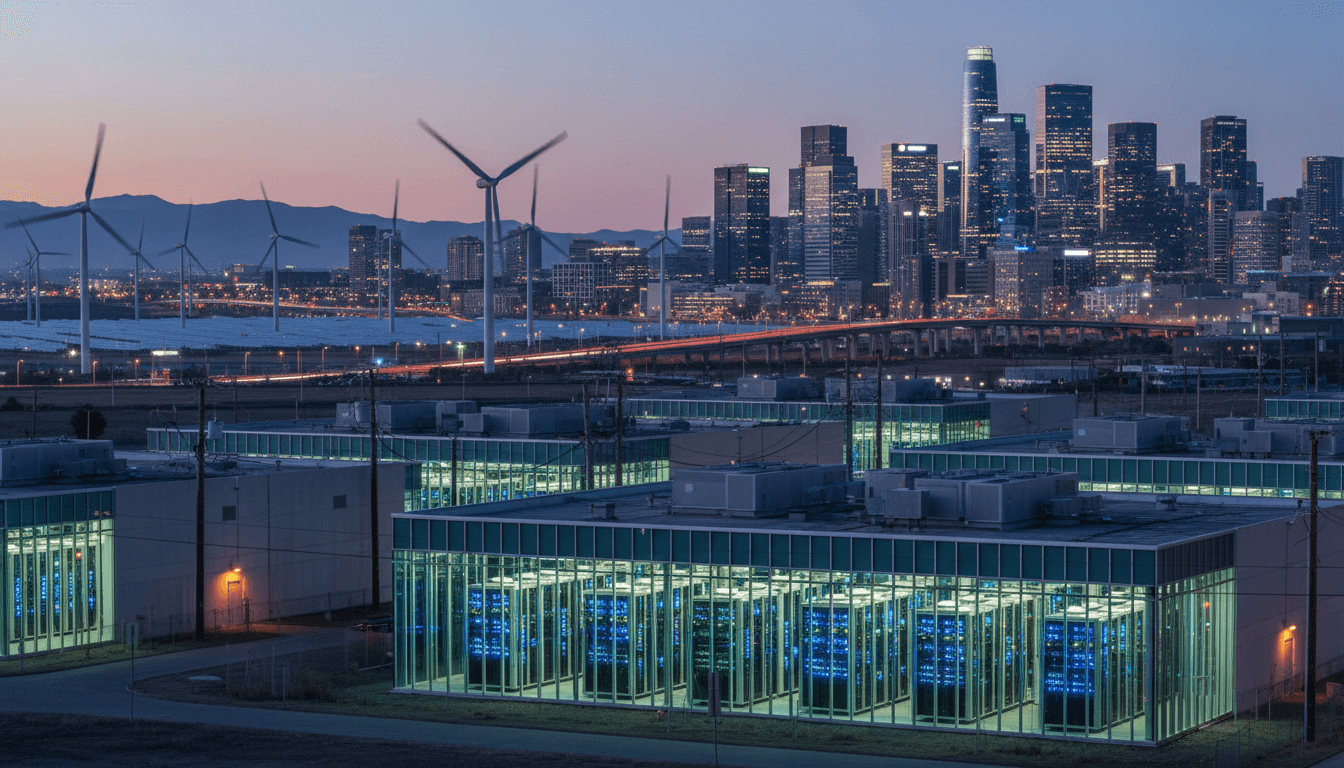

Fair-share energy policy is becoming an AI policy. Here’s how data centers, grids, and public sector AI must align to keep smart cities affordable.

Data Centers Must Pay Fair Share for Smart Cities

Virginia just got a very public reminder that AI infrastructure isn’t “virtual.” It’s physical, power-hungry, and tied to real household bills.

In mid-December, Virginia’s incoming leadership signaled a policy shift: data centers should “pay their fair share” for the energy system they rely on, including by bringing more of their own power to the table and getting clean generation connected faster. That’s not a niche utility debate. It’s a core question for anyone working on mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā, smart city platforms, and digital public services.

Because here’s the uncomfortable truth: you can’t scale AI in government, transport, safety, or city operations if the grid buckles or citizens see energy bills spike. If AI is going to be a public good, the infrastructure under it can’t quietly become a public subsidy.

