SF upzoned for 36,000 homes but may build 14,600. See how AI and data tools help cities turn zoning capacity into real housing delivery.

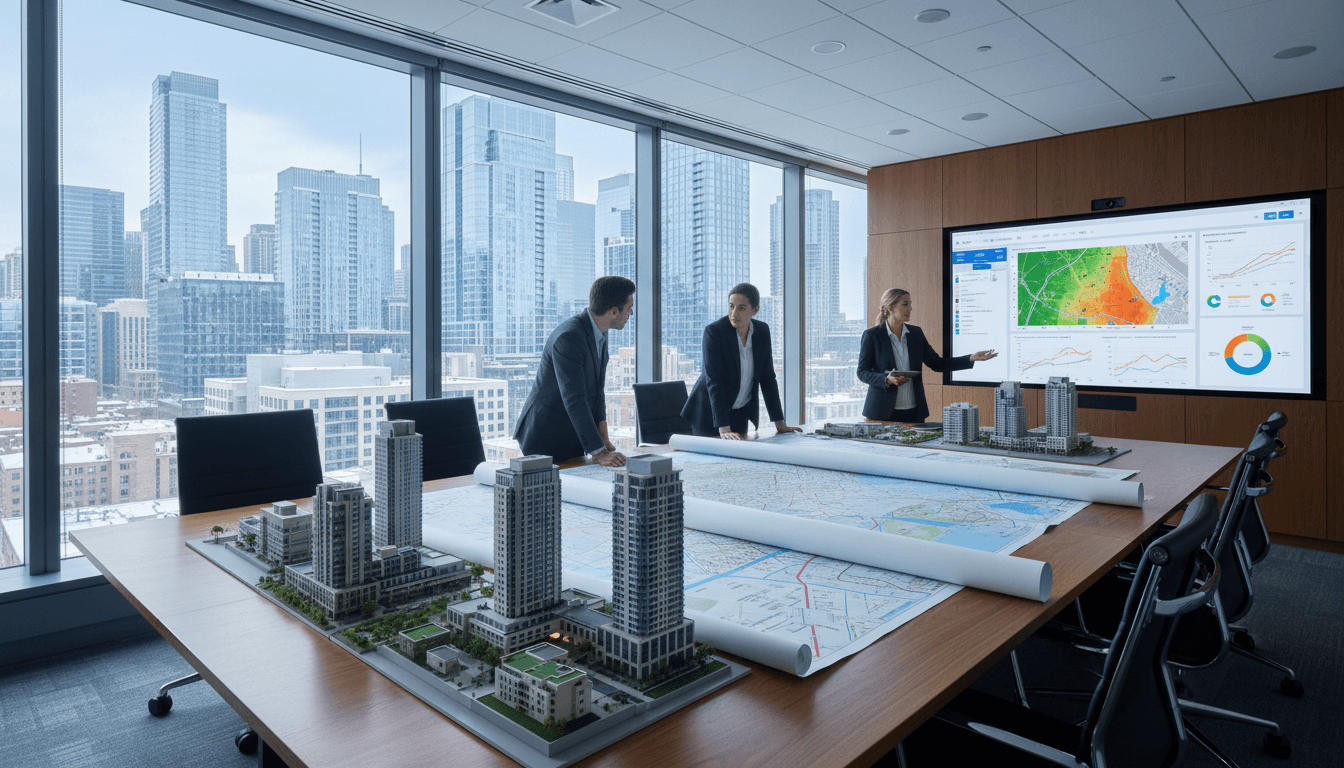

AI in Zoning: Turning Upzoning into Real Housing

San Francisco just approved zoning changes that create capacity for 36,000 homes, but the city’s own economist expects only about 14,600 units to materialize over the next 20 years. That gap—paper capacity vs. real deliveries—is where most housing strategies quietly fail.

And it’s also where the public sector’s AI conversation needs to get more practical. In the “Mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā un viedajās pilsētās” series, we often talk about AI improving services and decision-making. Housing is exactly that kind of problem: it’s messy, political, slow, and full of constraints. Zoning reform matters, but zoning is just permission. The hard part is turning permission into projects that get financed, approved, built, and occupied.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: If a city passes new zoning but can’t predict and manage the bottlenecks that stop projects from happening, it’s doing half the job. AI won’t “fix” housing, but it can help city teams model outcomes, prioritize infrastructure, and avoid self-defeating tradeoffs like displacement risk without replacement.

