Cities need AI data centers, but not at any cost. Learn how permitting, power, and water shape sustainable smart city AI infrastructure.

AI Data Centers vs Cities: Permits, Power, Trust

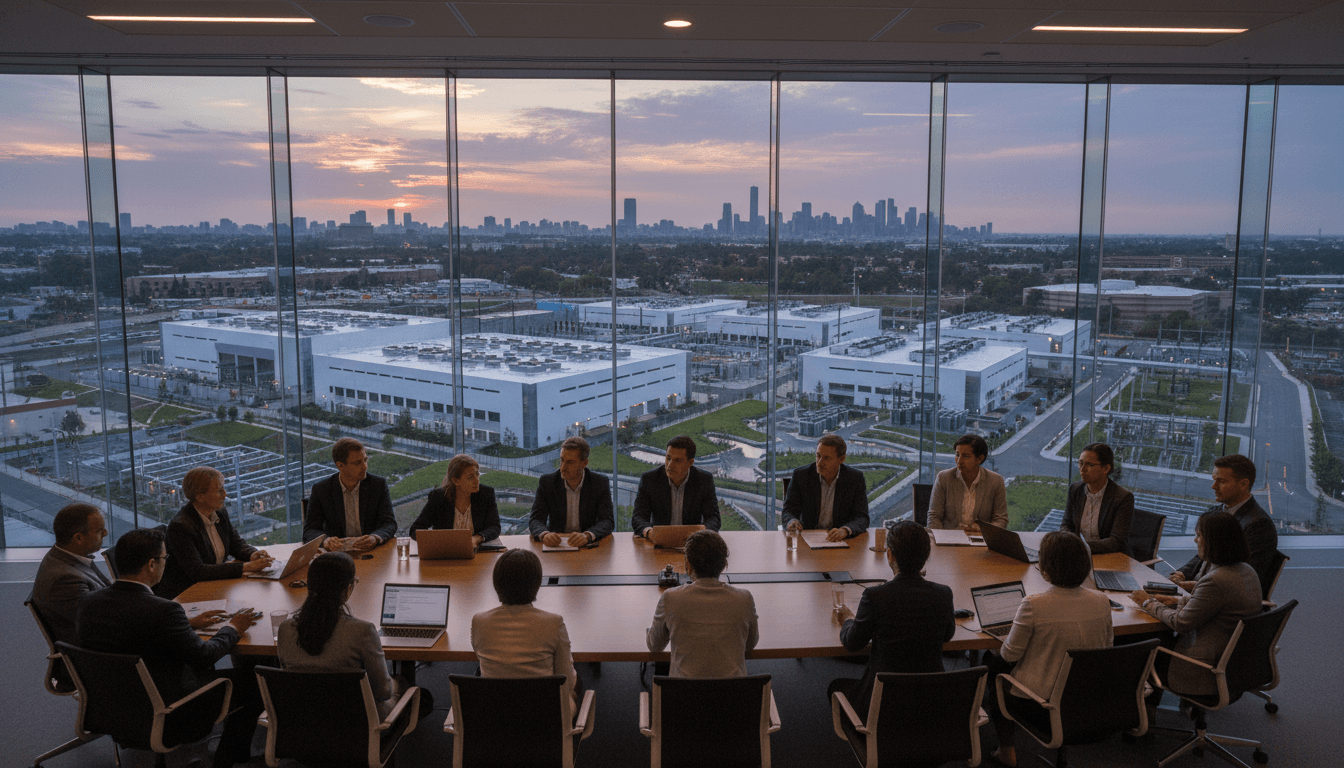

A single claim in the current U.S. debate should make every city CIO and sustainability lead sit up: tripling data centers in the next five years could consume electricity comparable to about 30 million households and water comparable to about 18.5 million households. When that scale lands inside municipal boundaries, the “AI boom” stops being abstract and becomes zoning hearings, grid upgrades, water stress, diesel generator emissions, and—most of all—public trust.

That’s why the latest move by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to streamline Clean Air Act permitting resources for data centers has triggered a very predictable counter-move: cities and counties slowing projects down with moratoriums, stricter land-use decisions, and new local standards. From the outside it looks like bureaucratic tug-of-war. From inside city hall, it’s a governance stress test.

