iRobot’s 35-year journey offers hard-won lessons in scaling AI robotics—product reliability, data risk, and why business models matter as much as autonomy.

iRobot’s 35-Year Lesson in AI Robotics at Scale

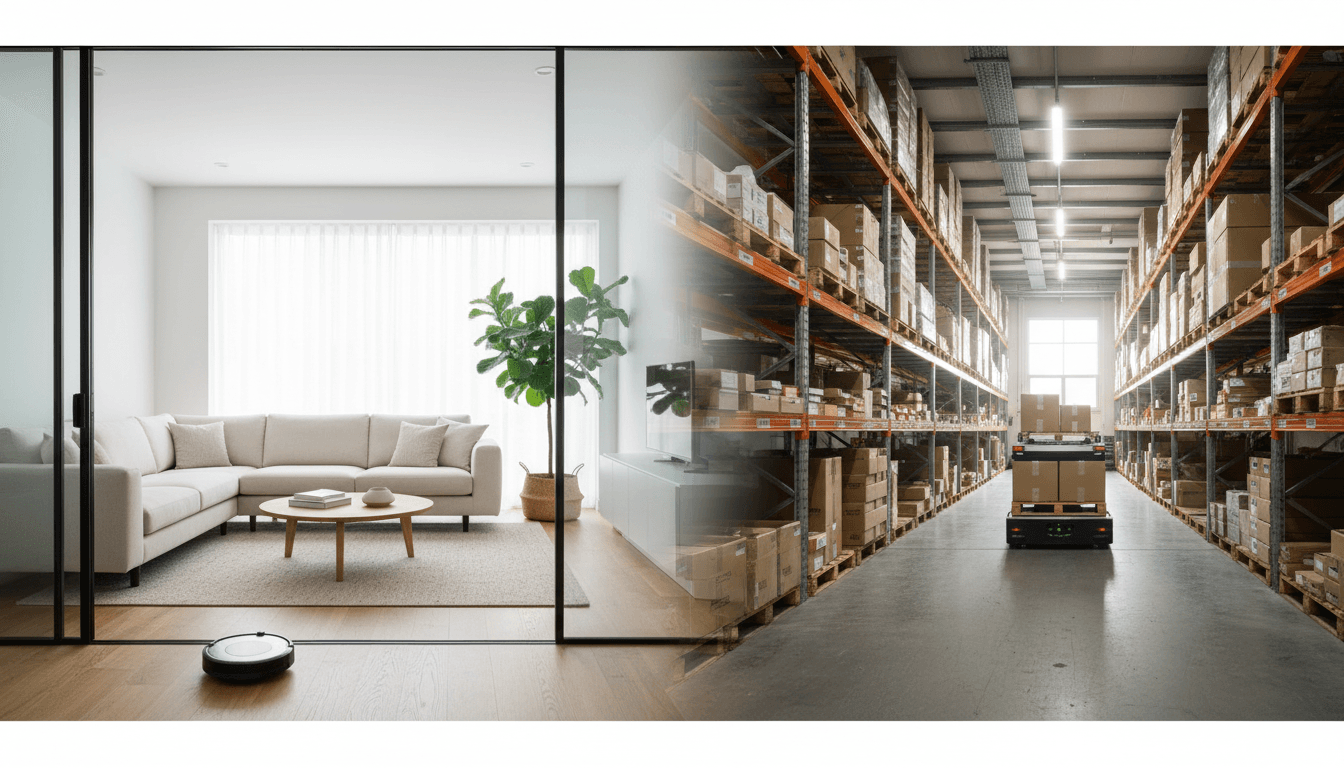

iRobot has sold 50+ million robots since 1990, and for a long stretch it was the rare robotics company that proved something many teams only talk about: autonomous robotics can scale into everyday life. That’s why its Chapter 11 filing (expected to wrap by February 2026) isn’t just business news—it’s a case study in what it takes to build AI-powered robots that survive contact with the real world.

I’m going to take a clear stance: iRobot’s story isn’t mainly about a robot vacuum. It’s about building a robotics “flywheel”—mapping, navigation, perception, reliability engineering, supply chain, and customer support—then discovering that those strengths don’t automatically protect you from pricing pressure, platform risk, and slow product cycles.

