Robots can now throw 70mph and catch at short range. Here’s what that reveals about AI robotics, dynamic manipulation, and automation ROI.

Robots Throw 70mph: What It Means for Industry AI

A baseball thrown at 70 mph covers the distance from pitcher to batter in a blink. Now picture a robot doing that—then catching and batting at short range with reaction windows that leave almost no time for correction. That’s not a party trick. It’s a stress test for the exact capabilities industry has been chasing for a decade: fast perception, precise control, safe physical interaction, and repeatability under uncertainty.

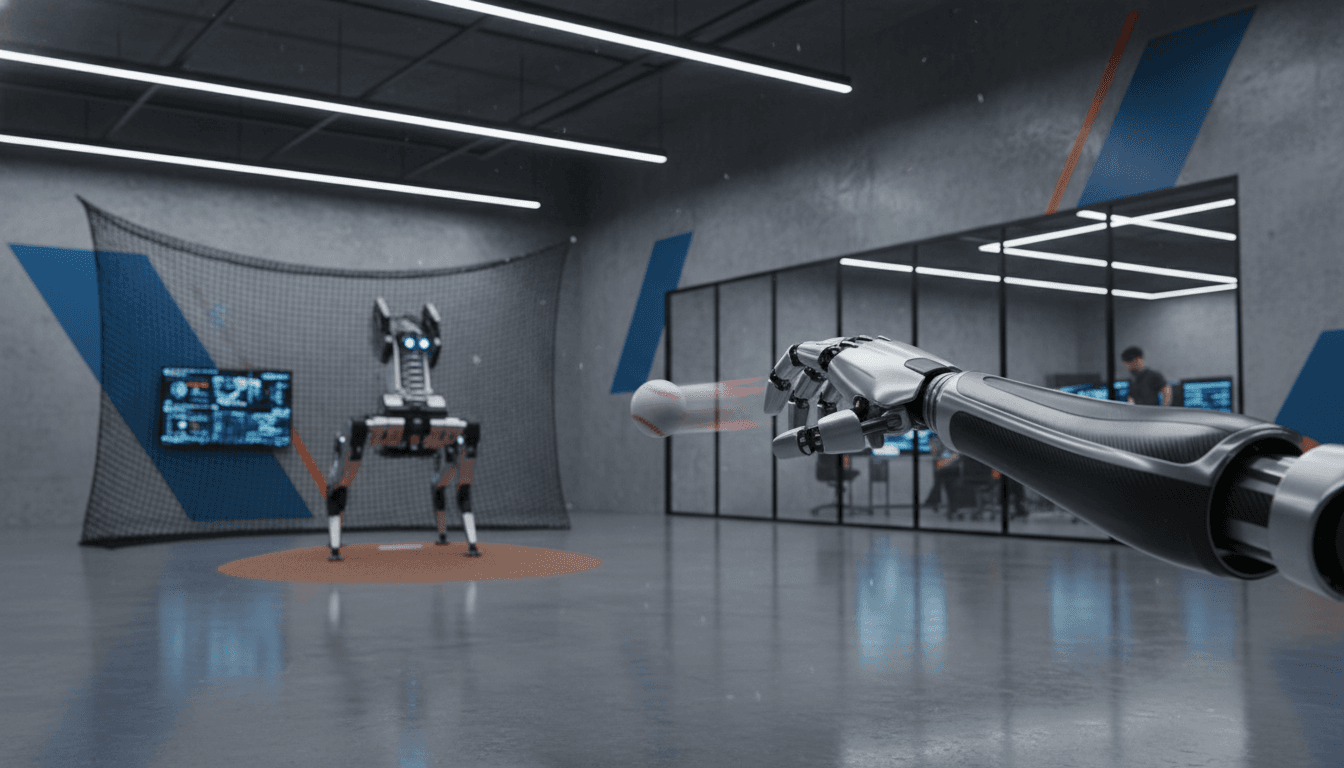

In a recent robotics roundup, researchers at the RAI Institute showed a low-impedance robot platform playing catch and doing batting practice with other robots and skilled humans. The numbers are the headline—70 mph throws, catching balls up to 41 mph at about 23 feet (7 m), and hitting pitches around 30 mph—but the real story is what those numbers imply for factories, warehouses, healthcare, and field robotics.

