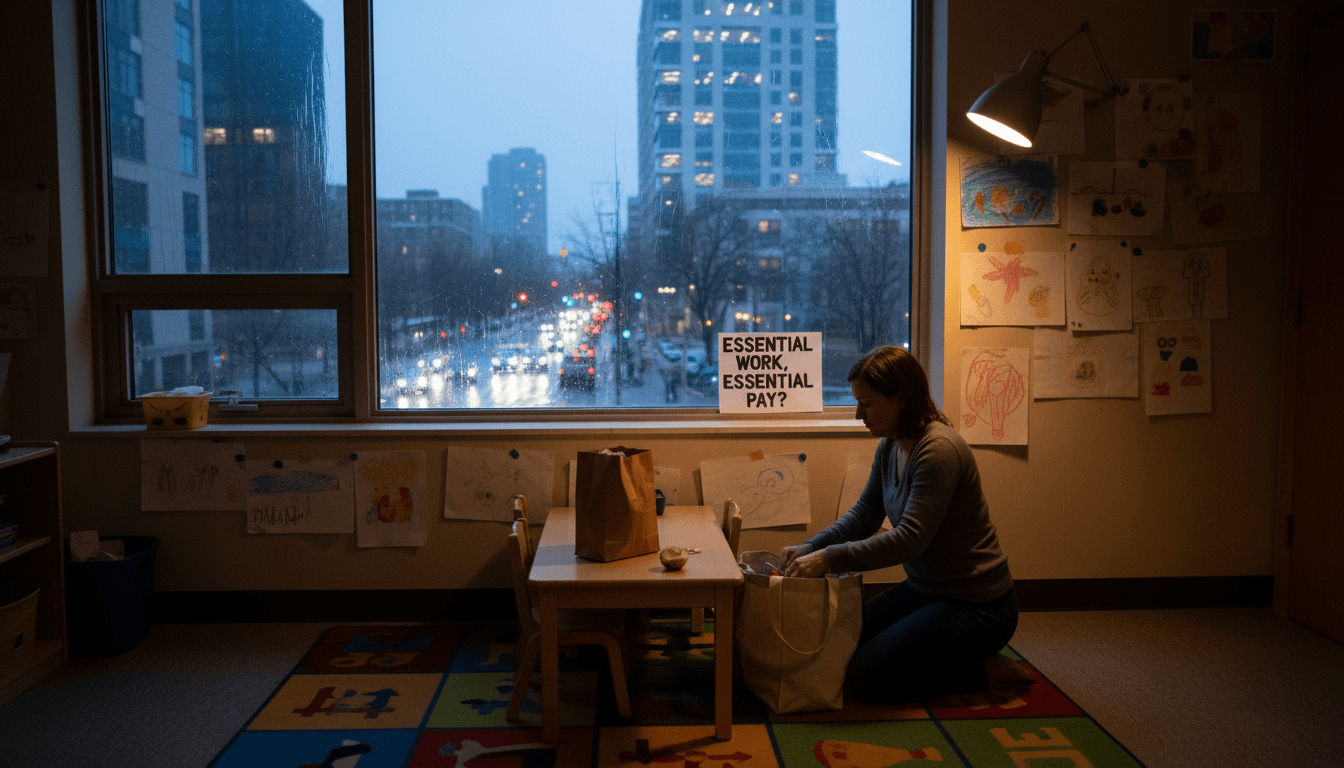

Child Care Worker Hunger Is a Workforce Crisis

58% of child care providers surveyed reported experiencing hunger in June 2025. That’s not a “sad story” for the education section—it’s an alarm bell for anyone working on skills gaps, talent pipelines, and workforce readiness.

When the people who care for children can’t reliably afford food, the entire system wobbles: programs close, turnover climbs, and parents lose the stable care they need to keep a job, finish a credential, or show up for training. The reality is blunt: you can’t build a strong workforce development pipeline on top of an unstable child care workforce.

December adds another layer. This is the season when many families and providers feel the squeeze most—higher heating bills, holiday costs, and fewer “extra hours” to make up lost income. If we want 2026 to be a year of stronger participation in adult education, apprenticeships, and upskilling programs, child care workforce well-being has to move from “nice to have” to “core infrastructure.”

