Edible soft robots now include an ingestible battery, valve, and actuator. Here’s why biodegradable robotics matters for healthcare, agriculture, and AI-driven deployment.

Edible Soft Robots: The Battery Is Food, Too

A lot of robotics breakthroughs are about speed, strength, or precision. This one is about disappearing.

Researchers at EPFL in Switzerland built a soft robot that’s entirely edible—including the battery and the valve. Not “technically swallowable,” but made from food-safe materials that can be chewed and digested. That sounds like a novelty until you zoom out: if robotics is going to scale into farms, forests, waterways, and bodies, we can’t keep treating every deployment like it ends with a careful retrieval.

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and I think edible (and broadly biodegradable) robots are one of the clearest signals of where the industry is headed in 2026: robotics designed for the real world—messy environments, huge volumes, and strict safety constraints.

Why edible soft robots matter more than you think

Edible soft robots matter because they solve a problem that quietly blocks many “robots everywhere” visions: end-of-life.

A single robot is easy to manage. A swarm of thousands deployed across rough terrain, livestock areas, or disaster zones is a different story. Retrieval becomes expensive, incomplete, and sometimes impossible. If your business model requires large-scale deployment, you eventually face a choice:

- Pay for recovery operations that erase your margin

- Accept environmental waste and regulatory risk

- Build robots that biodegrade safely by design

Here’s the stance I’ll take: the third option is where the serious innovation is. And edible robotics is a very literal, very testable version of “safe-by-design.” If something is safe enough to eat, it’s usually safe enough to leave behind.

There’s also a second reason this matters: edible robots are a new form of human-robot interaction and animal-robot interaction. When a robot can be consumed, the “interface” isn’t a screen or a gripper—it’s chemistry, motion, smell, taste, and timing.