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and iRobot’s journey is a clean mirror of what’s happening across industries right now: AI is making robots smarter, but business models, data governance, and hardware economics decide who wins.

What iRobot proved: autonomy is a product, not a demo

The simplest takeaway from iRobot’s 35-year arc is this: autonomy becomes valuable only when it’s packaged as a dependable product that normal people can live with. That’s harder than building a one-off robot that works in a lab.

Roomba didn’t win because consumers fell in love with robotics research. It won because iRobot treated autonomy like a consumer appliance problem:

- Repeatable performance in messy homes (chairs, cords, pets, thresholds)

- Maintainability (filters, brushes, easy replacement parts)

- Trust (it runs without supervision, doesn’t break the house)

- Cost discipline (components, manufacturing, returns, warranties)

That’s the same checklist industrial robotics teams face in manufacturing, logistics, and healthcare. The robot is never “done” at launch; it’s “done” when it survives five years of edge cases, firmware updates, and customer behavior.

The hidden R&D behind “it just cleans”

iRobot’s early work—space exploration concepts like Genghis (1991) and mine detection robots like Ariel (1996)—sounds far removed from consumer floor care. But the throughline is consistent:

“The real product is mobility + sensing + decision-making under constraints.”

That’s the core of autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) in warehouses today. Different environment, same physics: imperfect sensing, partial information, and a need to act safely.

The timeline that matters (and why it maps to industry trends)

You can read iRobot’s history as three distinct eras, each matching a broader wave in AI and robotics adoption worldwide.

Era 1 (1990–2001): robotics funded by missions, not markets

iRobot started as a group of MIT engineers aiming at space, military, and industrial applications, largely supported by government contracts. That model is still common in frontier robotics: public funding helps build capability before there’s a clear commercial path.

The PackBot story is particularly instructive. Developed through defense work and deployed in real crises (including search operations after 9/11), it demonstrates a truth that applies in industrial settings too:

- Field deployments force robustness

- Robustness forces better engineering discipline

- Better engineering discipline becomes a competitive advantage—if you can carry it into a scalable market

Era 2 (2002–2016): consumer robots hit product-market fit

Roomba launched in 2002, and iRobot sold 1 million units in just over two years—a milestone many robotics companies still can’t touch.

This is the “scale era,” when consumer robotics proved it could become mainstream. The broader industry analog is what happened later with AMRs in logistics: once a robot starts paying for itself (time saved, labor reduced, fewer errors), adoption accelerates.

iRobot also experimented aggressively—Scooba, Dirt Dog, Create, Verro, Looj. Most didn’t stick.

Here’s the lesson for robotics product leaders: a portfolio is not a strategy if the company can’t sustain multiple product lines operationally. Every new robot adds QA complexity, supply chain risk, and support costs.

Era 3 (2016–2025): focus, globalization—and then margin collapse

In 2016, iRobot sold its military robotics business to focus on consumer products and expanded globally (notably opening an office in Shanghai). On paper, this looks like focus. In practice, it also increased dependence on a single category—robot vacuums—right when that category became brutally competitive.

By 2021, competition (especially lower-priced brands with comparable features) squeezed iRobot. The company tried to diversify with a handheld vacuum and acquired an air purifier company (Aeris) for $72 million, then discontinued that line in 2024.

From an AI robotics lens, this is a classic misstep: adjacent products still require distinct capabilities and distribution economics. Air purification isn’t “just another robot”—it’s a different market with different margins, channels, and replacement cycles.

Why iRobot struggled: three pressures every AI robotics company faces

The bankruptcy headlines are specific to iRobot, but the pressures are universal across AI and robotics companies worldwide.

1) Hardware gets commoditized faster than teams expect

Robot vacuums became a feature arms race: lidar vs. camera, mapping vs. no mapping, self-emptying docks, object avoidance, app features.

When competitors can deliver “good enough autonomy” cheaply, premium brands need one of two moats:

- A platform advantage (ecosystem, services, integrations)

- A performance advantage that’s obvious and sustained

If neither is clear, price wins.

