SF’s upzoning shows why zoning capacity isn’t delivery. See how AI helps cities predict housing outcomes, reduce permit delays, and target infrastructure.

AI-driven zoning: why SF’s upzoning may underdeliver

San Francisco just approved a “family zoning” plan that creates legal capacity for about 36,000 homes—yet the city’s own chief economist estimates it could yield only ~14,600 new units over 20 years. That gap isn’t a footnote. It’s the story.

Most cities are starting to learn the hard way that zoning capacity isn’t the same as housing delivery. You can rewrite height limits, expand multifamily districts, and allow extra stories near transit—and still end up with fewer cranes than expected. The reasons are familiar: financing, permitting timelines, construction costs, neighborhood litigation, infrastructure constraints, and plain old uncertainty.

For our series “Mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā un viedajās pilsētās”, this is exactly where AI belongs: not in flashy demos, but in planning, permitting, and policy operations—the unglamorous machinery that determines whether zoning reform becomes new homes or just new maps.

The core problem: “capacity” doesn’t build housing

Answer first: Zoning reform can raise theoretical housing capacity quickly, but delivery depends on market feasibility and administrative throughput.

San Francisco’s state mandate is steep: 82,000 additional housing units by 2031. The family zoning plan is partly a defensive move—keep local control rather than letting the state impose its own approach. The plan allows two to four additional stories in many areas near transit, shopping, and major streets, with high-rises limited to select locations.

So why does the forecast drop from 36,000 capacity to ~14,600 likely units? Because real-world production is constrained by a set of bottlenecks that zoning text doesn’t remove:

- Feasibility math: land + labor + materials + financing + fees must pencil out.

- Permitting and review duration: long timelines increase carrying costs and risk.

- Infrastructure readiness: water, sewer, power, schools, and transit capacity aren’t evenly distributed.

- Site assembly complexity: small parcels and fragmented ownership slow projects.

- Community conflict and uncertainty: risk premiums rise when outcomes feel unpredictable.

Here’s my stance: cities that treat zoning as the finish line are choosing underdelivery. Zoning is the starting gun.

What AI adds: from zoning documents to zoning outcomes

Answer first: AI improves housing outcomes when it’s used to predict bottlenecks, target infrastructure, and speed up decisions—not when it’s used to “automate planning” as a slogan.

The practical opportunity is to build a data-driven policy loop: you change the rules, then you continuously measure whether the change is producing permits, starts, completions, affordability, and displacement risks.

AI use case 1: Feasibility modeling at parcel level

Cities often estimate “capacity” using simplified assumptions. AI-assisted feasibility models can do better by learning from historical project data and current cost signals.

A strong model can estimate, for each parcel or block:

- probability of redevelopment within 5/10/20 years

- likely unit count and building type

- sensitivity to interest rates and construction cost indices

- the “minimum viable entitlement timeline” before projects die

This matters because policy tweaks can be targeted. If 70% of your new capacity sits on parcels that won’t pencil for decades, you don’t have a housing plan—you have a spreadsheet.

AI use case 2: Permitting triage and cycle-time reduction

Permitting isn’t just bureaucratic friction; it’s a risk multiplier. When review times stretch, financing costs rise and projects quietly disappear.

AI can help public agencies reduce cycle time without lowering standards:

- document intake and completeness checks (flag missing items early)

- plan set comparison (identify what changed between submittals)

- routing recommendations (send projects to the right reviewers faster)

- inspection scheduling optimization (reduce rework and idle time)

In smart city terms, this is classic e-pārvalde: better digital workflows, clearer status visibility, fewer dead ends.

