Elephant crop raids spike near harvest—and water stress is a big reason why. Learn how AI risk maps, alerts, and water forecasting can support coexistence.

Farmers vs Elephants: Coexistence with AI & Water

Elephants can be sacred and still be a serious problem.

In northwestern Zimbabwe, many communities see elephants as a totem—an animal tied to identity, history, and respect. Yet as harvest season approaches, those same elephants often raid fields and crush months of work overnight. Researcher Agripa Ngorima, studying conservation attitudes in places like Simangani, put a practical question on the table: what changes when elephants bring benefits to villagers—meat, skins for ornaments, or other value—rather than only losses?

That tension—cultural reverence vs. livelihood risk—isn’t unique to Zimbabwe. It’s a pattern across Southern Africa where agriculture sits right next to wildlife corridors. And it’s exactly the kind of “messy” real-world system where AI in agriculture and AI for water management can help—not by replacing community decisions, but by giving them better options, better timing, and fewer surprises.

Why elephant crop raids spike near harvest

Answer first: Elephants raid crops near harvest because that’s when fields become the highest-calorie, lowest-effort food source—especially when natural forage and water are stressed.

By December (right now), much of Southern Africa is deep into the wet season, but rainfall variability has become the norm. Some areas get intense bursts and long dry gaps; others get late onset rains. When water is patchy, elephants do what any intelligent, social, energy-optimizing species does: they follow predictable food and water.

Crops are an “easy buffet”

Maize, sorghum, and other staples pack a dense energy payoff compared with browsing. Near harvest, these fields are also more aromatic and attractive. For a farming household, one raid can mean:

- A season’s food security wiped out

- Seed stock lost for the next planting

- Higher debt (if inputs were purchased)

- Retaliatory actions that escalate human-wildlife conflict

Water stress quietly drives conflict

Here’s the part many programs underplay: water availability is often the hidden variable behind crop raids. When pans dry up or rivers become intermittent, elephants expand their range. If farm plots are near boreholes, canals, or seasonal streams, they become “corridor-adjacent by default.”

This is where our campaign theme—जल प्रबंधन और पर्यावरण में AI—fits naturally. If you can forecast where water will be scarce, you can also forecast where conflict will rise.

The real coexistence debate: compensation vs. value-sharing

Answer first: Coexistence becomes realistic when communities have a predictable, fair system that turns wildlife presence into shared value—not just occasional compensation after damage.

Ngorima’s fieldwork (from the RSS summary) highlights a powerful idea: attitudes shift when elephants provide benefits. That could mean legal, regulated access to meat after problem-animal control, or income tied to conservation outcomes.

But I’ll be blunt: one-time payouts after a raid don’t fix the incentive structure. They can even create mistrust if payments are late, inconsistent, or disputed.

What “value-sharing” can look like (without romanticizing it)

Coexistence programs in Southern Africa typically draw from a mix of tools:

- Community-based natural resource management: revenue from wildlife-linked activities (where governance is strong)

- Performance payments: communities receive funds if conflict is reduced and habitats protected

- Regulated benefit use: strict rules around when and how communities receive material benefits

The catch is measurement. Who verifies a raid? How big was the loss? Was the elephant herd identified? Did deterrents run properly?

That measurement problem is exactly where AI-powered monitoring becomes useful.

Where AI actually helps (and where it doesn’t)

Answer first: AI helps most in prediction, early warning, and verification—turning conflict from a surprise into a managed risk.

AI won’t “solve” human-wildlife conflict by itself. Coexistence is political, cultural, and economic. But AI can reduce uncertainty and lower the cost of coordination—especially for agriculture departments, conservation bodies, and NGOs managing large landscapes.

1) Early warning systems for elephant movement

If you can detect elephant presence before they reach fields, response options expand.

Practical approaches include:

- Acoustic detection: microphones that pick up low-frequency rumbles and classify them

- Thermal or low-light camera traps: edge-of-field monitoring in high-risk weeks

- GPS collar data + geofencing: alerting rangers and community monitors when herds approach farms

AI’s role is pattern recognition and filtering. Communities don’t need 500 alerts; they need 3 alerts that matter.