2) Data is both an asset and a liability

Regulators looked hard at the proposed $1.7B Amazon-iRobot acquisition (announced in 2022, terminated in 2024). The concern wasn’t just market share; it was the strategic value of home data.

For AI robotics companies, the playbook is tricky:

- You want data to improve navigation and perception

- Customers want privacy and control

- Regulators want limits on how data is reused

A simple, defensible posture is becoming mandatory: collect less, retain less, explain more. If your product roadmap depends on expansive data use, your M&A and partnership options narrow.

3) Supply chain dependency can become a capital trap

In 2025, iRobot reported it had “no sources upon which it can draw for additional capital,” and its debt situation involved subsidiaries tied to its contract manufacturing relationships. That’s a reminder that robotics is not pure software: cash flow, inventory, and vendor terms can decide survival.

In industrial robotics, I’ve found the strongest teams manage hardware economics like a core competency, not a back-office function:

- Multi-sourcing critical components

- Designing for manufacturability early

- Planning warranty costs realistically

- Keeping SKU sprawl under control

What iRobot’s journey reveals about the future of automation

iRobot’s rise helped normalize robots in homes. Its current restructuring highlights where automation is heading next—both in consumer and industrial markets.

Trend 1: AI is shifting from “mapping” to “understanding”

Early home robots mostly answered: Where am I? and How do I cover the floor?

The next wave answers: What is this object? Is it safe to approach? What’s the best action?

That’s the same transition factories are making with AI-powered robotics: from fixed automation to adaptive automation—robots that can handle variability without constant reprogramming.

Trend 2: Human-AI collaboration is the real adoption engine

Robots succeed when they fit into human routines. Roomba worked because it didn’t demand new skills.

In warehouses and hospitals, the same principle holds: the best AMRs don’t require workers to “become roboticists.” They provide:

- Simple exception handling

- Clear status visibility

- Safe, predictable behavior around people

Trend 3: The business model will matter more than the robot

Hardware margins are thin. Services, consumables, and support are where profits often live. iRobot’s app and customer programs continuing through Chapter 11 shows how critical “robot operations” has become.

Across industries, the strongest automation deployments treat robotics as an ongoing operation:

- Fleet management

- Preventive maintenance

- Continuous improvement via software updates

- Performance measurement (uptime, cycle time, exceptions)

Practical takeaways for leaders adopting AI-powered robotics

If you’re a product leader, operations director, or innovation lead evaluating AI robotics in 2026 planning cycles, iRobot’s story suggests a more pragmatic checklist.

A due-diligence checklist that prevents expensive surprises

- Define success in operational metrics: uptime, mean time to repair, safety incidents, exception rates.

- Ask where autonomy breaks: lighting changes, clutter, reflective surfaces, narrow passages, mixed traffic.

- Plan the “last 10%”: docking, charging, recovery behaviors, user errors, and edge-case support.

- Get explicit about data: what’s collected, why, retention, access, and deletion.

- Model total cost of ownership (TCO): include training, maintenance, spares, and integration—not just purchase price.

A blunt opinion: focus beats breadth in robotics portfolios

iRobot’s experimentation produced valuable learning, but robotics companies often overestimate how many SKUs they can support.

If you’re building or buying robots, you’re usually better off with:

- One or two high-confidence deployments

- A repeatable rollout playbook

- A tight feedback loop between operations and engineering

That’s how AI-powered robotics scales without collapsing under support and integration debt.

Where this leaves the AI robotics market in 2026

iRobot entering Chapter 11 doesn’t mean consumer robotics failed. It means the market matured. Mature markets punish slow iteration, unclear differentiation, and fragile margins.

For the broader “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” trend, the more important signal is this: autonomy is now expected. The next competitive frontier is operational excellence—how reliably robots perform, how responsibly data is handled, and how quickly companies can improve deployed fleets.

If you’re considering AI-powered robotics for your business—whether that’s AMRs in logistics, inspection robots in utilities, or collaborative robots on factory lines—use iRobot’s 35-year journey as your shortcut. Build for real environments, treat data as a regulated asset, and never assume a great robot automatically equals a durable business.

What would change in your automation roadmap if you evaluated every robot not as a purchase—but as a five-year operational commitment?