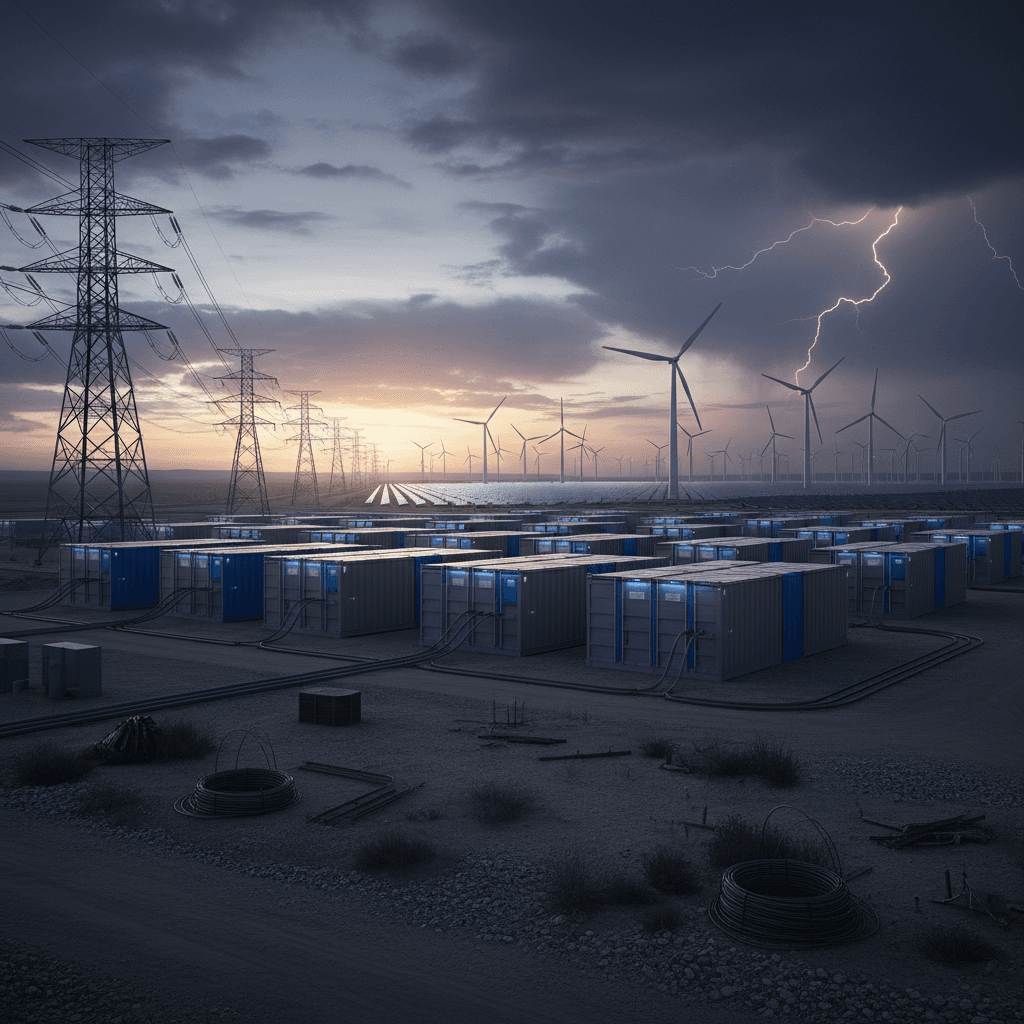

NGK just shut down the world’s second‑most‑deployed grid battery. Here’s what that means for long‑duration storage, green technology strategy, and your next project.

Most people in energy thought sodium‑sulfur would be part of the grid for decades. Then, at the end of October, NGK’s board voted to stop making NAS batteries and stop taking new orders.

For the second‑most‑deployed grid battery technology on the planet, that’s not a minor footnote. It’s a warning shot about how hard it is to commercialise long‑duration energy storage and how quickly the landscape of green technology can shift.

This matters because the decarbonisation plans on everyone’s slide decks — utilities, data centres, heavy industry, even city planners — all quietly assume that long‑duration storage will be there when they need it. NGK’s decision shows that technology alone isn’t enough. Business models, finance, risk appetite and timing can make or break even a proven, 20‑year‑lifetime battery.

In this Green Technology series, I’ll break down what NGK’s NAS exit really means, what it tells us about green energy storage economics, and where AI‑driven planning and control can help you avoid getting stranded on the wrong side of the next technology shift.