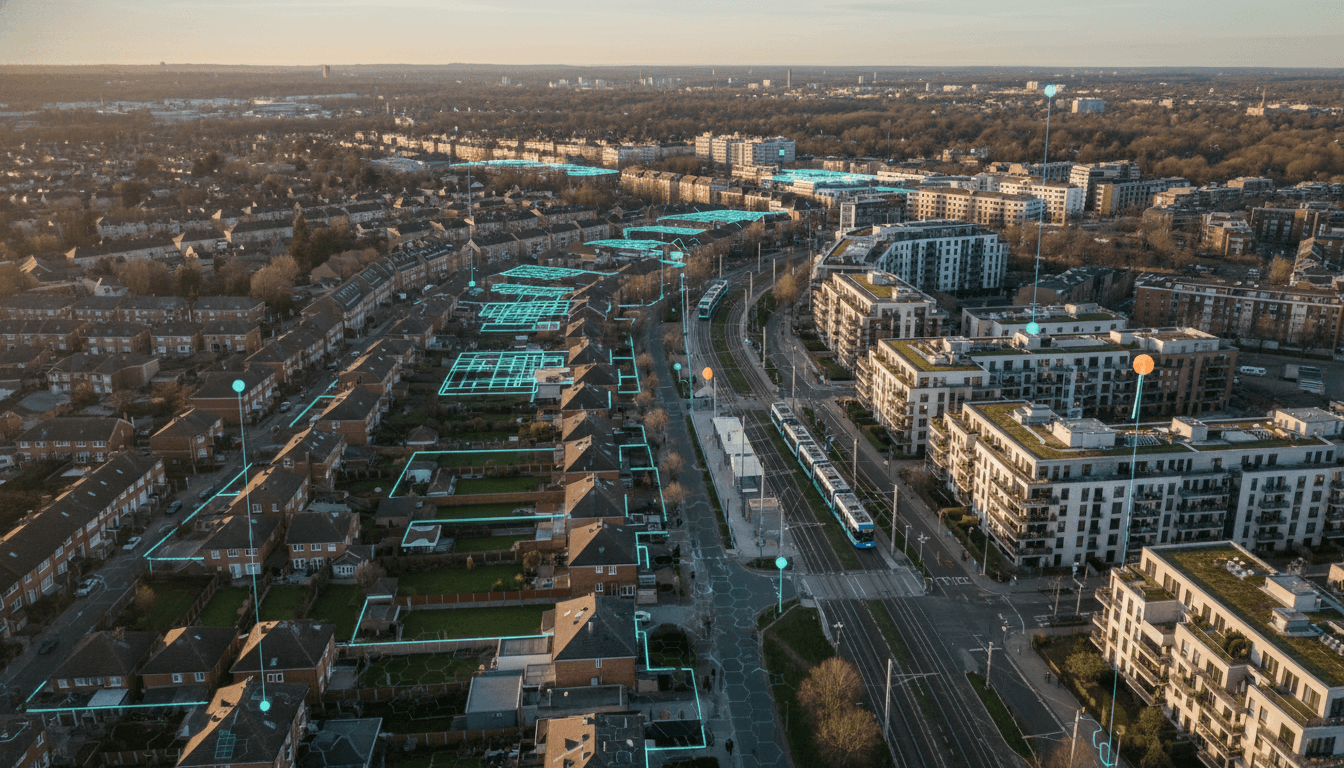

AI use case 3: Infrastructure constraint mapping (the hidden limiter)

Upzoning works best where infrastructure can absorb growth. But cities rarely have an integrated, current view of constraints.

AI-enabled planning can merge:

- utility capacity and planned upgrades

- transit service frequency and crowding

- school seat availability

- flood/fire risk layers

- emergency response coverage

Then it can produce “buildability bands” that show where additional density is realistic right now—and where capital projects must come first.

If you want 82,000 homes by 2031, you need to treat infrastructure as a production input, not a separate conversation.

The part people skip: measuring displacement risk like an operations metric

Answer first: Zoning changes can increase supply and still fuel displacement if protections and monitoring aren’t operationalized.

Critics of San Francisco’s plan warn that denser redevelopment could displace residents and that tenant protections should be stronger. Whether you agree with every critique, ignoring displacement risk is politically and ethically expensive—and it can slow housing production via backlash.

A smart city approach doesn’t hand-wave the concern away. It builds a monitoring and response system.