What San Francisco’s zoning change really tells us

San Francisco’s family zoning plan is a real case study in why smart city planning has to be data-driven. The city needs 82,000 additional units by 2031 to meet state requirements. The new zoning, as described by the city, enables about 36,000 units of capacity—roughly 43% of that target. Yet the forecasted buildout is much lower.

Capacity isn’t production

A blunt way to say it: zoning changes the rulebook, not the market. Real housing production depends on whether projects “pencil out” under actual conditions.

Common reasons capacity doesn’t turn into housing:

- Construction costs outpace rents/sales prices that developers can realistically charge.

- Financing tightens, especially when interest rates stay elevated or lenders become conservative.

- Permitting timelines add uncertainty, which raises risk and cost.

- Infrastructure constraints (sewer, power, transit crowding) limit feasible density.

- Neighborhood friction leads to delays, litigation, or added requirements.

San Francisco’s situation highlights a pattern seen across high-cost cities: upzoning is necessary, but it’s not sufficient.

The political subtext: avoid state takeover, keep local control

The plan was also about governance. The deadline pressure (a state requirement to adopt a compliant rezoning plan by late January 2026) meant the city faced a choice: design its own approach or risk the state stepping in.

This is a core public-sector AI lesson: when timelines compress, decision quality usually drops—unless you have strong decision support systems already in place. Cities shouldn’t wait until mandates arrive to build the modeling capability.

Why the “14,600 units” forecast is the number to pay attention to

The most useful number in the whole story isn’t 36,000. It’s 14,600.

That forecast forces a better question than “How much did we upzone?” The better question is:

What’s stopping the other ~21,400 units from happening—and which levers actually move that number?

Zoning is a supply lever; delivery is a system

Housing delivery is a system with feedback loops:

- Faster approvals reduce carrying costs → more projects qualify → more competition → prices stabilize.

- Underbuilt infrastructure increases project mitigation costs → fewer projects qualify.

- Unmanaged displacement risk triggers backlash → political resistance rises → timelines slow.

So if your city is only measuring “entitlements granted” or “units permitted by-right,” it’s missing the operational reality. The KPI should be expected completions under realistic constraints, updated quarterly.

Economic impact can be positive even when production is modest

San Francisco’s economist also estimated the overall GDP effect could be $560M to $940M. That’s consistent with what we see elsewhere: even incremental housing supply and construction activity ripple through jobs, spending, and mobility.

Still, GDP lift doesn’t automatically mean affordability improves at the scale residents feel. Cities need to treat affordability outcomes like a performance metric, not a press release.

Where AI-driven urban planning actually fits (and where it doesn’t)

AI in the public sector gets overcomplicated fast. For housing and zoning, the most credible use cases are forecasting, prioritization, and workflow intelligence—not “AI decides where people should live.”

1) Scenario modeling: what will actually get built?

Answer first: AI can improve buildout forecasts by integrating many variables at once and updating them frequently.

Traditional planning models often assume static inputs or rely on periodic studies. Modern approaches combine:

- Parcel-level constraints (lot size, slope, historic status)

- Regulatory constraints (height, setbacks, FAR, parking rules)

- Market signals (rents, sales comps, vacancy)

- Cost indices (labor, materials)

- Approval timelines by project type

With machine learning, cities can estimate:

- Probability a parcel redevelops in 3/5/10 years

- Likely unit counts by typology (4-story vs 8-story)

- Sensitivity to policy changes (parking removal, impact fee adjustments)

The goal isn’t perfect prediction. It’s better than guessing—and transparent enough to defend publicly.

2) Permitting intelligence: shorten timelines without lowering standards

Answer first: AI can reduce approval friction by spotting incomplete applications early and routing reviews more efficiently.

This is especially relevant in late 2025: many agencies are juggling staffing constraints, budget scrutiny, and higher citizen expectations for digital services.