What just happened to sodium‑sulfur batteries?

NGK Insulators has officially discontinued manufacturing and sales of its sodium‑sulfur (NAS) grid battery line and stopped taking new orders. The company will keep servicing existing sites, but the technology is effectively frozen.

That’s a big deal because NAS wasn’t a fringe experiment:

- >5GWh deployed globally since 2003

- Longest‑serving grid‑connected battery tech at utility scale

- Second‑most‑deployed grid storage battery after lithium‑ion

- Most‑deployed long‑duration battery so far, after pumped hydro

Technically, NAS has a lot going for it:

- 6+ hour discharge for real long‑duration use cases

- 20‑year lifetime, with <1% degradation per year claimed

- Made from abundant materials: sodium, sulfur, steel, aluminium

From an engineer’s perspective, that’s a solid green technology story: long life, stable performance, and no dependence on lithium or cobalt.

So why shut it down? In one line: the business case never reached the scale the technology deserved, and a key partner, BASF, walked away before the economics could flip.

Why NGK pulled the plug: it wasn’t about the physics

The core problem wasn’t that NAS didn’t work. It did, at commercial scale, across Japan, the UAE, Europe, and now pilots in the US.

The problem was the industrialisation step between “proven tech” and “global commodity product”.

The BASF partnership and the scale gap

In 2019, NGK partnered with BASF with a clear objective: build gigawatt‑hour‑scale manufacturing, slash costs by about 50%, and push NAS into mainstream grid projects.

BASF did more than sign an MOU:

- Rebranded its “BASF New Business” arm to BASF Stationary Energy Storage

- Worked with regional partners like Leader Energy in Southeast Asia

- Supported deployments in Europe (Bulgaria, Germany) and beyond

From a green technology lens, this was the classic play: pair deep technical IP (NGK ceramics and NAS chemistry) with global industrial muscle (BASF) to bring a lower‑impact, long‑duration storage technology to scale.

Then the CEO changed. The new leadership at BASF refocused on core segments and pulled investment from stationary storage. No gigafactory, no cost curve, no path to true price competitiveness.

NGK tried to replace BASF with new investors. One came close, then walked away amid rising risk aversion to upstream battery manufacturing, especially after the collapse of European lithium‑ion hopeful Northvolt. In that environment, investors preferred funding downstream projects using proven, bankable tech — mostly lithium‑ion — over taking risk on a factory for a specialist battery chemistry.

From there, the decision was almost inevitable: a low‑volume, capital‑intensive product line contributing around 1% of NGK’s total sales simply couldn’t justify the ongoing investment.

The lesson: green technology lives or dies at the intersection of chemistry, cash flow, and courage. You can’t ignore any of the three.

What NAS tells us about long‑duration energy storage (LDES)

Long‑duration energy storage is the missing middle between short‑duration lithium‑ion batteries and huge assets like pumped hydro and hydrogen. NAS was one of the few commercially deployed technologies in this space.

Where NAS was actually strong

In real projects, NAS shined in a few specific roles:

- 6–10 hour shifting of renewable energy: soaking up excess solar or wind and releasing it into evening peaks

- Grid support in harsh conditions: high‑temperature operation and robust materials worked well in places like the UAE

- Long‑life, low‑degradation scenarios: where cycling patterns and long asset life mattered more than ultra‑low upfront $/kWh

Use cases included:

- A 648MWh multi‑site system in the UAE for grid stability and renewable integration

- A 70MWh installation in Japan participating in energy trading markets

- Projects in Bulgaria and Germany, including integration with green hydrogen

- A Duke Energy pilot in the US, positioning NAS as a long‑duration option for utilities

From a climate perspective, that’s exactly the sort of portfolio we need to enable higher renewable penetration without leaning entirely on fossil backup.

Why long‑duration keeps struggling commercially

NAS is not the only long‑duration storage tech facing headwinds. The pattern is familiar:

- Revenue models are immature: Markets still pay best for fast frequency response and short‑duration arbitrage — areas where lithium‑ion dominates.

- Policy signals are vague: Most countries have decarbonisation targets but few have specific, bankable incentives for 6–12 hour+ storage.

- Financiers prefer what they know: Lenders and infrastructure funds are set up to underwrite gigawatts of lithium‑ion, not niche chemistries with limited track records.

- Manufacturing scale is chicken‑and‑egg: You need scale to cut costs, but you need low costs to justify the scale.

