AI data centers are exploding in number—and in water use. Here’s how smart siting, dry renewables, and better cooling can make them truly green.

Most people know AI is energy-hungry. Fewer realize it’s also water‑hungry. In 2023, U.S. data centers used roughly 17 billion gallons of water on‑site for cooling — but more than 211 billion gallons indirectly through the power plants that feed them. That imbalance is the real story: over 70 percent of a data center’s water footprint usually comes from the grid, not the cooling towers.

This matters because AI adoption is exploding right now, and so is the global push for green technology. If your company is betting on AI and digital infrastructure, how you build and where you build will decide whether you’re part of the climate solution or quietly worsening water stress.

The reality? Designing water‑smart data centers is simpler than you think — if you stop treating water, energy, and location as separate decisions.

In this post, I’ll break down what the latest research is telling us about “thirsty” data centers, why location and energy mix are the biggest levers you have, and what practical steps operators, policymakers, and sustainability teams can take to make AI infrastructure genuinely sustainable.

Why data centers use so much water

Data centers consume water in two main ways: direct cooling and indirect power generation. The second one is usually much bigger.

Direct water use: keeping servers alive

On-site, water is mostly used for cooling:

- High‑density servers generate a lot of heat.

- Chilled water or evaporative cooling systems pull that heat away so equipment doesn’t fail.

- Some sites also use water for humidification and building HVAC.

This is the part communities see: new data centers applying for water permits, or local headlines about millions of gallons per day. It’s real, and in some regions it’s already political.

Indirect water use: the hidden footprint in the grid

The larger slice of the pie is off‑site water use embedded in electricity. Here’s where the numbers get uncomfortable:

- In many regions, electricity still comes predominantly from thermoelectric power plants (coal, gas, nuclear).

- These plants burn fuel to heat water into steam, spin turbines, then cool and condense that steam. That cooling step takes huge amounts of water.

- Hydropower has its own water footprint: large reservoirs lose enormous volumes to evaporation.

Cornell researchers found that more than 70% of a typical data center’s water use comes from electricity generation, not cooling towers on the property. So if you only optimize on‑site water use, you’re working on the smaller half of the problem.

If your sustainability dashboard only tracks “liters per kWh” on-site, you’re undercounting your real impact.

For green technology to live up to its name, AI infrastructure has to account for both.

The core insight: where you build changes water use by 100x

The Cornell study on U.S. data centers makes one thing crystal clear: location is a climate and water decision.

The researchers modeled direct and indirect water and energy use for data centers across the country and found that environmental impacts can vary by up to a factor of 100 between locations. Same size data center, same load — radically different outcomes.

Why “dry renewables” beat “wet power”