This post is part of the “Mākslīgais intelekts publiskajā sektorā un viedajās pilsētās” series, where we focus on AI in the public sector: e‑governance, urban analytics, smart mobility, and data-driven decision-making. Here’s the uncomfortable truth I’ve seen play out: smart city AI doesn’t run on optimism—it runs on compute, power, water, and permits. If municipalities don’t plan the infrastructure and the rules, someone else will.

Data centers are now “city infrastructure,” not just tech real estate

Answer first: If your city relies on AI-enabled public services, data centers are part of your critical infrastructure footprint—even when you don’t own them.

Municipal AI workloads aren’t just chatbots. They’re video analytics for intersections, predictive maintenance for roads and water networks, emergency-response optimization, digital twins, and fraud detection in e‑services. Even when cities use cloud providers, the physical reality is the same: compute is housed somewhere, cooled somehow, powered always, and backed up with generators.

What’s changed in 2025 is the density of demand. Companies aren’t adding one facility; they’re building campuses. One example cited in recent reporting: a major hyperscaler announced $40 billion in planned investment in three new Texas data centers through 2027. Whether those exact projects are near your community or not, the pattern is widespread.

For smart city planning, that reframes a basic question:

- Are data centers a private land-use issue?

- Or are they regional utility-scale loads that reshape grid reliability, water planning, and air quality?

Cities that treat data centers like ordinary warehouses are setting themselves up for conflict later.

Why the backup generator issue keeps surfacing

Answer first: Permitting friction often concentrates around backup power because it’s where air quality, noise, fuel storage, and peak-load risk collide.

AI workloads are power-hungry and uptime-sensitive. That pushes data centers toward significant backup generation—often still diesel in many locations. That’s why the EPA’s Clean Air Act resources matter: air permitting is a bottleneck, and streamlining it can accelerate buildouts.

But from a local perspective, backup generation creates immediate, tangible concerns:

- Local NOx and particulate emissions during testing or outages

- Noise complaints (especially at night)

- Fuel logistics and spill risk

- Visual and land-use impacts near residential areas

The political reality: residents may not object to “AI.” They object to diesel smell, truck traffic, and rising bills.

The new fault line: national AI acceleration vs local consent

Answer first: Federal acceleration efforts don’t remove local pain points; they can amplify them by compressing timelines and reducing perceived local control.

In December 2025, the EPA launched a centralized resource hub to help communities and developers navigate Clean Air Act requirements for data centers and their stationary sources. The stated intent is increased certainty and faster development.

At nearly the same moment, a coalition of 230+ organizations called for a nationwide data center moratorium until standards address environmental and social impacts. That’s not a small protest. It’s a signal that the public narrative has shifted from “tech investment” to “community burden.”

Add a broader federal push for AI-forward policy—including an executive posture that discourages state-level AI restrictions—and you get a predictable municipal response: if cities can’t control AI policy, they’ll control land, utilities coordination, and permitting conditions.

In other words, local government’s strongest levers aren’t always “AI laws.” They’re:

- Zoning and conditional use permits

- Noise ordinances

- Building codes and fire code enforcement

- Water connection approvals and industrial pretreatment requirements

- Local procurement rules (when cities buy cloud/compute)

What “cooperative federalism” feels like on the ground

Answer first: It’s cooperative until the community thinks the costs are being externalized.

When residents see wholesale power prices rising near data center clusters—one report cited increases as high as 267% versus five years earlier in certain areas—local leaders get pressured to intervene. U.S. Senators have also announced investigations into whether data center costs are being shifted to households.

Even if your city isn’t in those exact hotspots, the story travels fast:

“Are we going to pay more so a private campus can run AI training?”

Municipal leaders don’t survive by answering that with jargon.

The hidden municipal cost stack: power, water, and equity

Answer first: The core risk isn’t that data centers exist; it’s that cities approve them without enforceable performance terms that protect residents.

Smart city programs often pitch benefits—safer streets, smoother traffic, faster services. Data centers flip the lens to inputs.

