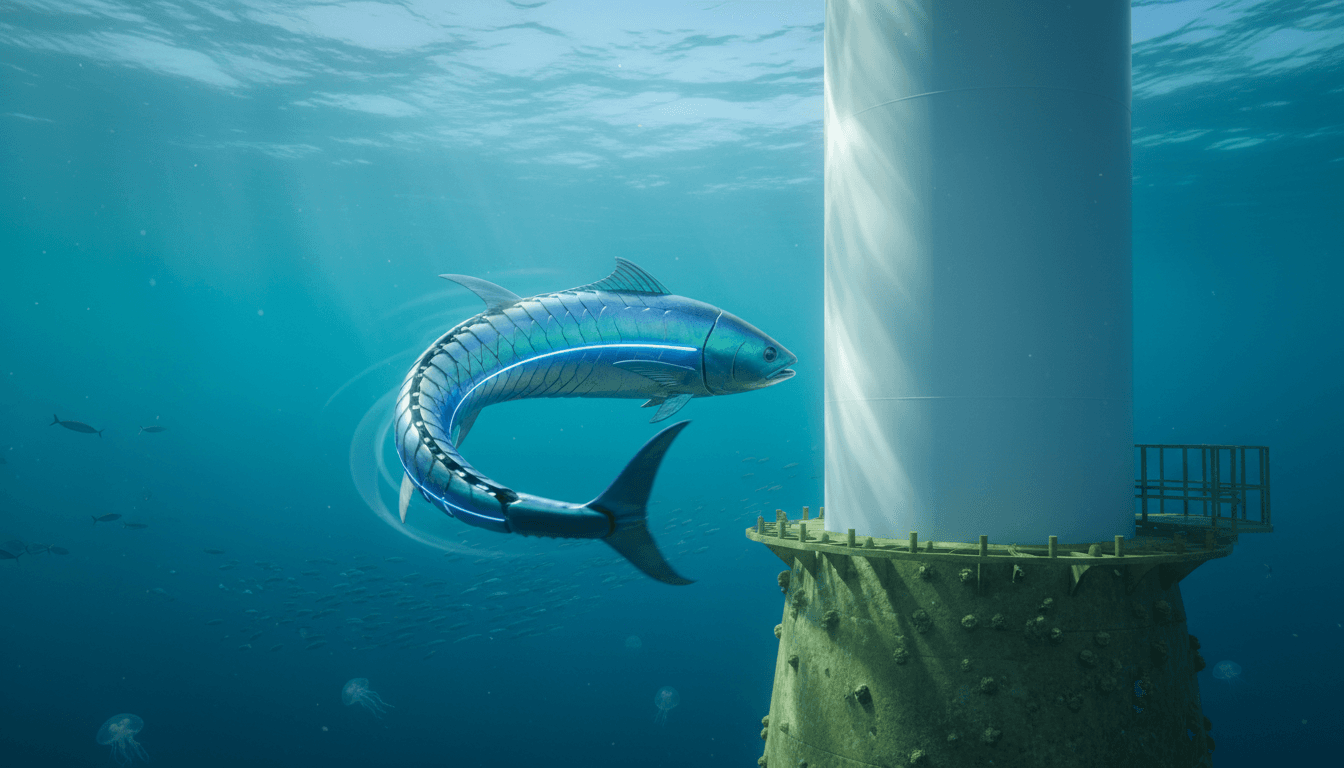

Flexible electromagnetic fins help robotic fish swim fast and turn tight—ideal for AI-driven underwater inspection and ecological monitoring.

Robotic Fish Fin Design: Fast Turns, Real-World Work

A robotic fish that can hit 1.66 body lengths per second and carve a turn within a 0.86 body-length radius isn’t a cute lab demo. It’s a signal that underwater robotics is starting to get the one thing industry actually needs: controlled agility in tight, fragile, and expensive environments.

That matters because underwater work has a nasty combination of constraints: visibility is poor, GPS doesn’t work, currents don’t cooperate, and sending humans down is slow, risky, and costly. Most underwater robots today either look like mini-submarines with propellers (great endurance, mediocre maneuverability) or soft-bodied concepts that move beautifully but struggle to produce useful thrust. The newest robotic fish fin research—built around a flexible electromagnetic fin—tries to thread that needle: compact, powerful, and compliant, closer to muscle than a rigid motor linkage.