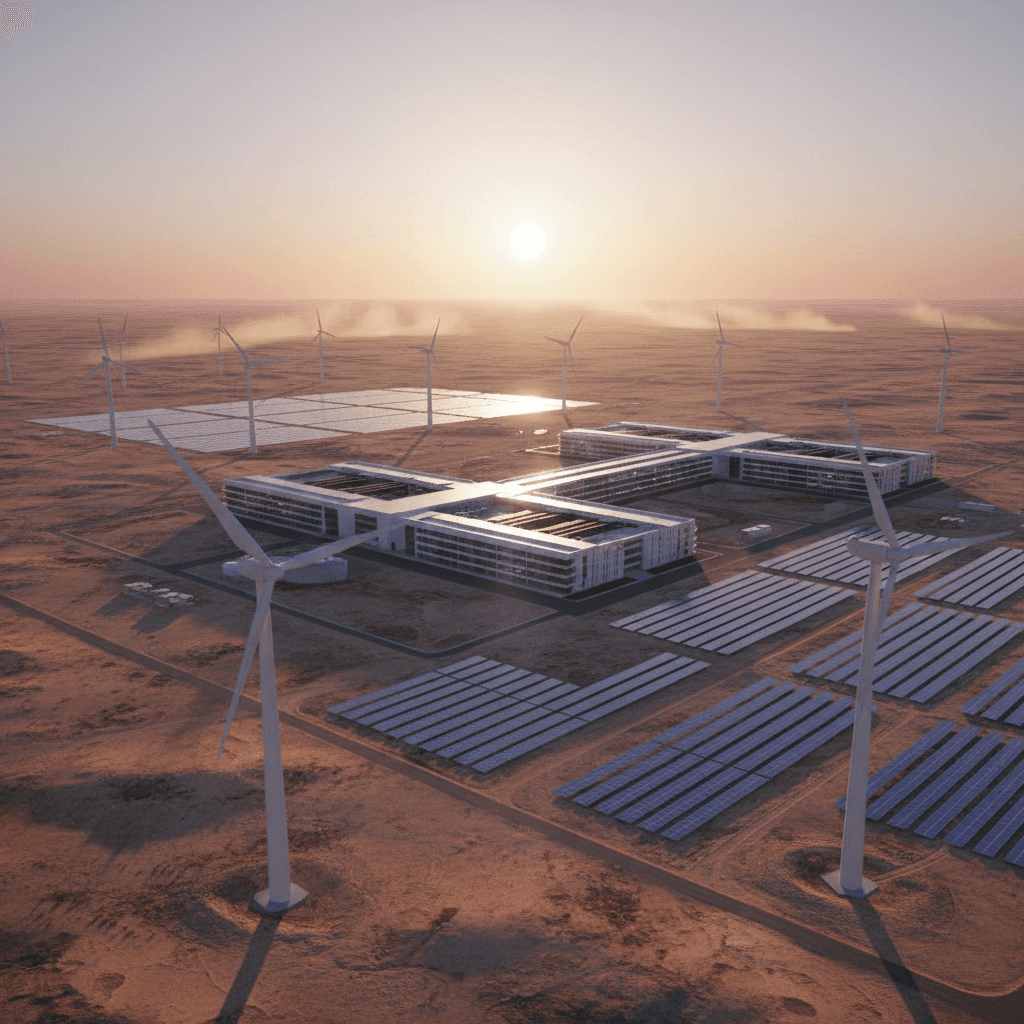

The lowest‑water data centers share one trait: they sit on grids dominated by wind and solar, sometimes backed up by gas or other sources, but with minimal reliance on water‑intensive plants.

Wind and solar are often called “dry renewables” because they produce electricity with virtually no ongoing water use. That’s a massive advantage over:

- Coal and gas plants with once‑through or recirculating cooling

- Nuclear plants with large cooling needs

- Hydropower with big reservoir evaporation losses

So the trick isn’t just “use renewables.” It’s use low‑water, low‑carbon renewables.

The surprising winners: West Texas and the “wind belt”

Cornell’s analysis highlights some locations that don’t fit the traditional data center playbook:

- West Texas – One of the lowest grid‑related water footprints in the country thanks to huge wind build‑out and relatively low population density. Groundwater can support cooling if managed responsibly.

- Nebraska, South Dakota, Montana – Similar profile: high wind and solar potential, low current water stress in many areas, and space to grow.

From a pure energy + water efficiency perspective, these states are among the best places in the U.S. to host AI servers.

The counterintuitive losers: the hydropower‑rich Northwest

By contrast, much of the Pacific Northwest scores poorly on water footprint despite cheap, low‑carbon electricity. The culprit is hydropower’s evaporation losses from large reservoirs.

So you end up with this trade‑off:

- Carbon: Northwest hydropower looks great.

- Water: It’s often worse than a wind‑dominated grid.

This is where a mature green technology strategy has to move beyond single metrics. Carbon alone isn’t enough; carbon + water + location is the new baseline.

How AI and cloud leaders are already shifting

The big players aren’t ignoring this. If anything, they’re a few steps ahead of most policymakers.

Siting around water stress

A separate study from Purdue University looked at Google’s U.S. data centers and overlaid them with current and projected water stress. Their conclusion: most of Google’s existing data centers are already in lower‑stress regions.

That doesn’t happen by accident. When sites represent billions in capital and decades of operation, you don’t want to gamble on running out of water or facing community backlash.

I’ve seen more RFPs and site‑selection briefs in the last two years that explicitly ask for:

- Long‑term water availability and rights

- Projected water stress under climate scenarios

- Local groundwater and surface water governance

- Nearby renewable energy build‑out potential

It’s not just about risk avoidance either. There’s a brand and talent dimension: “thirsty AI” is bad PR in 2025, especially if you’re building in regions already battling drought.

Water‑positive, not just carbon‑neutral

The next frontier for credible green technology is going beyond neutral:

- Carbon‑neutral → 24/7 carbon‑free power

- Water‑neutral → water‑positive, where companies restore more water to stressed basins than they withdraw

Several hyperscalers are already committing to balancing or exceeding their water withdrawals through watershed restoration, agricultural efficiency projects, and urban reuse. Siting in low‑stress, wind‑heavy regions makes those commitments far cheaper to fulfill.

