Marine heat waves are weakening ocean carbon storage. Autonomous profiling robots and AI analytics reveal why—and what climate and industry leaders should do next.

Ocean Carbon Storage Is Faltering—Robots Prove It

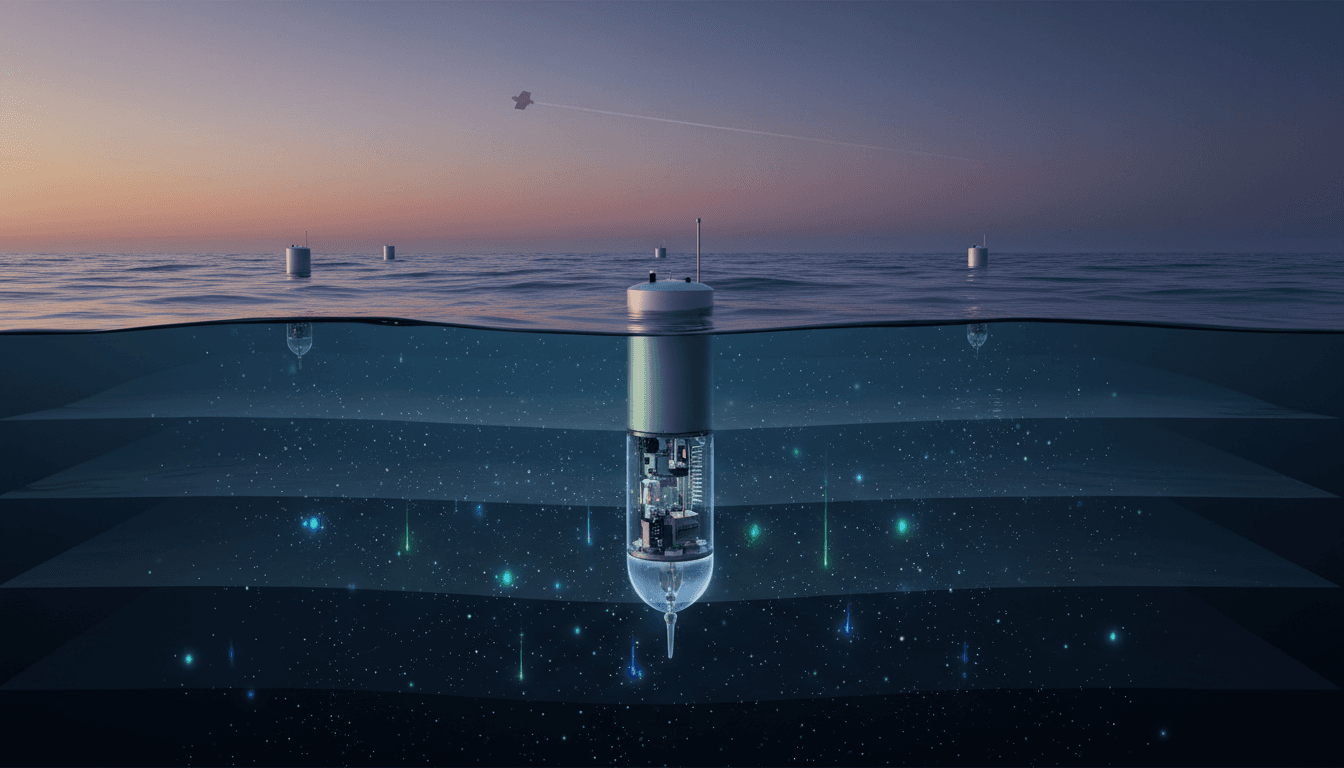

A single marine heat wave can rewire an ocean ecosystem for years. What’s new is that we can now measure the downstream damage to carbon storage—continuously, at scale, and far below the surface—because thousands of autonomous ocean robots are quietly doing the work humans can’t.

The latest signal comes from a fleet of free-floating biogeochemical robots that profile the ocean’s “vital signs.” Research published in Nature Communications shows that marine heat waves are interfering with the ocean’s ability to move carbon from surface waters into the deep ocean, where it can stay locked away for centuries. That’s a big deal for climate risk, for any business exposed to climate-driven regulation or supply chain volatility, and for anyone betting on carbon markets to mature into something reliable.

This post sits squarely in our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series for a reason: these profiling floats are one of the clearest examples of robotics changing an entire industry workflow—from episodic ship expeditions to near–real time, always-on environmental intelligence.

