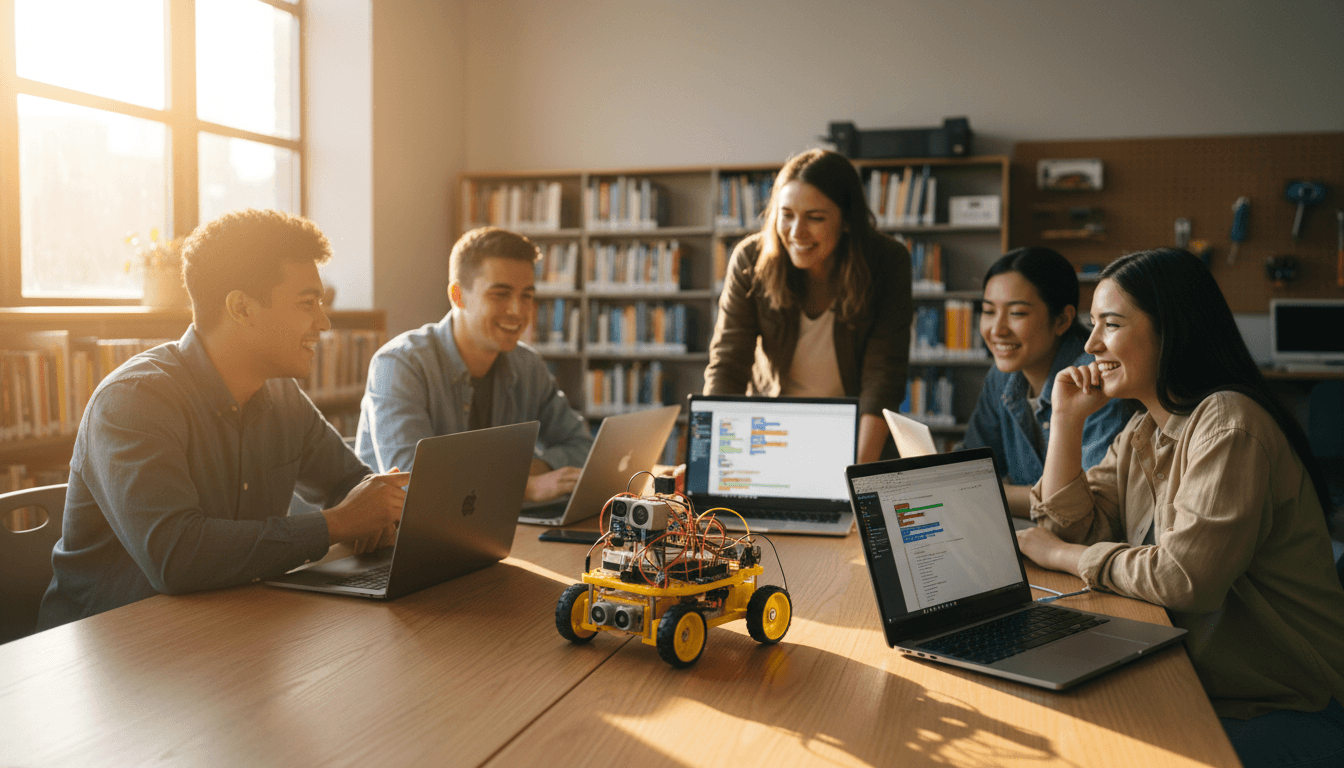

Open-source, low-cost robots are widening access to robotics education—building a stronger, more inclusive AI workforce. See what to copy in 2026.

Open-Source Robots Are Making STEM Truly Accessible

Robotics education has had a quiet, expensive problem for decades: students are told to “learn robotics,” but the actual robots are locked behind budgets, lab rules, and fear of breaking something that costs more than a semester’s tuition. Carlotta Berry—now a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology—ran into that wall as an undergrad in the 1980s and ’90s. She studied robots but wasn’t allowed to touch them because they were “too expensive.”

That frustration became a blueprint. Berry’s work on open-source, low-cost, modular, 3D-printed robots (including her early modular design, the LilyBot) is a practical answer to a question that matters far beyond classrooms: How do we build an AI and robotics workforce if only a small slice of people ever get hands-on time with the machines?