NAS hit every one of those barriers. The technology didn’t fail; the ecosystem around it wasn’t ready.

What this means for utilities, developers and climate‑focused businesses

If you’re planning large‑scale renewables, data‑centre capacity, or industrial decarbonisation, NGK’s exit is a reminder to get brutally honest about technology risk.

1. Don’t bet everything on a single storage chemistry

Lithium‑ion will dominate short‑duration storage for the rest of this decade. That’s just reality. But for green technology strategies that stretch beyond 2–4 hour applications, you can’t simply “wait for the perfect LDES”.

Practical moves:

- Design portfolios, not silver bullets: Combine lithium‑ion, demand response, thermal storage, and where appropriate, emerging LDES on pilot scale.

- Match asset life and use case: For 20‑year grid assets, a chemistry with slow degradation can be attractive even if $/kWh is higher, provided the revenue stack is robust.

- Treat non‑lithium assets as strategic experiments: Limit exposure, but don’t avoid them entirely. You’re buying learning as well as capacity.

2. Stress‑test storage choices against business scenarios

One thing I’ve seen work well is to treat storage technology selection as a full business case exercise, not just an EPC decision.

Run scenarios like:

- "What if my supplier exits the market in 5–10 years?"

- "What if my main revenue source (e.g. frequency response) gets saturated?"

- "What if policy finally prices long‑duration capacity correctly — can I expand or retrofit?"

Here’s where AI and digital twins earned their place in the green technology toolbox:

- Use AI‑based planning tools to simulate different storage mixes against historical and synthetic demand/price data.

- Model degradation and O&M under various operating strategies.

- Optimise dispatch under multiple market rules to estimate upside and downside.

The goal is simple: if a specific technology line disappears — like NAS just did — you’re inconvenienced, not paralyzed.

3. Demand transparency from storage vendors

In the NAS story, the decision point was clear: BASF pulled investment, NGK announced the shutdown, and existing customers were told service would continue. That’s responsible.

When you negotiate new storage projects today, especially with non‑lithium providers, push for:

- Clear commitments on long‑term service and spare parts

- Technology roadmap disclosure: what’s in R&D, what’s at risk

- Exit and retrofit strategies if manufacturing stops

If a vendor can’t talk openly about these, treat that as a red flag.

Where green storage goes next: beyond NAS

NAS stepping back doesn’t mean long‑duration storage is doomed. It means we’re still in the selection phase of which green technologies will scale.

Right now, a few trends stand out:

- Thermal and “sand” batteries for district heating and industrial processes

- Compressed air and liquid air energy storage for bulk, long‑life capacity where geology or space allows

- Flow batteries and metal‑air systems trying to find their economic niche

- Hydrogen and hybrid hubs combining electrolysers, batteries, and flexible generation

What ties these together is that none of them win on chemistry alone. They win when they integrate into:

- Smarter markets that value long‑duration capacity

- Grid‑aware AI control systems that squeeze every revenue stream possible

- Urban and industrial planning that sees storage as core infrastructure, not an add‑on

NGK’s European strategy lead put it bluntly: NAS was a “great technology” in the “wrong environment, in the wrong time.” I agree with that. The tech wasn’t misaligned with climate goals; the market design was.

If you care about green technology not just as a buzzword but as a working system, this is the signal: we need to fix the environment so the next NAS doesn’t die on the vine.

That means:

- Policy that explicitly values 6–12+ hour storage

- Project developers who design around system needs, not just today’s markets

- Investors willing to back factories, not just projects

And underneath all of that, better intelligence: AI tools that can prove, in numbers, why a specific mix of storage technologies delivers more reliability, lower emissions, and better returns than yet another copy‑paste lithium project.

Where you go from here

NGK’s NAS exit is a reality check for anyone planning serious decarbonisation: technology maturity doesn’t guarantee commercial survival. You need a view not just on what works, but on what’s likely to stay bankable for the next 10–20 years.

If you’re a utility, developer, or sustainability leader, the next step isn’t to avoid long‑duration storage. It’s to treat it as a strategic asset class that deserves proper modelling, careful exposure, and clear governance.

Build a roadmap where:

- Lithium‑ion handles today’s fast‑moving markets

- Emerging long‑duration options are piloted where they best fit

- AI‑driven planning and control make the economics visible and defensible

The energy system we need in 2035 simply doesn’t work without long‑duration storage. The question is which technologies will still be standing — and whether your organisation will have positioned itself to use them rather than react to them.