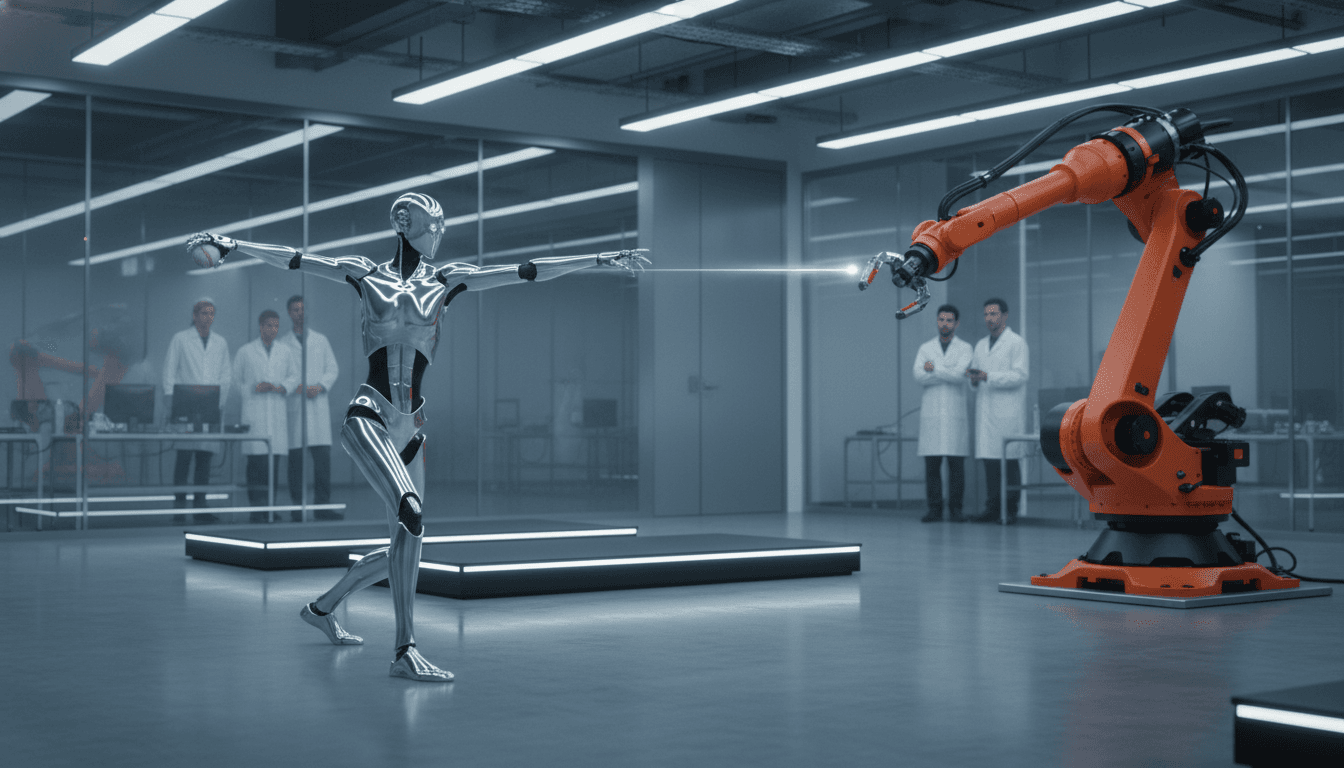

Robots throwing 70 mph highlight dynamic manipulation—the same AI robotics capability driving safer, faster automation in manufacturing and logistics.

Robots Playing Baseball: What It Means for Industry

A robot throwing a baseball at 70 mph isn’t a party trick. It’s a loud, measurable signal that AI-powered robotics is getting good at something industry has struggled with for decades: dynamic manipulation—moving fast, adapting in real time, and handling uncertainty without breaking itself (or your equipment).

That’s why the latest “robots playing catch and batting practice” demos—like the work shown by the RAI Institute—matter well beyond sports. If a robot can track a moving ball, decide where to put its hand, absorb impact, and recover in a split second, it’s a short step to bin picking that doesn’t jam, packaging lines that don’t stop, and fulfillment robots that can handle the weird stuff (soft bags, deformable packages, shifting loads).

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and I’m going to take a stance: baseball-style robotics is one of the clearest windows into what’s coming for manufacturing, logistics, and even emergency response—because it forces robots to operate under the same messy physics that factories deal with every day.