The ocean’s carbon “elevator” is slowing—heat waves are a key reason

The core finding is straightforward: marine heat waves can reduce the depth and effectiveness of carbon export into the deep ocean. When the biology changes near the surface, the carbon pathway changes all the way down.

Here’s the mechanism, simplified without losing the plot. A big chunk of ocean carbon storage depends on tiny life:

- Plankton grow in sunlit surface waters, pulling CO2 into biomass.

- That biomass becomes sinking organic material (particles, aggregates, fecal pellets).

- As it sinks, bacteria “eat” it. If breakdown happens shallow, carbon returns to the atmosphere quickly. If it sinks deep—think kilometers, not tens of meters—it can be isolated from the atmosphere for hundreds of years.

Heat waves don’t just warm water. They can shift plankton species, timing, and food-web structure, changing the size, density, and sink-rate of particles. Smaller or more easily degraded particles tend to get “remineralized” (converted back to CO2) earlier in the descent.

A line that sticks with me: the ocean’s services aren’t guaranteed. We talk about the ocean as if it’s an infinite sponge for heat and carbon. The data says it’s more like a living system with thresholds.

Why underwater robots are now essential to climate monitoring

The deeper story isn’t only about carbon—it’s about how we know. Satellite monitoring mostly stops at the surface. Ships provide precision, but they’re intermittent and expensive. The ocean’s carbon cycle runs 24/7 across seasons, storms, and remote regions. That mismatch used to force scientists to infer what they couldn’t observe.

Autonomous biogeochemical (BGC) profiling floats changed the cadence of ocean science:

- They drift and profile repeatedly, typically over ~250 dive cycles across up to seven years.

- They collect measurements through the water column (often down to 1,000–2,000 meters).

- They surface briefly to send data via satellite (Iridium), then disappear again.

- Data is publicly shared rapidly under international agreements.

This is what “industry transformation” looks like in environmental science: a shift from campaigns to continuous operations. You don’t “go measure” the ocean anymore; you operate measurement.

What these floats measure (and why it matters)

These aren’t just temperature probes. The GO-BGC Array floats (U.S.-led, coordinated by MBARI and partners) include sensors that track the ocean’s metabolism:

- Oxygen (a key tracer for biological breakdown of sinking carbon)

- pH (ocean acidity, linked to CO2 uptake)

- Nitrate (nutrient cycling and productivity)

- Suspended particles and chlorophyll (biological activity and particle formation)

- Temperature, conductivity, depth (physical context)

MBARI has deployed 330+ advanced BGC floats as part of this program, alongside the broader international Argo network of 4,000+ floats built over 26 years.

“Robots don’t replace ships”—they make ships smarter

Most companies get this wrong when they think about robotics: they frame it as replacement. In oceanography, it’s closer to stacking capabilities.

- Satellites provide wide coverage and trend detection at the surface.

- Floats provide year-round, depth-resolved context and continuity.

- Ships provide high-precision calibration, samples (like DNA), and targeted investigations.

Put differently: satellites find the headline, floats explain the story, ships validate the details.

What the floats revealed in the Gulf of Alaska (and why you should care)

The study used float data to examine the aftermath of a major North Pacific marine heat wave in the Gulf of Alaska from 2013–2015 (“the Blob”) and a later event in 2019–2020.

To strengthen interpretation, researchers paired float profiles with seasonal ship-based surveys (including plankton pigments and environmental DNA from seawater) from a long-running monitoring effort (Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Line P program).

The key insight: heat waves triggered ecosystem shifts that altered carbon export, meaning less carbon made it into long-term storage depths.

Why a regional result becomes a global risk

It’s tempting to dismiss this as “one region, one story.” That’s not how the climate system works.

- The ocean absorbs about 95% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases. That heat drives more marine heat waves.

- The ocean also absorbs a substantial fraction of human CO2 emissions each year, buffering atmospheric warming.

- If warming reduces carbon export efficiency in multiple key regions, the ocean’s role as a stabilizer weakens.

There’s a business parallel here: if your biggest “sink” for risk starts failing under stress, you don’t wait for perfect certainty. You build better monitoring, models, and contingency plans.

AI turns ocean robots into decision-grade intelligence

Collecting petabytes of profiles is one problem. Converting it into reliable, actionable insight is another. This is where AI in environmental monitoring moves from hype to necessity.

