Nigeria’s AI creator economy runs on data centers. Learn the global pitfalls—heat, power, water, jobs—and how Nigeria can build smarter, cheaper compute.

Nigeria’s AI Data Centers: Avoiding the Global Fallout

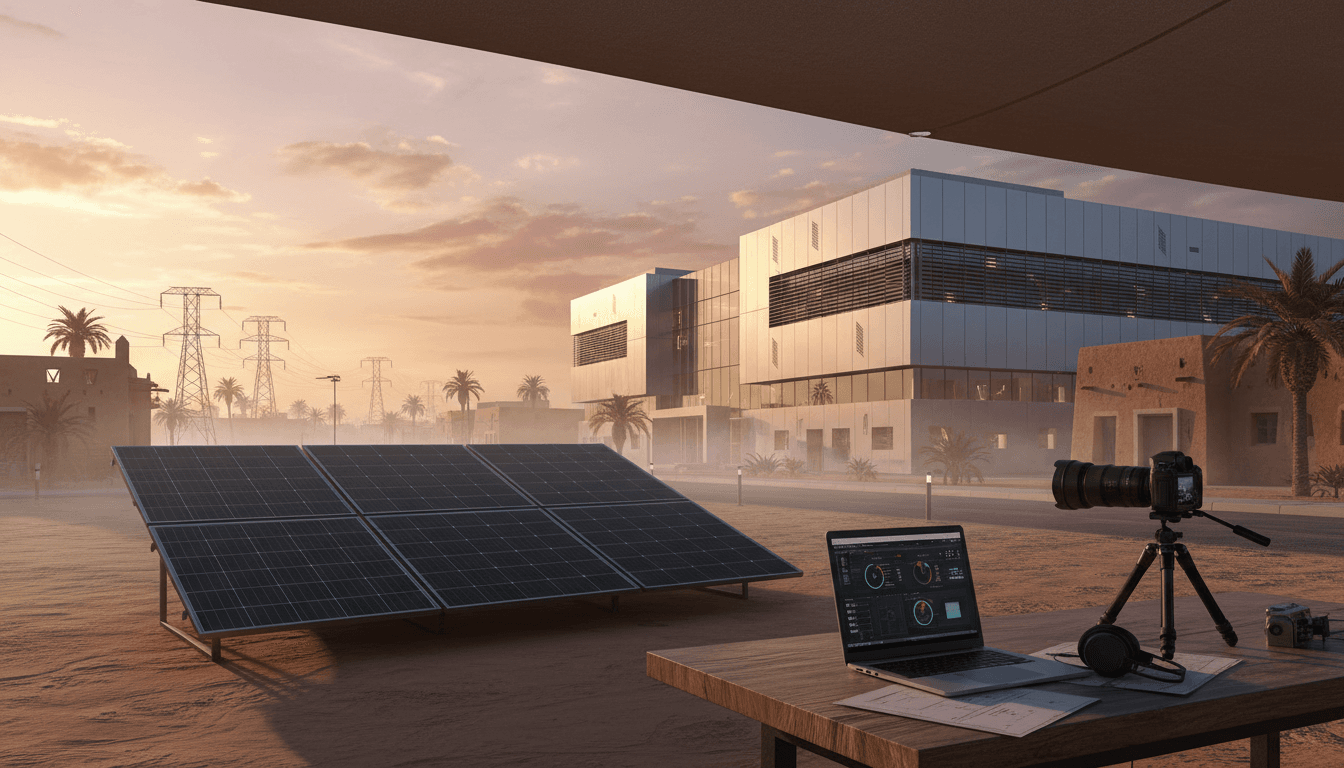

Nigeria’s creator economy is scaling on a hidden backbone: compute. Every AI-generated thumbnail, caption rewrite, voiceover, video render, recommendation feed, and analytics dashboard ultimately runs on servers somewhere. Globally, governments rushed to welcome data centers for jobs, investment, and “digital sovereignty.” Now many are discovering the hard part: heat, power, water, and public trust.

A recent global investigation highlighted a blunt reality: in 21 countries, every data center sits in regions where average temperatures are too high for efficient operation. In places like Singapore and the UAE, that means higher cooling loads and higher electricity bills. In Mexico, limited grid capacity has pushed major operators to rely on gas generators. In Brazil and Chile, the backlash is less about tech optimism and more about water use, land impact, and overpromised jobs.