Practical applications:

- Automated completeness checks for submissions (missing forms, inconsistent plans)

- Triage routing (which specialists need to review based on project attributes)

- Risk flags (projects likely to trigger code conflicts or neighborhood appeals)

- Document search and summarization for case history (staff time saver)

That’s not flashy. It’s effective.

3) Infrastructure coordination: match density with capacity

Answer first: Upzoning works best when infrastructure investment is sequenced to where housing is most likely to deliver.

If zoning allows two to four additional stories near transit and shopping (as in San Francisco’s plan), then the city needs to check whether:

- Water/sewer capacity supports added load

- Grid capacity can handle electrification trends

- Transit headways and stop capacity can absorb riders

- School and childcare access match family-housing goals

AI-driven planning tools can overlay these systems and identify “high-yield blocks”—areas where small infrastructure upgrades unlock real housing.

4) Equity and displacement: model risk before it becomes backlash

Answer first: Cities can use data models to predict displacement risk and pair upzoning with protections and anti-displacement investments.

Critics of San Francisco’s plan raised displacement concerns and called for stronger tenant protections. This debate shows up everywhere because it’s valid: adding value to land can create pressure on existing tenants.

What works in practice is pairing zoning with targeted measures:

- Preservation funds for naturally affordable buildings

- Acquisition programs for nonprofit housing operators

- Tenant legal support and right-to-counsel policies

- Monitoring systems that flag rent spikes and eviction hotspots

AI can help by forecasting where risk concentrates (based on rent burden, churn, speculative buying, eviction patterns) so policy isn’t reactive.

A “smart city zoning” checklist cities can copy in 2026

Answer first: Treat zoning reform as a product launch: you need analytics, operations, and user protection built in from day one.

Here’s a practical checklist I’d use if I were advising a city team preparing for a rezoning deadline.

1) Define two numbers: capacity and expected delivery

Track both, always:

- Zoning capacity (what’s legally possible)

- Expected delivery (what’s financially and operationally likely)

Set a target to close the gap each year.

2) Instrument the permitting pipeline

If you can’t measure cycle time, you can’t manage it.

- Median days from application to approval

- Rework rates (how often projects come back incomplete)

- Bottleneck stages (design review, utilities, environmental)

3) Publish a quarterly buildout forecast

Not a one-time report. A living model.

- Update assumptions (costs, interest rates, demand)

- Show confidence intervals (best/base/worst case)

- Explain what policy levers change the curve

4) Link zoning to infrastructure funding

Make it explicit:

- Which corridors get upgrades first

- What the upgrade unlocks (expected units)

- What happens if funding slips (units delayed)

5) Pair upzoning with anti-displacement actions

If you don’t plan for it, you’ll end up negotiating it mid-crisis.

- Map risk zones

- Pre-commit funding/tools for protection

- Measure outcomes (evictions, rent spikes, tenant turnover)

People also ask: “If we already upzoned, what’s the next best move?”

Answer first: Fix the conversion rate from entitlement to construction.

Upzoning is step one. The next best moves usually sit in three buckets:

- Reduce uncertainty (clear rules, faster decisions, fewer surprises)

- Reduce soft costs (streamlined review, standardized requirements)

- Target subsidies where the market won’t build the housing you need (family-sized units, deeply affordable units)

This is where AI supports public administrators: it helps teams decide which interventions produce the most additional units per euro or dollar spent.

San Francisco’s lesson for any city building a “smart” housing program

San Francisco’s plan shows political will and a willingness to adjust long-standing constraints. That’s real progress. But the story also underlines a hard truth:

A city can upzone thousands of units and still underdeliver if it doesn’t manage feasibility, permitting, and infrastructure as a single system.

For readers following our Mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā un viedajās pilsētās series, this is a strong reminder that AI’s best role in government isn’t replacing judgment—it’s making tradeoffs visible early, when you can still act.

If you’re working in a municipality, a planning agency, or a smart city program office, the most productive next step is to assess your “zoning-to-housing” toolchain:

- Do you have parcel-level data you trust?

- Can you forecast buildout under different economic conditions?

- Can you see your permitting bottlenecks in real time?

- Do you have a displacement early-warning system?

If not, that’s the work. And it’s worth doing before the next mandate arrives.

What would your city’s buildout forecast say—if it had to be updated every quarter and defended in public?