High-speed drone landings at 110 km/h and AI-to-ROS tools signal a shift: robots are becoming deployable, not just impressive. See what it means for industry.

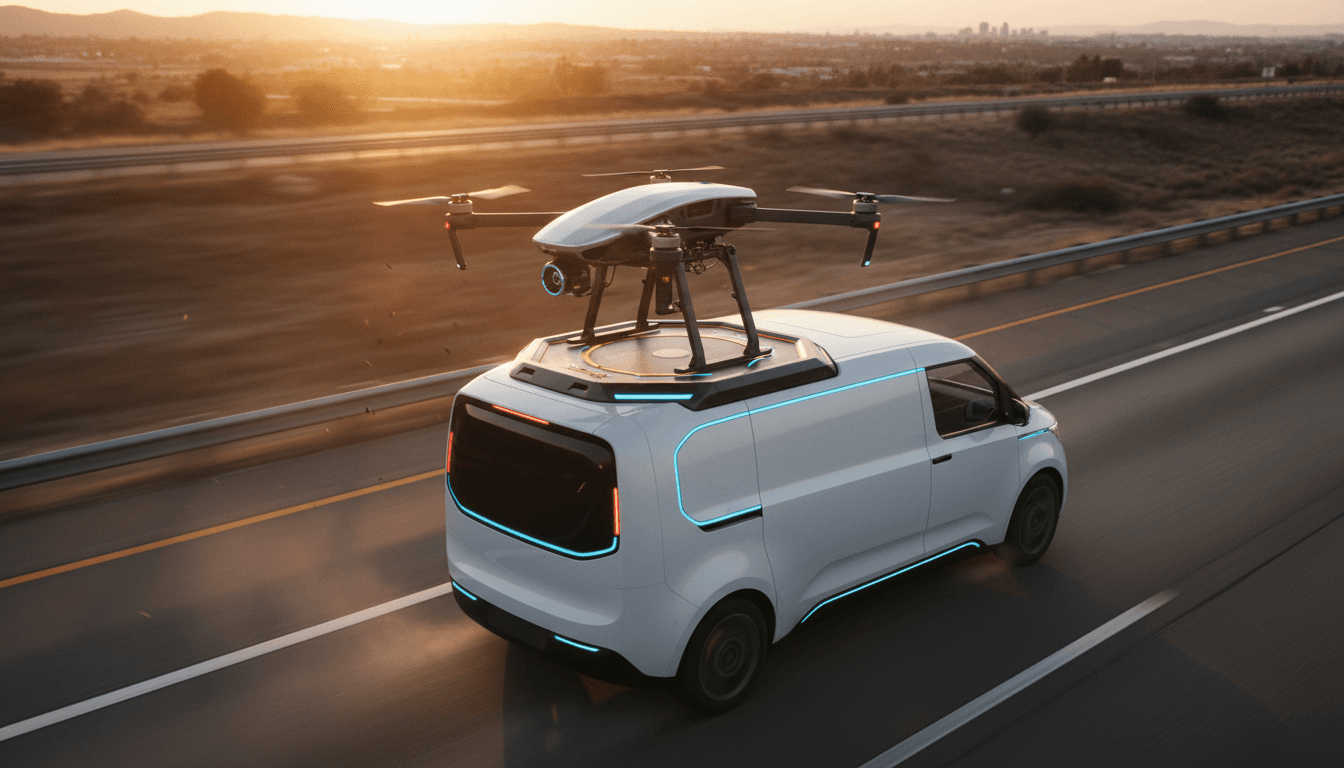

Drones Landing at 110 km/h: The Next Logistics Leap

A drone landing on a moving vehicle at 110 km/h isn’t a party trick—it’s a glimpse of where AI-powered robotics is headed: off the demo floor and into messy, real-world operations.

Most robotics “breakthroughs” don’t fail because the robot can’t fly, grip, or move. They fail because the last 5%—wind, timing, vibration, uneven terrain, unpredictable humans—breaks the system. This week’s batch of robotics videos (curated by IEEE Spectrum) is a useful snapshot of that reality: high-speed drone landings that tolerate chaos, open-source software that lets AI talk to robots, assistive arms that fit on wheelchairs, and yes, a robot hand doing a moonwalk parody.