The report’s headline hides the bigger story

The key point: child care provider hunger is a leading indicator of broader labor market fragility. A new survey from Stanford’s RAPID Survey Project found that 58% of child care providers experienced hunger in June 2025, one of the highest levels observed since the project began tracking in 2021.

This isn’t only about one rough month. From June 2021 through May 2025, an average of 44% of surveyed providers reported hunger—already a staggering baseline. The jump to 58% signals that the combination of high grocery prices, low wages, and fraying public supports is pushing essential workers into crisis.

The RAPID Project categorized respondents as “hungry” if they experienced at least two of these scenarios:

- Couldn’t afford to replace spoiled food

- Couldn’t afford balanced meals

- Cut meal sizes or skipped meals due to lack of money

- Ate less than they felt they should

- Were hungry but didn’t eat because food money ran out

That list matters because it captures the everyday trade-offs behind the statistic: health insurance vs. groceries, rent vs. dinner, “keep the center open” vs. personal survival.

Why this is a workforce development issue (not just a social issue)

The direct connection: unstable child care reduces labor force participation and training completion. Workforce development leaders often focus on curriculum, employer demand, and wraparound supports for learners. Child care is frequently treated as one wraparound among many.

That framing understates it. Child care is labor market infrastructure. When care is unstable, it ripples outward:

- Parents miss shifts or drop out of training when a provider closes or staffing is short.

- Adult learners stop attending evening classes if their provider can’t cover extended hours.

- Apprentices struggle to meet hour requirements if their care arrangement falls apart.

I’ve found that workforce programs that treat child care as “a referral list” get predictable results: attendance drops, persistence suffers, and staff spend months troubleshooting crises that were baked in from day one.

There’s also a second-order effect: when providers are hungry, the workforce pipeline for early childhood education shrinks. People leave. Fewer new educators enter. Programs cap enrollment. Families lose slots. Local employers lose workers.

This is how a child care crisis becomes a regional skills crisis.

The affordability paradox is crushing the system

Here’s the contradiction: families pay more, workers earn less, and everyone loses. Child care costs have risen so much that in most states parents pay more each month for child care than housing costs like rent or a mortgage.

At the same time, average wages remain extremely low:

- Average pay for a child care worker: under $12.25/hour

- Child care workers with a college degree: about $14.70/hour

That wage structure doesn’t just create hardship; it creates churn. And churn is expensive:

- Providers leave for better-paying jobs in retail, warehouses, or health care support roles.

- Centers spend time and money recruiting, onboarding, and covering classrooms.

- Quality drops when experienced staff exit.

Workforce development programs talk a lot about “career pathways.” Child care has one of the weakest pathways in practice, even though it’s foundational to every other pathway we want people to complete.

Hunger isn’t evenly distributed—and scheduling is a big reason

The key driver: irregular hours and unstable schedules increase food insecurity risk. The report highlights that food insecurity spans provider types, but rates vary:

- Center-based directors reported the lowest food insecurity

- Home-based providers were higher

- Center-based teachers and family/friend/neighbor caregivers were highest

One reason is predictable: control over schedule and income stability. Hourly workers in child care often face volatile weekly hours. If attendance dips, staff can be sent home early. That hits paychecks immediately.

This is exactly the pattern that undermines workforce readiness across industries: instability makes planning impossible. You can’t budget, you can’t schedule a second job reliably, and you can’t commit to classes if your work hours shift with little notice.

The SNAP “work requirement” problem hits child care workers hard

The practical issue: the system demands stable hours to qualify for support—while child care jobs often don’t provide stable hours. SNAP requires many recipients to work at least 80 hours per month. That sounds straightforward until you’re in a job where you’re regularly sent home early or where weekly hours fluctuate.

Providers who have children of their own face a double bind:

- They need child care to work in child care.

- Their schedules may not meet eligibility requirements consistently.

This is how we end up with a workforce that is simultaneously essential and economically precarious.

What hunger does to the education and training pipeline

The bottom line: provider hunger increases turnover and reduces supply—both weaken workforce development outcomes. Hunger is not an abstract hardship; it changes how organizations function.