What a “displacement early warning system” looks like

This doesn’t require invasive surveillance. It requires joining data the public sector already touches:

- eviction filings and notices (where legally accessible)

- rent registry or advertised rent indices

- building permit patterns (demolitions, major alterations)

- property transfers and speculative flipping signals

- 311 complaints tied to construction impacts

With AI, agencies can detect hotspots and trigger actions:

- proactive tenant outreach in multiple languages

- legal aid triage and faster referrals

- targeted inspections when harassment indicators appear

- preservation acquisition strategies for at-risk buildings

This is how you keep legitimacy while adding density: treat equity as a workflow, not a press release.

Why SF’s forecast gap is a planning lesson for every city

Answer first: The 36,000-vs-14,600 gap shows why cities need an end-to-end housing delivery stack—policy, data, permitting, infrastructure, and feedback.

San Francisco’s economist still projected a positive economic impact, including GDP growth estimated between $560M and $940M from the rezoning’s effects. That’s significant, and it reinforces the central point: even partial delivery can help.

But state mandates don’t grade on effort. They grade on units.

A simple way to think about it: “Housing throughput”

If your city were a service, you’d track a funnel:

- parcels eligible under zoning

- projects proposed

- permits approved

- starts

- completions

- occupancy

Every step has leakage. AI helps you identify where and why leakage happens.

The mistake: treating housing like a one-time policy event

Cities often plan in bursts: a major rezoning, a celebratory announcement, then a slow drift into implementation chaos.

A better approach is continuous:

- weekly dashboards for permit cycle time

- monthly feasibility and cost updates

- quarterly infrastructure readiness scoring

- annual zoning calibration based on results

That’s the smart city mindset: manage the system, not the headline.

Practical playbook: how public-sector teams can apply AI to zoning reform

Answer first: Start small with high-impact operational use cases, and design for transparency from day one.

Here’s a pragmatic sequence I’ve seen work in government settings:

1) Define the outcomes (not the model)

Pick 3–5 measurable outcomes tied to housing delivery:

- median permit cycle time (days)

- conversion rate from entitlement to start

- units completed per quarter in upzoned areas

- share of projects near high-frequency transit

- displacement risk indicators in targeted areas

2) Build a shared data layer across departments

Housing delivery is cross-functional. The minimum set usually spans:

- planning/entitlements

- building and safety

- public works and utilities

- transportation

- housing department (affordability programs)

3) Deploy “copilot” tools for staff, not auto-approval

The public sector gets burned when AI is positioned as replacing judgment.

Use AI to:

- summarize project histories for reviewers

- draft applicant correction letters

- classify permit types and route them

- surface policy conflicts early

Keep the final decision with accountable officials.

4) Publish clear, human-readable metrics

Trust grows when residents can see:

- what got approved

- how long it took

- where housing is landing

- what protections exist for tenants

Transparent dashboards can reduce conspiracy thinking and improve predictability for builders.

5) Create a calibration loop

If the data shows that most “capacity” isn’t producing proposals, adjust:

- allow more by-right pathways in specific corridors

- reduce redundant review steps

- pre-approve standard building typologies

- prioritize infrastructure upgrades where the model predicts near-term delivery

Where this fits in smart city strategy (and why it matters in 2026)

Answer first: Housing is now a core smart city performance domain—because it determines labor availability, commute patterns, emissions, and service costs.

Going into 2026, cities face a familiar squeeze: high interest rates (relative to the ultra-low era), persistent construction labor constraints, and public frustration with both prices and visible homelessness. That combination makes data-driven decision-making non-negotiable.

If San Francisco’s rezoning delivers fewer units than its capacity suggests, it won’t be because the city didn’t “allow” housing on paper. It’ll be because delivery systems—permitting, infrastructure coordination, and risk management—weren’t tuned for throughput.

If you’re building policy in a municipality, a planning department, or a regional agency, the question to ask isn’t “How many units did we upzone?” It’s “How many units can we reliably deliver, and what’s our weekly plan to remove blockers?”

For public-sector teams exploring mākslīgais intelekts in e-governance and viedās pilsētas, housing is one of the highest-return areas to start—because the KPIs are concrete, the workflows are known, and the public benefit is direct.

Forward-looking question: If your city adopted a major rezoning tomorrow, do you have the data and operational capacity to prove—quarter by quarter—that it’s turning into homes?