Why “fair share” is really about AI governance

Fair share policies are AI policies. Data centers run the compute behind everything from generative AI to real-time video analytics, digital identity services, and citywide sensor platforms. When those facilities drive up electricity demand, the downstream impact shows up in:

- Grid capacity constraints

- More expensive wholesale power procurement

- Faster buildout of transmission and distribution

- Public backlash when bills rise

Virginia’s debate highlights the political risk that many regions are underestimating: AI adoption in the public sector will be judged not just on service quality, but on cost-of-living impacts. If residents feel they’re paying more so hyperscale facilities can expand, trust erodes—fast.

For smart cities, this matters because public agencies increasingly depend on external cloud and colocation providers to deliver:

- Intelligent traffic management

- Predictive maintenance for infrastructure

- Digital permitting and e-governance automation

- Emergency response coordination and situational awareness

The compute may live in a data center, but the accountability lands on elected officials.

What Virginia’s energy numbers are really telling us

Energy affordability is becoming the frontline issue. A recent analysis discussed by Virginia leaders projected that a bundle of reforms—data centers supplying more of their own energy, faster clean energy interconnections, lower utility profit margins, and faster electrification—could reduce bills for a typical household by:

- $142 in 2026

- Up to $712 in 2030

At the same time, Virginia regulators approved a utility rate increase expected to raise the typical residential bill by about $11.24 per month in 2026 (around 7.5%).

These figures matter for two reasons:

- They quantify the politics. When policymakers can point to household savings (or rising costs), the debate stops being abstract.

- They expose the system tension. Data center load growth can force utilities to buy more capacity in regional markets during periods of price spikes.

If you’re building AI-enabled city services, treat these signals as early warnings: energy cost and grid capacity will become procurement criteria, not background assumptions.

The hidden subsidy problem

One of the thorniest points in the Virginia discussion is that it’s easier to design tariffs for local wires (distribution upgrades) than it is to assign responsibility for wholesale market impacts like:

- Capacity price spikes

- Regional transmission costs

- System-wide energy price increases

Even when regulators create new “large load” rate classes, a lot of cost pressure can still land on everyone else. The outcome is predictable: residents and small businesses feel squeezed, and AI infrastructure becomes a political target.

My take: if a region wants to be an AI hub, it needs a cost-allocation story that the public can repeat in one sentence and feel is fair.

What “self-supply” can mean (and what it shouldn’t)

Self-supply is a policy shorthand, not a single solution. In practice, governments and regulators can push data centers toward several models:

1) On-site or dedicated clean generation

The strongest version is requiring (or strongly incentivizing) data centers to fund new clean generation—solar, wind, storage, geothermal where feasible—tied directly to their load growth.

Why it helps: it reduces the chance that new load simply raids the existing grid capacity.

What to watch: it must be additional capacity, not paper reshuffling.

2) Flexible load and demand response

A large portion of “fair share” can come from operational behavior, not only generation.

Data centers can provide grid services by:

- Reducing load during peak hours

- Shifting non-urgent compute workloads

- Coordinating with utility demand response programs

This is especially relevant for AI workloads that don’t always need real-time execution.

3) Microgrids and resilience-ready interconnections

If cities are serious about resilience (storms, heat waves, grid congestion), microgrids can keep critical public services running—hospitals, emergency operations centers, traffic signals, water systems.

Data centers can be anchors for local microgrids, but only if interconnection rules and planning processes support it.

The red line: diesel “backstop” dependence

Many data centers still rely heavily on diesel generators for backup. In dense metro areas, that creates local air quality and noise issues.

A “fair share” policy that accelerates AI infrastructure while tolerating widespread diesel runtime is self-defeating for smart city credibility. Clean backup strategies—batteries, fuel cells, cleaner fuels—should be part of the package.

Why smart cities can’t ignore grid planning anymore

Smart city roadmaps often treat energy as a separate domain. That’s a mistake. AI-driven public services increase digital demand, and digital demand increases energy demand—directly or indirectly.

If you’re responsible for AI in the public sector, you’ll increasingly be pulled into conversations about:

- Grid capacity and interconnection queues

- Where data centers cluster and why

- Local zoning and permitting constraints

- Community benefit agreements

- Peak-load risks during heat/cold events

A practical way to connect the dots: “Compute-to-Community” planning

Here’s a planning lens I’ve found useful:

- Map critical AI services (public safety video analytics, traffic control, e-health, digital ID, fraud detection).