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and I’m going to take a clear stance: sports robotics demos are one of the most honest windows into whether AI-powered robotics is ready for dynamic, real-world work. If a system can track, predict, and physically respond to a fast-moving ball, it’s much closer to handling the messy variability of packages, parts, tools, and people.

Robotic baseball is a proxy for “real work”

Robots playing baseball looks playful, but the underlying demands map tightly to real operational problems. Baseball forces a robot to do three hard things at once: perceive quickly, plan under time pressure, and move with controlled compliance.

In industrial automation, many deployments still live in “structured comfort”: fixed part presentation, controlled lighting, predictable timing, guarded cells. Baseball is the opposite. The ball doesn’t arrive in exactly the same place twice, and you can’t pause mid-flight to rethink your plan. That’s why I like these demos: they expose the real bottleneck—dynamic manipulation.

What the RAI Institute demo signals

The RAI Institute work highlights a platform built around low impedance, meaning the robot’s joints and control strategy are designed to be more backdrivable and compliant, rather than stiff and forceful. Stiffness is great for certain tasks (like heavy machining), but stiffness can be dangerous when interacting with humans or fragile items—and it struggles with impacts.

A baseball catch is an impact management problem. So is:

- catching a shifting parcel in a high-speed sortation line

- inserting parts when tolerances vary slightly

- handling food items without bruising

- assisting a nurse without jostling a patient

The sports framing makes it easy to watch. The engineering reality is industrial.

Why the speed numbers matter

Let’s translate the demo metrics into capability signals:

- 70 mph throws: high-end joint speed, torque control, and timing accuracy.

- 41 mph catches at 23 feet (7 m): short time-to-contact, demanding prediction (you can’t just react after the ball is “close”).

- Batting at short distances: precision at the moment of impact and robustness to variation.

These are exactly the ingredients behind reliable human-robot collaboration where humans shouldn’t need to slow down just because a robot is nearby.

Low-impedance robots: the control approach industry keeps circling back to

Low-impedance control is one of those ideas that keeps resurfacing because it fits the real world: environments push back. Objects slip. People bump into systems. Tools vibrate. If your robot can’t yield safely and still maintain performance, you end up over-guarding it—losing most of the productivity upside.

The “secret” behind dynamic manipulation isn’t one secret. It’s a stack.

The stack behind a robot that can throw, catch, and hit

A practical dynamic manipulation stack usually includes:

- High-rate sensing and state estimation (vision + proprioception)

- Prediction (ballistic tracking, learned dynamics, or hybrid models)

- Motion planning under tight deadlines (often approximations, not perfect plans)

- Torque control / impedance control (to manage contact and impact)

- Recovery behaviors (what the robot does when it’s wrong)

That fifth item is where most demos hide the pain. Real deployments don’t fail because the robot can’t do the “happy path.” They fail because the robot can’t recover without a human babysitter.

“Soft falling” research is not a gimmick—it’s uptime

One piece from the roundup that deserves more attention: research demonstrating controlled, soft falls, even for bipedal robots, using a robot-agnostic reward function balancing end pose goals with impact minimization and protection of critical parts.

That sounds academic until you consider what falling means in operations:

- A fallen robot can shut down a line.

- A fall can damage expensive actuators.

- Unsafe falls can injure nearby workers.

If humanoids and legged robots are going to leave the lab and operate in warehouses, hospitals, and construction sites, “how it falls” becomes a reliability feature, not a blooper reel.

From baseball to the factory floor: where this capability pays off

Dynamic manipulation isn’t about making robots look human. It’s about making robots useful in the places traditional automation struggles.

Manufacturing: when parts aren’t presented perfectly

Many manufacturers still rely on fixtures, trays, and careful part orientation because robots prefer certainty. But the business wants flexibility: smaller batch sizes, faster changeovers, and less tooling.

A robot that can catch a baseball at speed is demonstrating key prerequisites for flexible manufacturing:

- real-time pose estimation

- rapid re-planning

- controlled contact

That translates to tasks like bin picking with variation, force-limited assembly, and tool handoffs.

Logistics: handling variability at throughput

Warehouse automation has improved, but the hard part remains: unstructured manipulation at speed. Conveyors don’t politely wait. Packages deform. Labels peel. Items jam.