This matters to anyone responsible for operations, innovation, or automation strategy. The reality? The winners in AI and robotics in industry won’t be the teams with the fanciest models. They’ll be the teams that make robots reliable under real constraints—and deployable by regular people.

High-speed drone landings are about reliability, not stunts

A drone that can land on a moving vehicle at highway speed solves a core problem in autonomous delivery and field robotics: how to end a mission safely and predictably when the “landing pad” is in motion.

The featured landing system pairs lightweight shock absorbers with reverse thrust, expanding the “landing envelope” so the drone can handle:

- Vehicle speed changes and vibration

- Wind gusts and turbulence around the vehicle

- Timing errors (arriving a fraction of a second early or late)

- Small alignment mistakes that would usually cause a bounce, tip, or slide

Here’s the key point: landing is where aerial autonomy becomes operational autonomy. A drone that can’t consistently land where you need it is a drone that needs humans on standby.

Where this shows up first: logistics, inspection, and emergency response

If you’re thinking “delivery vans,” you’re not wrong—but the higher value near-term opportunities often look like mobile work crews.

-

Utility inspection fleets

- A truck rolls along a corridor while a drone repeatedly launches to inspect poles, lines, or right-of-way vegetation.

- High-speed landing reduces stop-and-go behavior, improving crew productivity.

-

Road and rail incident response

- A responder vehicle becomes a mobile base station.

- The drone can scout ahead, map debris fields, or locate hazards, then land while the vehicle keeps moving.

-

Perimeter security and large-site patrol

- Think ports, mines, and industrial campuses.

- A moving vehicle can reposition to maintain comms, carry spares, and keep the drone operating longer.

For 2025 operations planning, the big shift is this: drones are turning into “tools that travel” rather than “assets that live at a fixed pad.” That’s a practical change in how you staff and scale drone programs.

What to ask vendors before you bet on mobile drone ops

If you’re evaluating AI-powered drone systems that claim “vehicle landing” or “mobile docking,” ask questions that expose operational maturity:

- What happens in crosswinds at 30–40 km/h? (Many systems are tuned for calm days.)

- How does the system handle GPS multipath and urban canyons?

- What’s the abort behavior? A safe go-around is more important than a perfect touchdown.

- How many landings between maintenance checks? Shock absorption is great—until parts wear.

- Can the system fail safely on a moving vehicle? (Tip-over on a truck roof is a bad day.)

If a vendor can’t answer with test ranges, failure modes, and maintenance schedules, you’re looking at a prototype—fine for R&D, risky for operations.

AI models talking to robots: why ROS-MCP-Server matters

The open-source initiative ROS-MCP-Server aims to connect AI models (like GPT-style assistants) with robots through ROS (Robot Operating System) using the Model Context Protocol (MCP). In plain terms, it’s part of a growing push to make robots easier to command, coordinate, and re-task using natural language.

This isn’t about replacing robotics engineers. It’s about removing the bottleneck where every new behavior requires a specialist to wire up interfaces, interpret sensor outputs, and write custom glue code.

The practical win: faster integration across “many small systems”

Most real deployments aren’t one robot doing one job forever. They’re messy stacks:

- A mobile base (AMR)

- A manipulator arm

- Multiple cameras

- A gripper and force sensor

- Safety scanners

- Fleet management software

- A workflow system (WMS/MES)

ROS already helps connect those pieces. MCP-style patterns add a missing layer: a structured way for an AI assistant to query context and act across multiple ROS nodes.

If it works as intended, the payoffs are tangible:

- Quicker prototyping: “Try a new pick strategy” becomes a conversation plus validation steps.

- Better supportability: technicians can ask why something failed (“Which sensor disagreed?”) and get a diagnostic trail.

- More accessible robotics: non-experts can run constrained actions (“Move to station 3, then scan bin labels”) without writing code.

A useful mental model: ROS connects robot components; MCP-style tooling connects robot behavior to intent.

The risk: natural language is not a safety spec

I’m optimistic about AI-to-robot interfaces, but I’m not naive about them. Natural language is ambiguous, and ambiguity is expensive when actuators can hurt people or damage inventory.

If you’re exploring AI-assisted robot control, set boundaries early:

- Use “intent → plan → execute” gates. The AI proposes; the system verifies.

- Restrict actions to approved skills. The assistant chooses from a menu; it doesn’t invent motor commands.