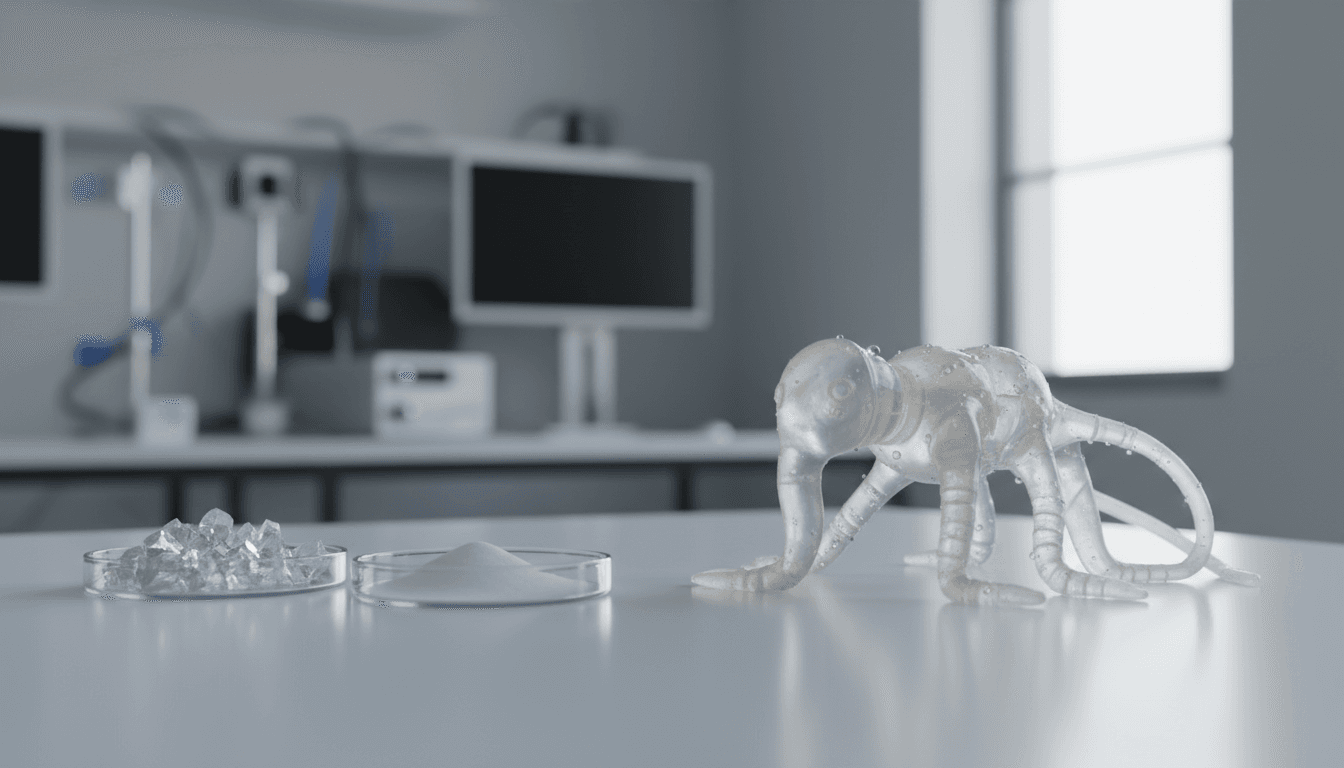

How EPFL’s edible robot actually works (battery, valve, actuator)

The key achievement from EPFL’s team (from Dario Floreano’s Laboratory of Intelligent Systems) is simple to state and hard to engineer: edible actuation with controllable motion, without relying on toxic batteries, metal valves, or plastic pumps.

The edible “battery” is a gas generator you can snack on

Instead of storing electrical energy like a lithium-ion cell, this robot’s battery stores chemical potential that gets converted into CO₂ gas pressure.

The edible battery is built from gelatin and wax, with chambers that hold:

- Citric acid (liquid)

- Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate)

A membrane keeps the ingredients separated. When pressure punctures the membrane, citric acid drips onto baking soda and produces:

- CO₂ gas (the working “power”)

- Sodium citrate (a common food additive)

That’s clever for two reasons:

- Pneumatics are naturally compatible with soft robotics. Gas pressure plays nicely with flexible bodies.

- Food chemistry is stable, cheap, and widely regulated. That’s a big deal if you’re designing for agriculture or healthcare.

The actuator is standard soft robotics—made ingestible

The robot’s motion comes from a familiar soft robotics structure: interconnected chambers on top of a slightly stiffer base. When pressurized, it bends.

Soft actuators like this are common in labs, but the snag has always been the supporting hardware—especially pumps and valves. EPFL’s approach avoids bulky hardware by generating gas on-board and routing it through gelatin tubing.

The valve is the real trick: snap-buckling for repeated motion

Continuous movement requires cycles: pressurize, release, pressurize again. To do that with edible parts, the team built an ingestible valve using a snap-buckling principle.

Snap-buckling means the valve “prefers” one stable shape (closed). When pressure rises high enough, it rapidly flips open, vents gas, and then snaps closed again as pressure drops.

In the current prototype, the robot achieves about four bending cycles per minute over a couple of minutes before the battery runs out.

That runtime won’t power a warehouse robot. But it doesn’t need to. Many high-value use cases in the wild (and inside bodies) only require short, controlled bursts.

One-liner worth remembering: If you can’t retrieve it, design it to become harmless.

Real-world use cases: animal health, field ops, and targeted delivery

The headline use case the researchers described is strikingly practical: delivering nutrition or medication to elusive animals.

Lead author Bokeon Kwak points to wild boars as an example—animals that are difficult (and risky) to approach, but attracted to moving prey. The robot’s wiggling actuator mimics that motion, and the payload could include something like a vaccine.

Agriculture: safer mass dosing without capture

Mass vaccination or dosing of wildlife and free-ranging animals often runs into the same bottlenecks:

- Capture is labor-intensive and stressful for animals

- Tranquilizers and handling introduce safety risk

- Baits can be consumed by the wrong species

Edible robots add a new control layer: behavioral targeting. By tuning motion, scent, taste, and size, you can bias which animals approach and consume the “bait.”

A realistic near-term pattern looks like this:

- Deploy edible soft robots in a defined area

- Use simple motion patterns to attract a target species

- Deliver a measured dose inside the edible body

- Let the device biodegrade fully if not consumed

Even if the robot is consumed by a non-target animal, the materials are food-safe by intent, not “oops-safe.”

Healthcare and ingestible robotics: fewer sharp edges, fewer retrieval problems

Ingestible robotics has a long-standing challenge: components like batteries, motors, and electronics complicate safety and disposal. An edible pneumatic system changes the design space.