Dynamic manipulation is the real milestone (not the baseball)

Dynamic manipulation means controlling motion and force when the world is changing quickly. In baseball, the ball’s speed, spin, bounce, and timing are constantly shifting. In a warehouse, it’s the same story—just less glamorous: a box slips, a tote flexes, a conveyor jitters, a human steps closer than expected.

What makes the RAI Institute demo notable is the emphasis on a low-impedance platform. In plain terms, low impedance means the robot isn’t trying to be a rigid statue. It’s designed to be compliant—to “give” a little—so it can handle contact, absorb shocks, and stay stable.

Here’s the industry translation:

- Rigid robots are great when everything is fixtured, timed, and predictable.

- Compliant robots are great when the environment is semi-structured and humans or moving objects are involved.

Baseball forces compliance. Catching a ball at 41 mph from 23 feet (7 m) isn’t about raw strength; it’s about sensing contact and modulating force fast enough to avoid rebounds, drops, or joint damage.

Why low impedance shows up in factories

Most companies get hung up on payload and reach. Those specs matter, but they’re not what keeps lines running. The killers are contact events:

- A gripper bumps a bin wall and misaligns the pick

- A part is slightly out of tolerance

- A box collapses under suction

- A robot “wins” a fight against a fixture… and the fixture loses

Low-impedance control and fast feedback loops reduce the cost of these moments because the robot doesn’t respond like a battering ram.

The speed numbers are the headline—and also the warning

The demo claims robots can throw 70 mph (112 kph), catch balls thrown up to 41 mph (66 kph), and hit pitches up to 30 mph (48 kph) at short range. Those numbers are impressive because they imply three hard capabilities working together:

- Perception at speed (vision + state estimation)

- Real-time planning (where should the hand/bat be next?)

- High-bandwidth control (execute motion precisely under changing forces)

But speed also exposes the practical constraints companies should care about:

- Safety: A 70 mph throw is a reminder that dynamic robots need serious safety engineering—sensing, zoning, interlocks, and thoughtful HRI (human-robot interaction) design.

- Wear and maintenance: Faster movement increases stress on gearboxes, belts, bearings, and end effectors.

- Variability tolerance: The win isn’t “fast once.” The win is “fast, repeatable, and robust across shifts.”

A useful way to judge any robotics demo: ask whether the system can handle the 10th percentile case (worst lighting, odd objects, drifted calibration), not the 90th percentile.

What baseball teaches about industrial latency

At 23 feet, a 41 mph ball reaches the catcher in roughly 0.38 seconds. That’s a brutal latency budget. Even if the robot uses prediction, it still needs:

- low-latency sensing (camera exposure + compute)

- fast control cycles

- minimal mechanical backlash

In factories, latency budgets are usually larger—but the same dynamics show up when:

- picking from a moving conveyor

- tracking parcels on a sorter

- doing high-speed placement in packaging

This is why sports robotics is a decent proxy: it forces the stack (hardware + software) to behave like a real product, not a slow lab demo.

Human-robot collaboration isn’t a slogan—it’s trained behavior

One of the most interesting parts of these sports demos is robots working with skilled humans, not in a fenced-off cell. That matters because collaborative robots (cobots) are moving from “safe but slow” to “safe enough and productive.”

You can see this shift echoed in industry conversations too—like the discussion featuring Brad Porter and Alfred Lin on where robotics, AI, and automation are headed. The direction is clear: customers want robots that can share space, share tasks, and share responsibility.

Collaboration needs predictability more than raw intelligence

In practice, humans don’t need robots to be “smart.” They need robots to be legible:

- The robot’s intent should be obvious

- Motions should be consistent

- Recoveries from errors should be calm, not chaotic

A robot catching a ball near a person must manage micro-contacts and timing in a way that feels predictable. That’s the same requirement for:

- kitting stations

- assembly assist

- palletizing next to workers

If you’re evaluating AI robotics vendors, ask how they handle:

- near-misses and incidental contact

- speed reduction zones

- re-planning when a human reaches in

Beyond baseball: the week’s robotics themes that matter for business

The RSS roundup points to a broader pattern: the industry isn’t betting on one trick. It’s building a toolkit—dynamic manipulation, robust mobility, safer learning, and mission-specific autonomy.

1) Bigger reach + mobility: GIRAF and field-ready manipulation

The “GIRAF” system (Greatly Increased Reach AnyMAL Function) highlights a practical truth: reach is productivity. A capable arm on a mobile base can service more workpoints, reduce fixed infrastructure, and adapt to site layouts.