This matters for our series, How AI Is Powering Nigeria’s Digital Content & Creator Economy, because Nigeria is right at the point where infrastructure choices start to compound. If we get the data center strategy right, creators get cheaper tools, faster workflows, and more reliable platforms. If we get it wrong, we’ll see higher costs, louder community resistance, and a creator economy that grows on unstable foundations.

The global warning: data centers aren’t “pure digital”

Data centers are physical industrial facilities, and the world is relearning that lesson the hard way. They consume electricity at scale, need water or alternative cooling, demand stable land and permitting, and place heavy requirements on national grids.

The fallout shows up in three patterns:

1) Heat makes “AI infrastructure” much more expensive

The hot-country problem isn’t abstract. When ambient temperatures are high, cooling systems work harder, efficiency drops, and operators either pay more for power or invest in complex cooling designs. That extra cost eventually lands somewhere—often in higher cloud prices, higher platform costs, or slower expansion.

For Nigeria, where temperature is high across much of the year, the lesson is simple: assume cooling is a first-order cost, not an afterthought. The cheapest data center on paper can become the most expensive one once energy and cooling are priced honestly.

2) Power constraints lead to dirty “workarounds”

Mexico’s example is a wake-up call: when grid capacity can’t support demand, operators don’t just stop building. They self-supply, often with fossil fuel generators. That keeps services running but undercuts climate goals and worsens local air quality.

Nigeria already knows what “self-supply” looks like across the broader economy. If large-scale AI data centers repeat that pattern, we risk building digital infrastructure that’s reliable only because it’s backed by expensive, polluting power.

3) Job promises are frequently inflated

Governments often sell hyperscale data centers as mass job creators. Permit filings and on-the-ground realities show a different story: the biggest facilities can employ only hundreds of full-time workers, commonly in security, cleaning, and facility operations.

That doesn’t mean data centers are “bad.” It means the value proposition should be honest: data centers create more economic value through enabling ecosystems—software, cloud services, startups, AI tooling, platform businesses, and creator monetization—than through direct headcount on-site.

What Nigeria should do differently (and why creators should care)

Nigeria can still become a leader in sustainable AI infrastructure in West Africa. But it won’t happen by copying the hype playbook. It happens by connecting data center policy to the real needs of the digital content economy: uptime, cost, latency, and trust.

Build for the creator economy, not just for “Big Tech optics”

Nigeria’s AI and digital content economy needs proximity compute, especially for workflows that are time-sensitive:

- video editing and rendering for YouTube and Nollywood production pipelines

- real-time livestreaming and commerce

- AI voice and dubbing tools for multilingual audiences

- recommendation systems and audience analytics for creator brands

- storage for media libraries and production assets

When compute is far away, creators pay in three currencies: higher latency, higher cloud bills, and more downtime risk during peak periods.

Here’s the stance I’m convinced Nigeria needs to take: local data centers should be judged by the experience they enable for SMEs and creators, not by ribbon-cutting narratives.

Don’t let “data sovereignty” become a blank cheque

Storing data locally can be a legitimate goal—privacy, compliance, and resilience matter. But if the trade-off is inefficient, water-stressed, diesel-backed facilities, then the country pays twice: financially and environmentally.

A better approach is sober sovereignty:

- local hosting for truly sensitive and regulated datasets

- regional redundancy for resilience

- strong standards on energy reporting, uptime, and incident disclosure

Creators benefit when the ecosystem is stable and trusted. They lose when infrastructure is built quickly but governed weakly.

The real bottleneck: energy and cooling economics

For hot climates, the data center question is mostly an energy question. Cooling is the multiplier.

Nigeria’s advantage isn’t that power is cheap—it often isn’t. The opportunity is that Nigeria can design policy that forces smarter architecture choices early.