- Log everything. If a robot drops a part, you need a replayable chain of decisions.

- Treat prompts like code. Version them, review them, test them.

The best deployments will look boring: lots of guardrails, lots of validation, fewer surprises.

Cobots at 20: why collaborative robots became the default

Universal Robots marked 20 years since the first collaborative robot. The reason cobots became mainstream isn’t hype—it’s economics and usability.

Cobots succeeded because they fit factories as they are:

- They’re easier to install than traditional industrial robots.

- They’re well-suited to high-mix, low-volume work.

- They can be redeployed when a product line changes.

In 2025, the strategic shift is that cobots are increasingly paired with AI vision and more flexible end-effectors. That combination expands the set of tasks that are automation-viable:

- Kitting and light assembly

- Machine tending with variable part orientation

- Quality checks with visual inspection

The operational lesson: if your automation ROI depends on a perfectly controlled environment, you’ll spend your savings on exception handling. Cobots plus AI reduce exceptions by tolerating variation.

Assistive robotics is where “human-centered AI” becomes real

DLR’s assistive robot Maya is designed to integrate with a wheelchair and support people with severe physical disabilities. The engineering details matter here: stowing geometry, ground-level reach, and compatibility with standing functions aren’t nice-to-haves—they determine whether the system fits into daily life.

This is the version of robotics that doesn’t get enough attention in industry conversations. Assistive robots force clarity:

- Safety is not negotiable.

- Interfaces must be intuitive.

- Reliability matters more than peak performance.

And AI has a specific role: not “general intelligence,” but adaptive control and user intent interpretation.

What businesses can learn from assistive robot design

Even if you’re building warehouse automation, assistive robotics offers transferable lessons:

- Design for setup time (minutes, not hours).

- Prefer recoverable errors over brittle perfection.

- Make the robot’s next action legible to nearby humans.

If a device can work next to a wheelchair user in a crowded home, it can probably be made to work next to a technician on a shop floor.

Creativity, parody, and tennis balls: why robot videos still matter

A robot hand doing a moonwalk parody and humanoids struggling over tennis balls might seem like internet filler. I’d argue it’s useful signal.

Those clips expose what marketing rarely shows:

- Stability is hard.

- Contact-rich tasks are harder.

- The environment always wins eventually.

Meanwhile, the “real to sim” idea (captured in the feed as a playful jab at “sim to real”) reflects a serious trend: teams are increasingly using real-world data to build better simulations, rather than hoping a clean simulator will transfer perfectly.

If you’re investing in robot learning, push your team to treat simulation as a product, not a phase. The best pipelines:

- Gather data from reality (even small amounts)

- Update simulation parameters and edge cases

- Train policies and validate in sim

- Re-test in reality and repeat

That loop is how robots get robust enough to stop being babysat.

What to do next: a practical checklist for AI robotics teams

If your organization is evaluating AI-driven automation—drones, cobots, mobile robots, or assistive systems—these are the moves that reduce regret.

1) Pick a “robustness metric,” not a demo metric

Define success in operational terms:

- Mean time between intervention (MTBI)

- Recovery time after failure

- Percentage of missions completed end-to-end (including docking/landing)

2) Treat interfaces as strategy

Whether it’s ROS-MCP-Server or another approach, prioritize:

- Standardized robot APIs

- Observable state and replayable logs

- Clear permissioning and action constraints

3) Invest in the last 5%

Budget time for:

- Wind, dust, vibration, lighting changes

- Network dropouts

- Human unpredictability

- Wear-and-tear effects

That’s where projects either become products—or stay prototypes.

4) Plan for 2026 hiring and training now

By late 2025, the talent edge is shifting from “can we build a robot?” to “can we operate fleets?” Look for people who can bridge:

- Controls + software

- Safety + operations

- Data + robotics

Where this fits in the bigger AI & robotics story

This post sits squarely in the Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide series because it highlights what’s actually changing in the field: robots are getting more capable, yes—but the bigger shift is that they’re getting deployable.

High-speed drone landings show what robustness looks like in motion. ROS-MCP-Server hints at a future where commanding robots is less specialized and more scalable. Cobots remind us that adoption follows usability. Assistive robots set the bar for human-centered design.

If you’re building a roadmap for AI-powered robotics in 2026, ask one hard question: Which part of your workflow is still designed around a robot that can’t handle the real world?