NCAR underpins the data and models that power AI-driven city resilience. Here’s what public sector leaders should do to protect forecasts, warnings, and data integration.

Why NCAR Matters for AI-Ready City Resilience

Emergency managers aren’t panicking because they think weather forecasts will vanish overnight. They’re pushing back because if the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) is dismantled, forecasts and warnings are far less likely to improve—and that improvement curve is what saves lives and money.

That’s the uncomfortable part: the damage from breaking up a climate research center isn’t dramatic on day one. It’s a slow leak in capability. And for cities trying to build AI-supported services—flood prediction, wildfire smoke alerts, heat-health triggers, stormwater optimization—a slow leak in the national research pipeline becomes a local failure mode.

This post is part of the “Mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā un viedajās pilsētās” series, where the focus isn’t AI for AI’s sake. It’s AI that actually improves public services. Here, the message is direct: smart city resilience depends on boring, foundational climate data infrastructure—and NCAR is a major pillar of it.

The real issue: forecasts won’t stop, but progress will

Answer first: Dismantling NCAR wouldn’t end forecasting tomorrow; it would slow the research-to-operations pipeline that steadily improves hazardous weather warnings.

In the RSS article, emergency managers and meteorologists describe NCAR as a core engine of U.S. weather and climate capability. The concern is not whether a city gets a forecast tomorrow. The concern is whether that forecast gets better next year, and better again five years from now.

Here’s why that matters to public sector leaders:

- Emergency management runs on lead time. Extra hours (or even minutes) of warning for flash floods, severe storms, or wildfire shifts translate into evacuations completed, roads closed in time, and fewer rescues.

- Infrastructure planning runs on extremes, not averages. Stormwater systems, culverts, bridges, grid hardening, and land-use rules require credible modeling of rare-but-devastating events.

- AI systems are only as good as the data and models beneath them. If the national research ecosystem degrades, local AI deployments quietly become less reliable.

A line from the article captures the risk cleanly: you’ll still have a forecast tomorrow—the problem is it won’t get better. Cities should read that as: your risk management won’t get better either.

Climate research is the upstream supply chain for smart city AI

Answer first: NCAR-type research isn’t “nice to have.” It’s upstream infrastructure for AI-driven environmental monitoring, early warning systems, and data-driven policy.

Most city AI projects in climate and resilience share the same skeleton:

- Observation (radar, satellites, sensors, IoT, gauges)

- Modeling (numerical weather prediction, hydrology, fire spread, air quality)

- Decision logic (thresholds, runbooks, alerting, resource allocation)

- Communication (public warnings, targeted outreach, multilingual messaging)

NCAR contributes heavily to step 2—and increasingly to step 4 via social science research that improves how warnings are communicated and acted upon.

Here’s the part that’s often missed in “smart city” discussions: cities rarely build foundational models from scratch. They build services on top of national science, operational agencies, and shared toolchains.

So when a national research center is destabilized, cities don’t just lose abstract “climate science.” They lose:

- model improvements that make flood forecasts more accurate,

- research that helps radar interpret hail or tornado signatures,

- methods that reduce false alarms (a major driver of public distrust),

- better ensemble forecasting that quantifies uncertainty—critical for AI risk scoring.

If your municipality is investing in AI for public safety, climate adaptation, or infrastructure management, you’re already downstream of institutions like NCAR.

A practical way to think about it

I’ve found it helps to frame NCAR as a public sector equivalent of a shared platform:

- Cities don’t individually fund the invention of GPS.

- They build emergency routing, snowplow tracking, and transit apps on top of it.

Weather and climate research works the same way. The shared platform is the science, models, and datasets. AI is the interface layer that turns them into actionable municipal services.

Public safety impact: the warning chain is only as strong as its research base

Answer first: Weakening NCAR increases the probability of slower warning improvements, worse calibration, and less effective communication, which directly affects local public safety outcomes.

The article quotes meteorologists and emergency managers who rely on advances that flow into the National Weather Service and other operational partners. This is the “research-to-operations” pipeline that cities depend on—often without realizing it.