Where this pays off first:

- industrial inspection (valves, gauges, thermal scans)

- maintenance tasks in mixed indoor/outdoor sites

- inventory checks in large facilities

The lesson from baseball carries over: contact-rich tasks demand compliance and fast control. A long-reach arm makes that harder, not easier—so advances here are meaningful.

2) Safer learning: “controlled, soft falls” and protecting assets

One research item in the roundup proposes a reward function for reinforcement learning that balances achieving an end pose with minimizing impact and protecting critical parts. That’s not academic nitpicking. It’s a direct response to a blocker in real deployments:

- Training robots in the real world is expensive when failures break hardware.

If we want more capable bipedal or humanoid robots (or even just faster arms), we need learning systems that treat hardware preservation as a first-class objective.

Industry translation:

- fewer catastrophic crashes during commissioning

- faster iteration on new SKUs and tasks

- higher uptime and lower spares inventory

3) Emergency response autonomy: DARPA Triage Challenge

DARPA’s Triage Challenge is about medical triage in mass casualty incidents where resources are limited. The relevance to AI robotics in industry is the decision-making structure:

- incomplete information

- time pressure

- prioritization under constraints

Those same patterns show up in:

- smart city incident response (traffic control, situational awareness)

- industrial safety monitoring

- disaster logistics and supply distribution

A robot that can decide “what matters most next” is more valuable than a robot that can only execute a fixed script.

How to apply these lessons to manufacturing and logistics in 2026

If you’re leading operations, engineering, or innovation, the question isn’t “Should we build a baseball robot?” It’s: Which dynamic manipulation capabilities map to our bottlenecks?

Here’s a practical way to think about it.

Start with tasks that have motion + contact + variability

Dynamic manipulation shines when all three show up:

- Motion: parts on conveyors, moving bins, sorter exits

- Contact: insertion, snapping, pushing, seating, closing

- Variability: mixed SKUs, deformables, inconsistent poses

Examples that are often good candidates:

- high-mix case packing where boxes deform

- depalletizing with crushed cartons

- unloading trailers where stacks shift

- assembly steps with tight tolerances and occasional misalignment

Use sports-style metrics when you evaluate vendors

Baseball gives you measurable metrics—speed, reaction time, success rate. Bring that mindset into vendor evaluation:

- Cycle time at required success rate (e.g., 99.5% at 6 seconds)

- Recovery behavior (what happens after a miss?)

- Contact handling (does it detect and yield, or fight?)

- Changeover time (new SKU, new bin, new lighting)

- Mean time to intervention (how often a human must step in)

If a vendor only shows “happy path” demos, you’re buying a prototype.

Don’t ignore the boring parts: integration and maintainability

I’ve found that most ROI models fail because they underprice integration and overprice autonomy. The winners focus on:

- simple end effectors with robust sensing

- clear maintenance plans (spares, lubrication, calibration)

- monitoring dashboards that operations teams actually use

Dynamic manipulation is great—but the business value shows up when it runs for months, not minutes.

What to watch next (and what I’m skeptical about)

Two trends are converging:

- Humanoids and high-DOF systems are showing more acrobatics and agility.

- Industrial buyers still care about uptime, safety, and total cost per pick.

My take: we’re going to see a split.

- In logistics and manufacturing, the first big wins will come from task-specific systems that borrow dynamic manipulation techniques (fast perception, compliant control) without insisting on a humanoid form.

- Humanoids will find early traction in infrastructure-light environments—where the cost of retooling the world exceeds the cost of a more general robot.

And yes, the dance videos will get weirder. Once mocap choreography runs out, companies will show off motions that humans can’t do comfortably—because it’s a clean way to demonstrate control authority and stability margins.

Where this leaves your business

Robots throwing and catching baseballs are fun to watch. The serious part is what’s underneath: fast perception, compliant control, and robust decision-making under uncertainty. Those are the same ingredients behind practical AI automation in warehouses, factories, healthcare response, and smart infrastructure.

If you’re planning 2026 initiatives, pick one line or cell where variability is killing throughput and pilot a system that’s explicitly designed for contact and recovery—not just perfect picks in perfect lighting. That’s where the ROI hides.

The next time you see a sports robotics demo, don’t ask, “Can it play?” Ask: What’s its error recovery story, and how much does a mistake cost? The companies that can answer those two questions are the ones that will turn robotics videos into operational advantage.