Practical steps to make data centers less thirsty

If you’re planning, operating, or regulating AI and cloud infrastructure, you have more levers than you might think. Here’s how to use them.

1. Treat water footprint as a first‑class siting criterion

Site selection usually starts with land prices, tax incentives, fiber routes, and grid capacity. Those still matter. But the research is blunt: if you ignore water and energy mix, you’re locking in avoidable impacts for decades.

At minimum, put these questions on page one of any site‑selection brief:

- What’s the current and projected water stress at this location?

- What’s the grid mix now and in 10–20 years? How much is wind/solar vs. coal, gas, nuclear, hydro?

- What’s the water use per MWh of the local grid compared with other candidate sites?

- Can we sensibly add new wind/solar capacity tied to this site (PPAs, direct investment, or co‑location)?

If two sites are similar on cost and latency, the one with a drier grid is almost always the smarter long‑term bet.

2. Decarbonize and dry out your energy supply

Green technology strategies that focus only on carbon can unintentionally increase water risk — for example, by leaning heavily on nuclear in arid regions or oversizing new reservoirs.

A better approach is to prioritize “dry” low‑carbon power:

- Wind and solar as the primary growth sources where feasible

- Battery storage to firm those renewables instead of defaulting to new gas peakers

- Grid‑aware workloads that shift flexible compute to regions with surplus wind/solar

For AI workloads, this is especially powerful. Training runs and some inference jobs are time‑flexible and location‑flexible. That’s a gift: you can literally move part of your water footprint to a better grid.

3. Use smarter cooling, especially in dry, windy regions

Siting in West Texas or the northern plains doesn’t give you a free pass on direct water use. You still have to be thoughtful.

Options that work particularly well in dry, windy climates:

- Air‑side and adiabatic economization – Use outside air when conditions allow; add minimal water when you need extra cooling.

- Hybrid cooling systems – Switch between water‑based and air‑based operation depending on temperature, humidity, and grid conditions.

- Closed‑loop water systems – Reduce withdrawals and avoid once‑through cooling.

- Non‑potable sources – Reclaimed wastewater, industrial effluent, or brackish groundwater instead of drinking water.

Pair those with tight monitoring, and you can support high‑density AI racks without stressing local utilities.

4. Make water, carbon, and energy visible to decision‑makers

One of the biggest gaps I see is organizational: sustainability teams have water and carbon dashboards; infrastructure teams have uptime and cost dashboards; finance has an ROI sheet. They often don’t talk to each other early enough.

Fix that by building integrated metrics that matter to all three:

- kWh per AI inference or per training run

- Grams of CO₂e per kWh at the actual time and place workloads run

- Liters of water per kWh including grid‑embedded water

- Projected water risk cost (e.g., probability‑weighted cost of curtailment, permits, community pushback)

Once those numbers sit next to each other in board decks and capex approvals, siting and architecture decisions start to shift.

5. Use policy and incentives to steer the boom

For policymakers in states like Nebraska, South Dakota, or Montana, the Cornell results are basically a strategic memo.

If you want green technology jobs without draining rivers:

- Streamline permitting for data centers that commit to dry renewables + water‑efficient cooling.

- Offer tax incentives tied to water and carbon performance, not just headcount.

- Invest in transmission lines that unlock high‑quality wind and solar resources near data center hubs.

- Require transparent reporting on water withdrawals, discharges, and grid mix.

Most companies building at scale will go where the policy environment is clear and supportive. If you design it around low‑water AI infrastructure, that’s what you’ll attract.

Why this matters for the future of green technology

The green technology story isn’t just about swapping fossil fuels for clean energy. It’s about building digital infrastructure that respects physical limits — especially water.

AI is going to underpin smart grids, climate modeling, agriculture optimization, and more. It makes no sense for the core compute that drives those solutions to quietly worsen drought risk.

There’s a better way to approach this:

- Put data centers where wind and solar are abundant and water stress is low.

- Design them with efficient, flexible cooling systems that use non‑potable water where possible.

- Power them with dry renewables so both carbon and water footprints drop together.

- Align corporate strategies and public policy so the AI boom strengthens, instead of strains, local communities.

If your organization is scaling AI right now, this isn’t a theoretical question. The siting decisions you make over the next 12–24 months will shape your environmental footprint for decades.

So the real question is: Will your AI infrastructure be part of the water problem — or a model for how green technology can grow without drying out the places we live?