That’s why I laughed (and agreed) with the commentary about “lights-out” videos: the real test isn’t whether a robot can pick for 60 seconds on camera—it’s whether it can keep performance for hours with minimal interventions.

Dynamic manipulation research moves the needle by reducing the frequency and severity of “exception cases,” which is where labor gets pulled back into an automated process.

Healthcare and emergency response: fast decisions, limited resources

The roundup also highlighted DARPA’s Triage Challenge, aimed at improving medical triage in mass casualty incidents where resources are limited. While triage isn’t baseball, the shared problem is clear: time pressure + uncertainty + human safety.

AI-powered robotics in healthcare is not just about hospital delivery robots. The higher-value frontier is assistance in environments where staff are overwhelmed:

- moving supplies reliably

- assessing patients with sensors

- supporting clinicians with decision systems

The best robotics programs treat safety and robustness as first-class requirements, not afterthoughts.

The humanoid conversation: impressive demos vs. deployable value

Humanoid robots showed up repeatedly in the roundup—acrobatics, factory-floor discussions, and debates about generalization in manipulation. Here’s my stance: humanoids aren’t “the point,” but general-purpose manipulation is.

A humanoid form factor is attractive because our world is built for human bodies: stairs, door handles, carts, tools. But the economic bar is high. For a humanoid to make sense, it must deliver at least one of these:

- operate where retooling the environment is too expensive

- perform multiple tasks without constant reprogramming

- work safely around people with minimal guarding

Boston Dynamics’ emphasis on generalization in manipulation—both hardware and behavior—reflects the practical truth: a robot that can only do one tightly scripted task is just a machine. A robot that can adapt is a workforce multiplier.

A “People Also Ask” checkpoint

Can robots outperform humans in baseball? Not broadly. Humans still dominate in athletic context, strategy, and adaptability. But robots can outperform humans in narrow physical metrics—repeatable throw speed, consistency, and fatigue resistance.

Why does low impedance matter for collaborative robots? Low impedance helps robots yield during contact, reducing risk and improving handling of impacts and uncertainty—critical for safe human-robot collaboration.

What’s the real takeaway for business leaders? Watch for systems that handle variation and recover from errors. Those are the deployments that scale.

How to evaluate “sports demo tech” for your operation

If you’re responsible for automation, procurement, or innovation, it’s easy to get mesmerized by athletic robotics. Use a simple filter to turn the wow-factor into a business conversation.

The 7 questions I’d ask after any dynamic robotics demo

- What happens on a miss? Does it recover autonomously?

- What’s the intervention rate per hour? (Ask for this number. Don’t accept vibes.)

- How does it handle variability? Lighting, object differences, timing jitter.

- What’s the safety model? Torque limits, collision detection, safe states.

- What sensors are required? And what breaks when a sensor degrades?

- What’s the maintenance profile? Wear parts, calibration needs, downtime.

- What’s the integration path? APIs, PLC compatibility, data logging, retraining loop.

If a vendor (or internal team) can answer these clearly, you’re talking about deployment. If not, you’re watching a demo.

Snippet-worthy reality check: A robot isn’t “autonomous” when it can do the task. It’s autonomous when it can recover from being wrong.

Where this is heading in 2026: faster learning loops, tighter human collaboration

The calendar items in the roundup—online matchups and major conferences like ICRA 2026—hint at what’s next: more cross-pollination between research and operations. The gap is narrowing because simulation, data pipelines, and reinforcement learning are improving, and because companies are now paying for robustness, not just novelty.

Expect three trends to accelerate:

- Multi-skill manipulation: fewer single-purpose cells, more reconfigurable workstations.

- Safer high-speed collaboration: robots working near people without forcing humans to slow down.

- Policy learning with physical constraints: learning systems that bake in impact limits and part protection (like controlled soft falls).

If you care about manufacturing output, warehouse throughput, or healthcare resilience, sports robotics is worth watching—not because you need robots to play baseball, but because baseball exposes the exact capabilities that make automation finally useful in the messy middle.

Robots throwing 70 mph is a headline. The operational question is better: Where in your workflow does speed collide with uncertainty—and what would it be worth to handle that reliably?