1) More closures and fewer available child care slots

When providers can’t meet basic needs, they burn out faster and exit the field. Closures reduce local child care supply, which raises prices further. That makes it harder for parents—especially adult learners—to stay employed or enrolled.

2) Reduced participation in adult education and skills training

Workforce programs often measure success by enrollment and completion. But child care instability hits the key “middle metrics” that determine whether people finish:

- attendance consistency

- on-time arrival

- ability to accept clinical hours or work-based learning shifts

- persistence through setbacks

If we’re serious about increasing completion rates in vocational training and adult education, child care stability needs to be treated as a retention strategy.

3) A thinner future educator pipeline

This is where the education and workforce story merges. Early childhood education is often a first rung on the education career ladder. But if entry-level roles don’t meet basic needs, people won’t stay long enough to become lead teachers, directors, or specialists.

That shrinks the talent pool for early learning—and ultimately affects K–12 readiness too.

Practical moves that actually help (for employers, programs, and policymakers)

The most effective approach is a “basic needs + scheduling + compensation” package, not one-off perks. Food pantries and holiday gift cards help in the moment, but they don’t fix the underlying math.

For workforce development and training providers

Answer first: you can improve completion rates by building child care stability into program design. Start with what you control.

-

Budget for child care supports like you budget for instruction

- Offer stipends that cover real local costs, not symbolic amounts.

- Make supports predictable month-to-month.

-

Schedule training around the care reality

- Offer multiple cohorts (morning/evening/weekend).

- Reduce “mandatory last-minute” schedule changes.

-

Use a simple screening question at intake

- “Do you have reliable child care for the full length of this program?”

- If the answer is “mostly,” treat it as “no” and plan supports.

-

Partner with child care providers as workforce partners

- Not just as vendors, but as co-designers of schedules and supports.

For employers trying to hire and retain workers

Answer first: if you don’t help stabilize child care, you’ll keep paying for absenteeism and turnover. The cheapest option on paper is often the most expensive in practice.

- Offer dependent care benefits or direct child care subsidies.

- Pilot predictable scheduling (posting schedules earlier, limiting last-minute changes).

- Create shift options aligned to local child care hours.

- Consider back-up care support for short-notice disruptions.

Employers don’t need to “solve child care” alone. But pretending it’s outside the business is a mistake—because it shows up in operational metrics every day.

For policymakers and funders

Answer first: raising child care wages and stabilizing public supports is workforce development policy. If we keep treating it as a side issue, we’ll keep getting the same outcomes.

- Fund compensation floors tied to cost of living.

- Support contracts or grants that stabilize provider revenue, so attendance dips don’t immediately cut staff pay.

- Protect access to nutrition supports for low-wage workers with variable schedules.

- Invest in career ladders (paid credentials, apprenticeships for early educators, and paid planning time).

A strong skills strategy doesn’t start at age 18. It starts when families can rely on safe, stable early learning—and when the people providing it can afford dinner.

People also ask: what can organizations do right now?

What’s the fastest way to reduce child care workforce churn?

Increase pay predictably and reduce schedule volatility. One-time bonuses are less effective than steady wage improvements and stable hours.

Why does provider hunger affect program quality?

Hungry, stressed workers burn out faster and leave sooner. That increases turnover, disrupts relationships with children, and forces centers to operate understaffed or cap enrollment.

How does this connect to skills gaps and workforce readiness?

When child care is unstable, parents can’t reliably work or train. That reduces labor force participation and lowers completion rates in vocational training and adult education.

Where this fits in the Education, Skills, and Workforce Development series

This series is about what actually determines whether communities can build skills at scale—training access, completion, and job mobility. Child care provider hunger belongs in that conversation because it’s a constraint on the entire system.

If the workforce that enables everyone else to work is going hungry, we’re not dealing with an isolated hardship. We’re dealing with a structural failure—and it will show up in every headline about labor shortages.

The next step is practical: if you run a workforce program, fund one, or hire at scale, audit your plans for child care stability. Where are the hidden assumptions? Where does your strategy depend on a fragile child care system “just working”? Fix those weak points now, before 2026’s policy and economic shifts make them harder to solve.

What would change in your organization’s retention numbers if child care stability was treated as core infrastructure, not a referral link?