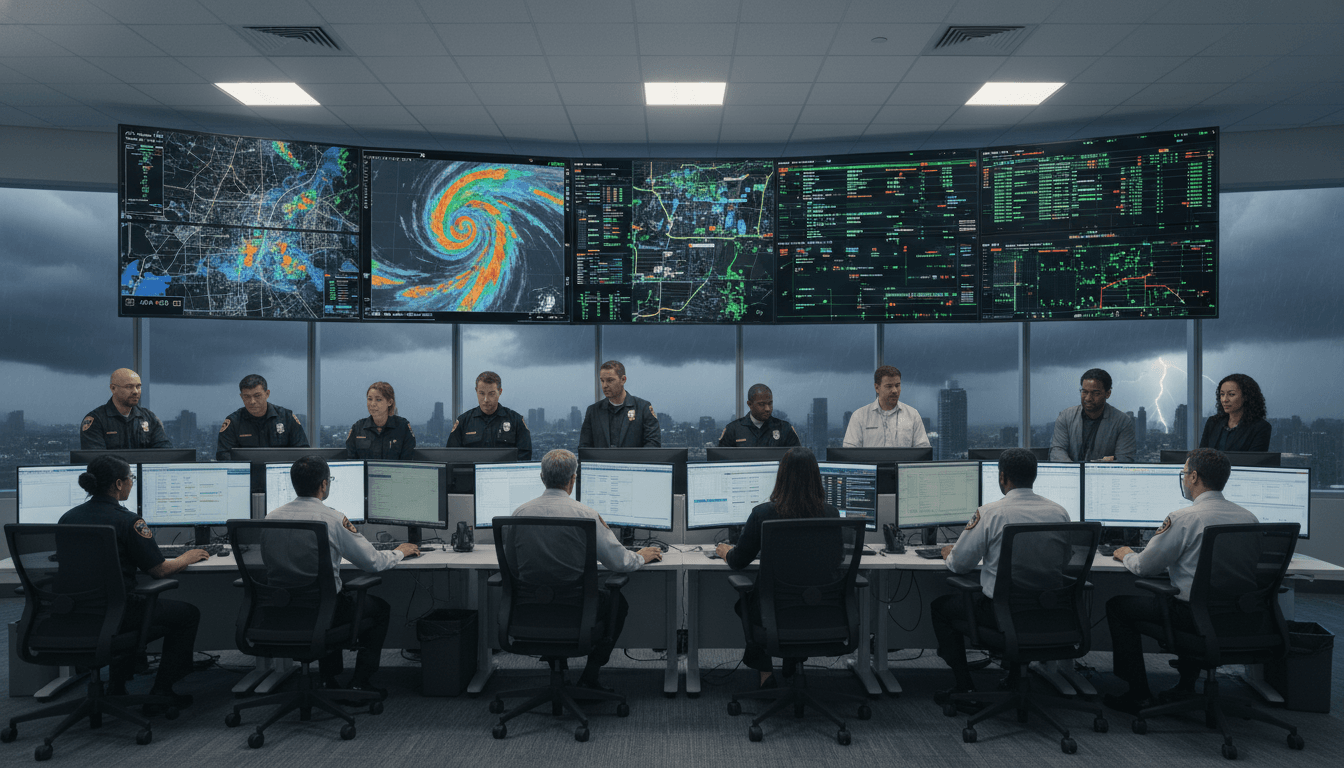

For smart cities, the warning chain typically looks like:

- national guidance (models and outlooks)

- regional forecasting offices

- local emergency operations

- city alerting systems (SMS, apps, sirens, dynamic signs)

- community response

AI can strengthen parts of that chain—especially triage and communication—but AI also introduces new failure modes:

- Automation bias: when staff over-trust model outputs

- Alert fatigue: when systems trigger too often

- Equity gaps: when alerts don’t reach the right people, in the right language, on the right channel

NCAR’s contribution to social science research matters here. Better messaging research reduces the “last mile” failure: people receiving warnings but not taking protective action.

A city doesn’t fail resilience because it lacked an algorithm. It fails because the algorithm didn’t translate into human action.