Power: reliability, peak load, and who pays

Data centers create a persistent base load. In constrained grids, that can drive:

- More peaker plant operation (higher emissions)

- Transmission and substation upgrades

- Reliability planning changes (and political fights about siting)

From a governance angle, the “who pays” question is the center of the argument. If grid upgrades are socialized into rates, residents feel it immediately. Cities should demand clarity on:

- Interconnection upgrade costs and timelines

- Demand response participation

- On-site storage and peak shaving commitments

- Reporting on actual vs forecasted load

Water: not just consumption, but seasonal conflict

Cooling water is often where community conflict becomes emotional—especially during drought cycles or winter infrastructure strain. December 2025 is exactly when many cities finalize next-year capital plans; approving a major new industrial water load without a multi-year supply and resilience model is asking for trouble.

A practical stance I support: if a project can’t disclose its cooling approach and water intensity up front, it isn’t ready for approval.

Equity: when benefits are regional and burdens are local

A data center might bring property tax revenue and some jobs, but the heaviest impacts are local:

- Noise and truck routes

- Air emissions from backup generation

- Land price pressure and industrial creep

That mismatch is why some communities are moving toward slower approvals or outright rejection of applications.

A smarter permitting playbook for AI-enabled cities

Answer first: Cities don’t need to “ban” data centers to protect residents—they need enforceable standards tied to measurable outcomes.

Moratoriums can be a useful pause button, but they’re blunt. The better long-term move is a permitting framework that recognizes data centers as AI infrastructure with public impacts.

1) Require an “AI infrastructure impact statement”

Make developers submit a standardized package, similar in spirit to traffic impact studies:

- 24/7 load forecast (1-, 3-, 5-year)

- Peak demand profile and planned demand response

- Cooling method, annual water forecast, drought contingency

- Backup power inventory (fuel type, testing schedule, emissions controls)

- Noise modeling and mitigation design

- Construction logistics plan (routes, hours, staging)

The goal is simple: no surprises after the first outage or the first heat wave.

2) Tie approvals to measurable performance terms

Cities can negotiate conditions that are concrete and enforceable:

- Limits on generator testing hours and noise thresholds

- Requirements for cleaner backup power (renewable diesel, gas with controls, battery storage, or hybrid systems)

- Water reuse targets (where feasible) or seasonal caps

- Participation in grid support programs (demand response, curtailment)

- Transparency reporting (quarterly energy and water usage ranges)

If you can’t measure it, you can’t govern it.

3) Design for heat waves and grid stress—explicitly

AI compute demand doesn’t politely pause during extreme weather. Cities should ask:

- What happens during a regional heat wave when the grid is constrained?

- Will cooling loads spike precisely when residential cooling peaks?

- Will backup generation run for hours—or days?

A city that plans smart mobility and emergency response should treat data centers the same way: stress-test the system, not the brochure.

4) Connect data center approvals to smart city public value

Here’s the contrarian take: if a city is going to host AI infrastructure, it should get more than generic tax revenue.

Negotiable community benefits can include:

- Heat mapping or traffic analytics support for public agencies

- Emergency compute capacity reservations during disasters

- Workforce pathways with local colleges for operations and electrical trades

- Funding for substation hardening or microgrid pilots serving critical facilities

This isn’t charity. It’s governance: aligning private infrastructure with public outcomes.

“People also ask” (and what I’d answer in a council meeting)

Do data centers automatically make a city “smarter”?

No. They make AI possible at scale, but smartness comes from how cities use data, improve services, and protect rights. Infrastructure is necessary, not sufficient.

Are local moratoriums anti‑AI?

Not necessarily. They’re often pro‑planning. A short moratorium can be the only way to write standards before approvals become irreversible.

What’s the fastest win for municipalities?

Create a single, cross-department review path (planning + utilities + environment + emergency management) and publish clear requirements. Developers hate uncertainty; residents hate secrecy. A transparent process reduces both conflicts.

Where this lands for AI in the public sector (and what to do next)

The backbone of AI-enabled urban management is being built right now, often faster than cities can update plans. The EPA’s push to streamline permitting resources signals one direction: accelerate. Local governments pushing back signals another: slow down until impacts are understood.

If you’re responsible for e‑pārvalde, smart mobility, or AI-driven urban analytics, don’t treat this as someone else’s fight. Your digital strategy has a physical footprint. When cities align data center development with energy, water, and air-quality guardrails, they protect residents and still make room for innovation.

If you want a practical next step: draft a two-page “data center standards” checklist your planning department can actually use, then pilot it on the next application. After that, the bigger question becomes unavoidable—and worth debating publicly: what does “AI-ready city” mean when residents also demand “affordable bills, clean air, and reliable water”?