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and I’m taking a clear stance: inclusive robotics education isn’t a feel-good side project. It’s infrastructure for the next decade of automation, human-robot collaboration, and AI-enabled operations.

Open-source robotics is a workforce strategy, not a hobby

Answer first: Open-source, low-cost educational robots reduce the two biggest barriers to robotics skills—price and access—making them one of the fastest ways to expand the future AI and robotics talent pipeline.

Most industry leaders talk about skills gaps as if they’re mysterious. They aren’t. If a student can’t physically build a robot, wire sensors, troubleshoot power issues, and iterate on code, they don’t develop the instincts employers pay for. Berry’s original undergrad experience—learning robotics without being allowed to interact with robots—still happens in subtler forms: limited lab availability, shared kits, outdated hardware, or “watch the demo” teaching.

Open-source hardware flips the model:

- Lower cost per learner means more kits in more hands.

- Repairability and replaceable parts means less fear of failure (failure is the curriculum).

- Community iteration means designs improve publicly instead of behind vendor roadmaps.

- Local fabrication (3D printing) means schools and libraries can maintain systems without expensive service contracts.

From an industry lens, this is how you get more people capable of working on real robotics systems—mobile robots, industrial automation, service robots, and the AI software that increasingly drives them.

Why hands-on robotics matters more in the AI era

AI in robotics isn’t just “smart code.” It’s code living inside constraints: sensor noise, motor backlash, battery sag, lighting variation, wheel slip, and fragile connectors. The gap between a simulation and a working robot is where many new hires struggle.

A good educational robot forces learners to practice the real sequence every robotics team uses:

- Sense: Use sonar, microphones, cameras, IMUs—then handle imperfect data.

- Plan: Decide what to do next—rules, classical control, or AI-based policies.

- Act: Move—motors, servos, safety limits, and timing.

Berry’s outreach approach makes that “sense–plan–act” loop tangible for kids and educators, not just engineering majors.

Representation and access: the missing layer in most STEM plans

Answer first: Diversity in STEM doesn’t improve because organizations publish statements; it improves when learners can see themselves in the field and can access the tools early enough to build confidence.

Berry’s story includes a second kind of exclusion—being one of only a few students who were female or Black in her engineering program. She’s blunt about how isolating that can feel, and she’s right that representation does matter.

The stats she cites are the kind that should make any robotics leader uncomfortable: about 8% of electronics engineers are women and about 5% are Black. Those numbers aren’t just about fairness; they’re also a signal that we’re leaving massive talent on the table.

Here’s the reality I’ve seen across technical teams: if your early pipeline is narrow, your hiring options stay narrow, and your product decisions become narrow too. Human-robot interaction, especially, benefits from diverse perspectives because robots operate in human spaces, around human bodies, under human social expectations.

What inclusive robotics education looks like in practice

Berry’s model is surprisingly straightforward: go where people are.

Instead of requiring students to come to a campus lab, she brings robots to:

- schools

- libraries

- museums

- community events

- global virtual workshops (with mailed parts)

At Indianapolis Public Library branches, for example, children roughly ages 3 to 10 learned robotics concepts through concrete interactions—how sensors “see,” how microphones and speakers enable “hearing” and “talking,” and then they got to play with the robots. That last part isn’t fluff. Play is debugging for beginners.

The LilyBot lesson: modular, 3D-printed robots scale learning

Answer first: Modular, 3D-printed open-source robots scale because they’re easy to assemble, easy to modify, and forgiving when parts fail—ideal conditions for teaching robotics and human-robot interaction.

While the RSS summary doesn’t list a full bill of materials, the design principles described—open-source, modular, low-cost, 3D-printed—are exactly what educational robotics should prioritize. Modular systems let a beginner start with a wheeled base and one sensor, then add capabilities over time:

- Add sonar for obstacle avoidance

- Add audio I/O for interaction demos

- Add camera modules for basic computer vision

- Add better motor drivers for more precise control

- Swap chassis parts to test stability, payload, and wheel geometry

That modularity also maps nicely to how AI and robotics are used in industry. Real deployments rarely start “fully autonomous.” They start with a constrained workflow and expand as reliability improves.