Data integration is the hidden work that makes AI useful

Answer first: The strongest city AI programs succeed because they treat climate and weather information as an integrated data product, not a collection of dashboards.

The campaign theme—AI in public sector and smart cities—often gets pulled toward shiny pilots. The less glamorous reality is that integration is where capability is built.

If national climate research capacity is disrupted, cities should respond by getting stricter (not looser) about integration discipline:

What “AI-ready” climate data integration looks like in a municipality

- One event timeline: unify 911 calls, road closures, rainfall totals, river stage, power outages, and hospital surge into a shared operational view.

- A common location layer: consistent addresses, parcels, road segments, critical facilities, and evacuation zones.

- Model provenance and versioning: track which forecast model/version informed which decision (especially for after-action reviews).

- Clear thresholds tied to actions: not “high risk” but “deploy barricades,” “open warming center,” “pre-stage pumps.”

AI becomes credible when it’s auditable. And auditability requires integrated, governed data.

Two city use cases where integration beats fancy modeling

- Flash flood operations: Even a modest model paired with well-integrated sensor data and road network status can outperform a complex model that lives in a silo.

- Extreme heat response: Linking forecast heat indices to health calls, shelter capacity, and targeted outreach lists is often more impactful than building a novel prediction model.

If NCAR’s pipeline slows, cities should compensate by tightening their local data loop—the feedback that turns forecasts into operational learning.

What city leaders can do now (even if they can’t control federal decisions)

Answer first: Cities can reduce exposure by treating weather and climate capability as a continuity-of-operations dependency and investing in resilient data partnerships.

Here are concrete steps that fit a public sector reality—budgets, procurement rules, and staffing constraints included.

1) Map your “forecast dependencies” like any other critical supplier

Create a simple dependency map:

- Which departments use weather/climate inputs? (public works, transit, utilities, public safety, parks)

- Which systems ingest them? (alerting, SCADA, asset management, GIS)

- What breaks if inputs degrade? (lead times, staffing plans, route optimization)

This is basic risk management, but most cities haven’t done it for environmental intelligence.

2) Build a minimum viable “resilience data product”

Pick one hazard with real seasonal relevance—December is a good time to plan for winter storms and flooding—and design a data product that operational staff actually use.

A minimum viable version includes:

- a shared dashboard for situational awareness,

- an alerting rule set,

- a post-event review template that captures what the data got right/wrong.

3) Make AI serve decisions, not the other way around

If your AI output doesn’t change a decision, it’s decoration.

Define:

- the decision (close a road, pre-stage crews, open shelters),

- the decision owner,

- the time window,

- the acceptable error rate.

Then build your model or automation.

4) Invest in communication design as much as prediction

The article calls out the importance of research into services and communication. Cities can act locally:

- Write alert templates in plain language.

- Pre-approve translations.

- Test messages with community organizations.

- Use multiple channels (SMS + radio + dynamic signs + social).

Prediction without communication is just internal reporting.

5) Formalize partnerships and data sharing

When national structures feel uncertain, local-to-regional partnerships become more valuable:

- regional emergency management coalitions

- utility coordination groups

- university research partners

- mutual aid agreements that include data-sharing terms

This isn’t glamorous, but it’s how resilience scales.

The stance cities should take: protect the science, modernize the delivery

Answer first: Public sector AI needs strong national research institutions; cities should push for continuity of climate research while modernizing how insights reach local operations.

The public debate around NCAR is being framed politically. Cities should reframe it operationally: this is about national data infrastructure that underwrites local public safety.

At the same time, local governments can be honest about a second truth: the path from research to a dispatcher’s screen or a public works supervisor’s shift plan is still too slow in many places. That’s where smart city programs can help—through integration, automation, and governance.

The strongest outcome is not “science vs. AI.” It’s science that remains well-funded and stable, plus AI and integrated data systems that convert that science into faster, clearer municipal action.

If you’re working in a municipality, a ministry, or a public agency building AI-supported resilience: what would your city’s flood, heat, or wildfire program look like if forecast skill stopped improving for the next five years? That’s the planning stress test this moment is forcing—whether we like it or not.