The GO-BGC program is already applying machine learning to extract new biogeochemical signals. For example, an August study in Global Biogeochemical Cycles used a neural network on BGC-Argo float data to show that nitrate production has been rising in the Southern Ocean for more than two decades—a region central to carbon uptake and global nutrient distribution.

Where machine learning helps (and where it doesn’t)

Here’s the reality: ocean data is noisy, sparse in places, and full of confounding variables. AI helps when it’s used for specific jobs:

- Gap-filling and interpolation: Estimating conditions between profiles, times, and locations.

- Pattern detection: Identifying regimes associated with heat waves, productivity shifts, or oxygen anomalies.

- Sensor drift detection: Flagging calibration issues automatically across thousands of instruments.

- Forecasting: Creating early-warning systems for ecosystem shifts tied to heat and carbon export.

But AI doesn’t magically replace physics or chemistry. The best results come from hybrid approaches—machine learning constrained by ocean dynamics and validated against ship samples.

A snippet-worthy way to say it: Robotics makes the measurements possible; AI makes the measurements useful.

What this means for climate tech, carbon markets, and industry strategy

If you work anywhere near sustainability, climate risk, or carbon accounting, the implications are uncomfortable but practical.

1) Carbon sequestration claims need better ocean baselines

Ocean-based carbon ideas—whether direct interventions or crediting mechanisms—depend on proving additionality and durability. If marine heat waves can measurably reduce natural carbon export, then baselines can drift faster than many accounting frameworks assume.

Better baselines require continuous measurement. BGC floats provide the kind of persistent evidence carbon markets will eventually demand.

2) Fisheries and coastal economies get early warning signals

Plankton shifts ripple into fish recruitment, food webs, and ultimately seafood supply. Data streams from profiling floats can support:

- seasonal outlooks for productivity

- detection of low-oxygen risks

- identification of ecosystem regime shifts after heat waves

This isn’t a nice-to-have for coastal planning—it’s operational intelligence.

3) Climate adaptation needs “subsurface observability”

Most climate dashboards overweight surface indicators because that’s what’s easily observed. The carbon cycle and many ecosystem stress signals happen at depth. Building adaptation strategies without subsurface data is like running a factory with only a front-door camera.

The big bottleneck: funding and continuity

The GO-BGC effort has been supported by a US $53 million National Science Foundation grant (awarded in 2020). That grant expires this year, and continuation funding hasn’t been secured.

This is the part that should bother everyone who says they want “data-driven climate decisions.” These floats are not a one-off research gadget. They’re infrastructure.

Also, the fleet isn’t immortal:

- Each float lasts up to ~7 years.

- The program loses roughly ~5% per year to corrosion, connection problems, ship strikes, or bottom entrapment.

If replacement and expansion stall, the data record fragments right when marine heat waves are becoming more frequent and severe.

Practical takeaways: how to use this robotics + AI story in your organization

If you’re reading this because you care about AI and robotics transforming industries, treat the ocean-float model as a blueprint.

A simple template worth copying

- Instrument the hard-to-observe environment with autonomous robotics (not just sensors—systems that operate).

- Transmit data quickly into shared pipelines (near–real time beats perfect-but-late).

- Use AI for triage and interpretation, not as a substitute for measurement.

- Keep humans in the loop for calibration, audits, and targeted deep dives.

Questions to ask your team this quarter

- Where are we still relying on episodic measurement when we actually need continuous monitoring?

- What would our “profiling float” equivalent look like—autonomous, persistent, and scalable?

- Are we investing more in dashboards than in the data supply chain that makes dashboards trustworthy?

“The reality? It’s simpler than you think: you can’t manage what you can’t observe—especially under stress.”

Where this goes next

Underwater robots are showing that ocean carbon storage is struggling during marine heat waves—not in theory, but in measured changes to biology and carbon export pathways. That evidence matters because it tightens the link between climate extremes and the planet’s ability to buffer our emissions.

For the AI and robotics industry, this is also a clear signal: environmental monitoring is becoming a serious robotics market, with demanding requirements—battery life, reliability, calibration, communications, autonomy, and analytics at scale.

The open question isn’t whether we can measure the ocean’s vital signs. We already can. The question is whether we’ll treat that capability as a research extra—or as critical infrastructure we maintain before the next “Blob” arrives.