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and I’m going to take a stance: the real breakthrough isn’t “a fish robot that swims fast.” It’s the combination of predictable actuation + soft mechanics, which is exactly what you need before AI can reliably control fleets of agile robots in the ocean.

Why most underwater robots still feel clumsy

Underwater robots typically win on one axis and lose on another.

Propeller-driven ROVs/AUVs are dependable workhorses for inspection and mapping, but they’re not great at threading through clutter, hovering near delicate surfaces, or making fast, tight evasive moves when conditions change. They also produce turbulence that can disturb sediment, reduce visibility, and stress wildlife.

Soft robotics promises fish-like motion and safer contact, but it often runs into two practical problems:

- Low force output: flexible actuators can be too weak to push a payload or fight currents.

- Hard-to-model behavior: if the actuator’s output is unpredictable, control becomes trial-and-error.

Here’s the thing about industrial underwater tasks—pipeline checks, seawall surveys, offshore wind inspections, aquaculture monitoring—you can’t “kind of” control the robot. If it drifts into a barnacle-covered cable or bumps coral, the mission becomes a liability.

That’s why this research direction is interesting: it’s trying to deliver real thrust in a flexible form factor, while also building a model that maps electrical input to hydrodynamic output.

The flexible electromagnetic fin: muscle-like power without bulky motors

The research team, led by Fanghao Zhou at Zhejiang University, built a fin that uses two small coils and spherical magnets. Feed the coils alternating current, and you generate an oscillating magnetic field that makes the fin flap back and forth—tail-like propulsion without a rigid motor assembly.

What’s different about this approach

Most “fast” robot fins rely on motors and linkages. They can generate strong thrust, but they’re often bulky, rigid, and mechanically complex—exactly what you don’t want when you’re trying to miniaturize.

This design adds an elastic joint that helps the fin swish with low friction and return to a neutral rest position when not excited. In practical terms, that suggests:

- Mechanical compliance (safer near fragile environments)

- Compact packaging (good for small platforms)

- Simpler sealing compared with complex gear trains (a constant underwater headache)

The numbers that make it worth paying attention to

In pool tests, the fin generated:

- Speed: 405 mm/s, or 1.66 body lengths per second

- Turning radius: about 0.86 body lengths

- Peak thrust: 0.493 N

- Fin mass: 17 g

For readers used to big ROV specs, 0.493 N might sound small. But in the context of a lightweight, biomimetic swimmer, it’s a meaningful thrust-to-weight signal—especially when paired with tight turning.

If you’re building an autonomous platform that needs to inspect complex structures (think: the lattice beneath an offshore platform or the tight geometry around an intake), turning radius often matters more than raw top speed.

Predictable thrust is what enables AI control underwater

Zhe Wang, a Ph.D. student on the project, highlighted a key point: the team built a mathematical model connecting electrical input to hydrodynamic thrust output.

That sentence should jump out if you care about real deployments.

Soft robotics has a reputation for being hard to control because the body deforms, interacts with fluids, and responds nonlinearly. A model that lets you predict behavior from input current is a step toward engineering-grade repeatability.

Where AI fits (and why it’s not optional)

For an agile robotic fish to do more than swim in a pool, it needs autonomy that can handle uncertainty:

- currents that change minute-to-minute

- biofouling and wear that alter performance

- tight spaces where a small error becomes a collision

A practical control stack for robotic fish propulsion often becomes a hybrid:

- Physics-based model (fast, interpretable baseline control)

- Learning-based adaptation (compensates for unmodeled dynamics and drift)

- High-level autonomy (path planning, obstacle avoidance, mission logic)

The model they’re building acts like the foundation for #1. Once you have that, machine learning has something stable to refine instead of guessing from scratch.

Snippet-worthy reality: If you can’t predict thrust from input, you can’t promise safety, endurance, or repeatable inspection coverage.

Energy efficiency: the barrier between “cool” and “useful”

The researchers were blunt: the electromagnetic coils draw a lot of current, shortening swim duration.

That’s not a minor footnote. It’s the difference between a system that can scout for 8 minutes and one that can patrol for 8 hours.

Why electromagnetic actuation tends to be power-hungry

Electromagnetic systems can deliver responsive motion, but they often burn power as heat in the coils (resistive losses). Underwater, you also have packaging constraints: you can’t always scale coil size, cooling, and battery capacity the way you might on land.