Human-robot interaction belongs in early curricula

Berry teaches human-robot interactions alongside mobile robotics. That’s a smart choice, and more programs should copy it.

Industry needs engineers who can answer questions like:

- How does a robot communicate intent—lights, sound, motion cues?

- How do we set boundaries and safety behaviors around people?

- What happens when a user doesn’t trust the robot, or over-trusts it?

- How do we design for accessibility (height, sound, language, mobility)?

Those are not “soft” questions. They determine adoption, safety outcomes, and ROI.

“Taking robots to the streets” is how you build adoption at scale

Answer first: Community-based robotics outreach is a practical way to grow skills quickly because it reaches learners and educators who don’t have institutional access.

Berry’s phrase—“to the streets”—captures a key idea: the most scalable STEM programs don’t wait for perfect lab conditions. They build confidence first, then deepen skills.

A standout example from the RSS summary is the global workshop model: grad students in places like Costa Rica, Niger, and Uganda received robot parts by mail, then learned to build and program them with Berry’s guidance.

For organizations focused on AI and robotics adoption worldwide, that model is instructive. It shows how to:

- decouple learning from expensive infrastructure

- ship standardized kits

- teach remotely with shared open-source documentation

- create local mentors who can teach the next cohort

If you’re designing a program, copy these three mechanics

If you’re a school district, nonprofit, corporate foundation, or training leader trying to grow robotics capability, these are the tactics that tend to work:

-

Make the first win happen in 30 minutes

A robot that moves, beeps, or avoids an obstacle quickly keeps people engaged. -

Teach with failure on purpose

Loose wires, mis-calibrated sensors, wrong motor polarity—these are learning moments, not disasters. -

Train the trainers, not just the students

When educators can maintain and modify kits, programs survive beyond one champion.

Online communities turn mentorship into a multiplier

Answer first: Professional communities reduce isolation, increase retention, and create mentorship at a scale universities can’t match alone.

Berry cofounded Black in Engineering and Black in Robotics in 2020 as part of the broader Black in X network (more than 80 organizations). The timing makes sense: the pandemic pushed professional networking online, and people who felt isolated found each other.

From a workforce development standpoint, communities do three valuable things:

- Retention: People stay in the field when they can compare notes and get unblocked.

- Visibility: Students can see real careers, not just abstract majors.

- Opportunity flow: Jobs, speaking invitations, research collaborations, and project ideas circulate faster.

Berry also received the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society Undergraduate Teaching Award in 2023, which signals something many universities overlook: high-impact teaching and outreach can be technical leadership, not a distraction from it.

What business and education leaders should do in 2026

Answer first: To build the AI and robotics workforce, invest in open-source educational robots, hands-on curricula, and community partnerships—then measure outcomes like kit utilization and learner progression.

If you lead a robotics team or fund STEM programs, here’s a practical, measurable playbook:

- Adopt open-source robotics kits for introductory learning so costs don’t cap participation.

- Standardize a “sense–plan–act” curriculum that maps to real robotics jobs.

- Partner with libraries and community centers (they’re already trusted distribution points).

- Budget for parts replacement (consumables are normal; scarcity kills experimentation).

- Create clear pathways from “first robot demo” → “student project” → “internship-ready portfolio.”

And don’t miss the point Berry keeps emphasizing: visibility matters. If your program’s mentors all look the same, learners draw conclusions—often subconsciously—about who belongs.

“Inclusive robotics education is the cheapest way to expand the automation workforce.”

I believe that sentence is going to age well.

Where this fits in the bigger AI & robotics industry shift

The broader theme of this series is how AI-powered robotics is changing manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, retail, and cities. Those deployments require more than algorithms; they require technicians, engineers, operators, and designers who understand how machines behave in messy environments.

Open-source, low-cost robots like Berry’s approach do something industry needs urgently: they turn more people into builders. If you’re trying to hire for robotics roles in 2026, you’re competing with everyone else. Expanding the pipeline is not charity—it’s planning.

The next question is simple: If learners in your community had a robot on the table next week, who would show up to build it?