- Classify workloads by latency sensitivity:

- Real-time (seconds)

- Near-real-time (minutes)

- Batch (hours)

- Align workload types with energy strategy:

- Real-time systems should be hosted where reliability and redundancy are strongest.

- Batch AI can be shifted geographically or temporally to reduce peak stress.

- Build procurement requirements that force transparency:

- Energy source disclosure

- Emissions reporting

- Demand response participation

- Outage performance metrics

When cities do this, they stop being passive consumers of cloud compute and start acting like infrastructure buyers.

What policymakers should require from data centers powering AI

A fair share framework should be measurable, enforceable, and legible to the public. Based on what’s emerging in Virginia and other markets, strong policies tend to include:

-

Long-term commitment for large loads Contracts and planning horizons need to match the reality that a 25+ MW facility isn’t a “normal customer.”

-

Additional clean energy requirements tied to load growth Not just renewable credits—real capacity added to the system.

-

Grid-support obligations Demand response participation, load flexibility standards, and performance penalties for non-compliance.

-

Transparent cost allocation If households are protected from distribution upgrade costs but still exposed to market-wide impacts, regulators should say so plainly and design mitigation mechanisms.

-

Community benefits that aren’t token gestures Cities hosting heavy infrastructure should see direct value:

- Workforce training pipelines

- Heat reuse pilots (where feasible)

- Local resilience investments

- Funding for municipal digital modernization

Strong stance: if a data center cluster is essential to national AI capacity, then structuring a visible public return isn’t “anti-business.” It’s basic infrastructure governance.

What this means for public sector AI teams (not just utilities)

Even if you don’t run the grid, you will feel its constraints in budgets and service delivery. Public agencies can act now.

Procurement: add energy clauses to AI and cloud contracts

When agencies purchase AI platforms, they can require vendors to disclose and commit to:

- Hosting region energy mix and emissions intensity

- Participation in demand response programs

- Service continuity plans during grid emergencies

- Reporting on compute growth and associated energy impact

This doesn’t need to be ideological. It’s risk management.

Architecture: design for flexibility, not maximum load at peak times

Smart city systems can reduce cost and stress by:

- Scheduling model training and re-training off-peak

- Using edge processing where it reduces backhaul and compute spikes

- Compressing/retaining video intelligently rather than storing everything forever

Governance: connect AI strategy to energy affordability

If your AI program claims it improves quality of life, you should be prepared to explain how it doesn’t raise household energy costs.

A simple internal test:

- If energy prices rose 10% next year, would your AI program still be politically defensible?

If the answer is “maybe not,” the program needs an infrastructure plan.

Where Virginia’s debate points next (and why Europe should watch it)

Virginia is a bellwether because it sits at the intersection of major data center growth and regulated utility structures. The themes translate globally:

- AI growth concentrates in specific regions; the costs and benefits don’t spread evenly.

- Grid queues and capacity are becoming the limiting factor, not software talent.

- Public legitimacy depends on affordability, resilience, and visible fairness.

For Latvia and the broader EU smart city ecosystem, this is a useful preview. As municipalities adopt more AI for e-pārvalde, mobility, and security, the compute behind it will increasingly be questioned:

- Where is it hosted?

- What energy does it consume?

- Who pays when infrastructure expands?

If you can answer those cleanly, you’ll move faster with less public friction.

Next steps: make “fair share” part of your smart city AI plan

If you’re building AI-enabled public services, treat energy policy as a first-order design constraint. The Virginia story shows what happens when compute growth outpaces a shared understanding of costs.

Here’s a practical checklist to start this quarter:

- Inventory which public services depend on data center compute (directly or via cloud vendors).

- Ask vendors for energy and demand response commitments in writing.

- Coordinate with city energy and planning teams before scaling high-compute pilots.

- Publish a short public-facing statement on how your AI roadmap supports affordability and resilience.

Smart cities can thrive with AI, but only if the infrastructure bargain is clear: the benefits are shared, and the costs aren’t quietly socialized.

If data centers are the engines of AI, then fair energy policy is the steering wheel. Who’s holding it in your city?