What “efficient” looks like in practice

If Nigeria wants energy-efficient data centers that support AI workloads, the conversation has to include concrete design and procurement choices:

- High-efficiency cooling (including modern air management, hot/cold aisle containment, and climate-appropriate cooling systems)

- Waste-heat planning (even if limited, planning beats ignoring)

- On-site or contracted renewables where feasible, structured as long-term supply agreements

- Grid coordination so facilities don’t arrive faster than transmission upgrades

- Measured efficiency targets (operators should publish key performance indicators, not just marketing claims)

A practical policy stance: if a facility can’t report its energy and water use transparently, it shouldn’t receive premium incentives.

Why creators feel energy costs indirectly

Most Nigerian creators aren’t paying a data center electricity bill. They’re paying through:

- higher cloud subscription fees

- increased ad platform costs (passed on through CPM volatility)

- unstable upload/processing times

- more frequent service interruptions during local grid stress

As AI tools become standard—auto-captioning, generative design, smart editing—compute cost becomes a “creator tax.” Keeping that tax low is infrastructure strategy, not creator advice.

Policy lessons Nigeria can apply right now

The global backlash isn’t just environmental activism. It’s a trust problem: communities feel impacts, while benefits feel distant or exaggerated. Nigeria can avoid that by tightening the policy playbook.

1) Tie incentives to measurable outcomes

Tax breaks and fast permits should come with clear, enforceable requirements:

- energy efficiency benchmarks

- water sourcing plans (including drought contingencies)

- grid interconnection commitments and timelines

- local procurement targets for non-specialized services

- public reporting cadence (quarterly is realistic)

This is how you prevent a race to the bottom where the loudest investor gets the biggest concession.

2) Plan for water transparency before protests force it

Global pushback is increasingly about water—especially where communities are water-stressed. Nigeria should treat water planning as a headline item:

- publish expected annual water consumption

- prioritize cooling methods that reduce freshwater dependence

- require recycling/reuse where feasible

- establish community reporting channels for environmental concerns

If you wait until people are angry, every number looks suspicious.

3) Be honest about jobs—and sell the real upside

Data centers don’t have to employ tens of thousands of people to be worthwhile. The economic win is that they enable:

- Nigerian AI startups building creator tools

- local adtech and analytics firms processing data nearer to users

- media and entertainment pipelines that don’t depend on faraway regions

- fintech and commerce platforms with better latency and reliability

The message should be: data centers are not job factories; they’re productivity infrastructure.

A solid data center strategy doesn’t promise “81,000 jobs.” It promises cheaper compute, better uptime, and a wave of businesses built on top.

People also ask: what does this mean for Nigerian creators and marketers?

Should creators care where AI tools are hosted?

Yes. Hosting location affects speed, reliability, and sometimes price. If your workflow depends on rendering, transcription, or bulk content generation, proximity compute can shave hours off turnaround time over a month.

Will Nigeria get cheaper AI tools by building more data centers?

Not automatically. Prices drop when data centers are efficient, competition is real, and power is stable. More capacity built on expensive, generator-heavy power can keep prices stubbornly high.

What can businesses do while infrastructure catches up?

Three practical moves I’ve found helpful:

- Audit your AI spend: separate “nice-to-have” tooling from revenue-linked tooling.

- Design for outages: offline drafts, queued uploads, redundant storage.

- Batch heavy compute: schedule rendering/transcoding in off-peak windows when possible.

These aren’t glamorous, but they protect margins.

A smarter path: build the stack Nigeria’s creator economy needs

Nigeria’s digital content economy is not waiting. Brands are shifting budgets to creators. Video is still eating the internet. AI editing and content automation are becoming normal workflow, not a novelty. The risk is building AI infrastructure with the same short-term logic that has caused global blowback: vague job claims, weak reporting, and power plans that quietly default to fossil workarounds.

A better way is more disciplined: treat data centers like critical national infrastructure and force transparency on energy and water from day one. Make incentives conditional. Coordinate grid upgrades. And keep the “why” grounded in outcomes creators actually feel—faster processing, lower tool costs, and platforms that don’t wobble when demand spikes.

If Nigeria becomes the place where AI data centers are built responsibly in a hot climate—efficient cooling, honest reporting, community buy-in—it won’t just power servers. It’ll power the next wave of Nigerian creators who can produce more, ship faster, and compete globally without paying a hidden infrastructure penalty.

Where do you think Nigeria should draw the line—between attracting investment fast and enforcing the standards that keep AI infrastructure sustainable?