The most promising efficiency fixes (and what I’d watch in 2026)

The team mentioned three directions: coil geometry optimization, energy recovery circuits, and smart control strategies. Those map nicely to a practical roadmap:

- Better electromagnet design: reduce resistive loss, improve magnetic coupling, tune resonance

- Energy recovery: capture energy during oscillation deceleration (think regenerative braking, but for fins)

- Control that pulses instead of blasts: excite only when needed, exploit mechanical elasticity, avoid constant drive

If you’re evaluating underwater robotics for industrial use, ask vendors (or your internal team) a simple question: “What’s your energy per meter traveled in representative conditions?” Top speed is marketing; energy-per-distance is operations.

Where robotic fish actually fit in industry (and where they don’t)

Robotic fish aren’t going to replace heavy ROVs that carry tools, cutters, and manipulators. But they can win in niches where stealth, safety, and agility beat brute force.

High-value use cases in the next 12–24 months

Here are applications where a flexible electromagnetic fin plus AI control is a credible fit:

- Ecological monitoring: swimming near reefs or sea grass with minimal disturbance; quieter propulsion helps

- Underwater infrastructure inspection (lightweight): early-stage anomaly spotting around cables, pylons, and intake structures

- Aquaculture monitoring: fish behavior observation, net integrity checks, localized environmental sensing

- Confined-space surveying: tanks, culverts, and complex structures where propellers are risky

A practical pattern I’ve seen work: use agile robotic swimmers as scouts that flag issues, then send a tool-carrying ROV only when needed. That’s how you reduce vessel time and inspection cost without betting everything on one platform.

Where you should be skeptical

Robotic fish will struggle (for now) when missions require:

- long-range transit against strong currents

- heavy payloads (sonars, manipulators, thick housings)

- extended endurance without frequent recharge or retrieval

The energy draw mentioned in the study is the giveaway: the platform is trending toward agility-first, not endurance-first.

Multi-fin coordination is the real scaling story

The team expects the fin system to scale into multi-fin configurations and plans to study coordinated motion.

That’s where underwater robotics starts to look like a serious industrial platform rather than a single-actuator experiment.

Why multi-fin matters

With multiple fins, you can separate control objectives:

- stability/hovering (fine control)

- burst acceleration (short, high-thrust maneuvers)

- precise turning (yaw control without wasting forward thrust)

From an AI standpoint, multi-fin systems also create richer control inputs. That’s good because it enables strategies like:

- adaptive gait selection (different fin patterns for cruise vs. maneuver)

- fault tolerance (degrade gracefully if one fin underperforms)

- energy-aware planning (choose the cheapest motion that meets the task)

If you’re tracking AI-powered robotics trends, this is a familiar arc: more actuators and more sensing lead to better autonomy—but only if the system stays modelable and power-efficient.

Practical questions teams should ask before piloting robotic fish

If you’re in marine operations, utilities, offshore energy, ports, or environmental services, these questions will keep a pilot grounded:

- What’s the endurance at mission speed? Ask for minutes at realistic currents, not pool conditions.

- How is thrust modeled and validated? Look for sensor-backed models, not “it swims well.”

- What’s the failure mode near assets? If control drops, does it float, stop, or keep thrashing?

- How do you localize underwater? Visual-inertial, acoustic beacons, Doppler velocity logs—pick what fits your site.

- What’s the data product? Inspection is about deliverables: defect tags, maps, and repeatable coverage.

This is where AI and robotics transformation becomes real: not a prototype swimming fast, but a system that produces repeatable operational outputs.

What this signals for AI + robotics in 2026

A flexible electromagnetic fin with measurable thrust, high agility, and an input-to-output model is a strong step toward deployable biomimetic underwater robots. The research still has a clear bottleneck—energy consumption—but the engineering direction is sensible and solvable.

For the broader “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” story, this is the pattern to watch: hardware that’s compliant and compact, paired with models and AI control that make behavior predictable. That combination is how robotics moves from impressive motion to trusted automation.

If you’re considering underwater automation—inspection, ecological monitoring, or scouting around sensitive assets—start building your evaluation criteria now. When multi-fin coordination and smarter power electronics mature, robotic fish won’t just be interesting. They’ll be part of the toolkit.

What would you automate first if you had a quiet, agile underwater robot that could safely operate close to structures and marine life?