It’s not hard to imagine a future pipeline where:

- An ingestible device performs a short task (mixing, expanding, positioning)

- It then dissolves into food-grade byproducts

- No retrieval procedure required

That’s especially attractive for pediatric and geriatric care where minimizing invasive follow-ups matters.

Environmental monitoring: disposable doesn’t have to mean polluting

Robots for environmental monitoring often get framed as “deploy and forget,” but the forgetting part becomes an ecological liability.

Edible/biodegradable soft robotics offers an alternative: short-lived devices that:

- operate long enough to trigger a measurement, release a tracer, or move to a micro-location

- then safely degrade

This is where the broader campaign theme shows up clearly: AI-powered robotics at scale demands sustainability, not as a branding exercise, but as an operations requirement.

Where AI fits: control, targeting, and “behavior as an interface”

This EPFL robot doesn’t need a neural network to wiggle. But the moment you treat edible robots as a platform—especially swarms—AI becomes the difference between a gimmick and a system.

AI turns motion into a targeting tool

If your goal is species-specific delivery, the robot’s movement becomes a kind of language. AI can help you design that language.

Examples of AI-driven improvements that are realistic in the next 12–24 months:

- Learned motion patterns that maximize approach rate for a target species while discouraging others

- Optimization models for scent/taste formulation under constraints (food-safe materials, shelf stability)

- Adaptive triggering (activate only under certain humidity/temperature conditions)

AI helps when you scale to swarms

Swarms aren’t just “more robots.” They change the management problem:

- You need consistent manufacturing quality

- You need predictable degradation timing

- You need deployment strategies that account for terrain and animal movement

AI planning tools can help decide:

- where to deploy for maximum uptake probability

- how many units are needed to reach a coverage target

- what failure modes are acceptable (and how to monitor them)

“Robot + payload” becomes a programmable product

The most interesting idea here isn’t that the robot is edible. It’s that the robot becomes packaging, actuator, and delivery mechanism in one.

That shifts product thinking:

- Instead of shipping pills and syringes, you ship behavioral delivery units

- Instead of relying on human compliance, you design for animal instincts

- Instead of retrieving devices, you design materials that naturally exit the system

Practical takeaways for leaders evaluating biodegradable robotics

If you’re in healthcare, agriculture, environmental services, or robotics R&D, edible soft robotics is worth tracking now—even if you’re not building gummy-candy actuators.

Here’s what I’d look at when assessing this class of technology.

1) Define success in minutes, not hours

These robots are built for short missions. Design your use case around:

- a small number of controlled actuations

- a narrow task scope (deliver, position, trigger)

- a clear end-of-life timeline

If your requirements start sounding like “continuous operation all day,” this isn’t the right tool.

2) Treat safety and compliance as first-class engineering inputs

Food-safe materials are only one piece. You also need to think about:

- allergens (gelatin sources, additives)

- dose accuracy and stability

- biodegradation byproducts under local conditions

The advantage is that food and pharma supply chains already understand these questions.

3) Plan for manufacturing simplicity

Floreano’s point about environmental and sustainable robotics is sharp: when you’re deploying many units, simplicity and affordability decide what scales.

A useful rule: if your biodegradable robot requires exotic fabrication, your “sustainable swarm” idea probably won’t survive procurement.

4) Don’t ignore the “wrong consumer” problem

If an edible robot is attractive, something will eat it. That’s the point—and the risk.

Mitigation strategies include:

- motion tuning (who is attracted to what)

- scent/taste shaping

- time-locked activation (only wiggle after exposure to a trigger)

- deployment timing (seasonality, feeding patterns)

The bigger picture: sustainable robotics is becoming a requirement

This work comes from the EU-funded RoboFood project, and it sits in a fast-growing trend: robots designed to be compatible with the environments they enter. In late 2025, that’s not a niche concern. Regulations on e-waste, pressure to reduce plastic pollution, and public scrutiny of field tech are all moving in the same direction.

Edible soft robots are a vivid proof point: we’re getting closer to robots that can operate in hard-to-reach places—inside an animal, across a forest, along a shoreline—without leaving behind the usual trail of batteries and polymers.

If you’re building AI and robotics strategies for 2026, here’s the question that keeps coming up for me: what would your deployment look like if retrieval was off the table from day one?

That’s where edible and biodegradable robotics stop being a quirky headline and start looking like a serious industrial design principle.