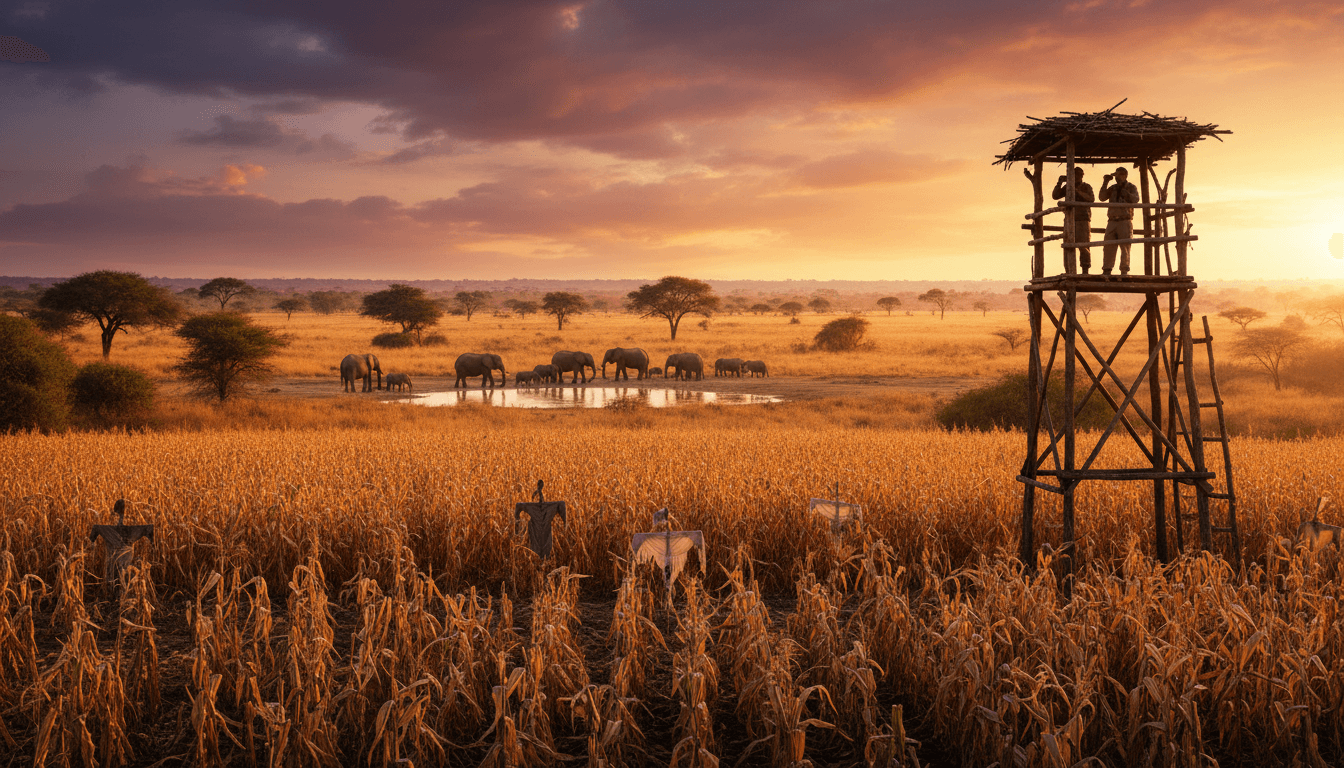

2) Risk maps that farmers can actually use

Satellite imagery plus machine learning can produce conflict risk maps that combine:

- Vegetation greenness (forage availability)

- Distance to water sources

- Crop type and crop stage (near-harvest = high risk)

- Historical raid locations

- Night-time darkness/lighting (elephants prefer cover)

A useful risk map doesn’t just show “red zones.” It tells you what to do:

- When to intensify night guarding

- Which boundary sections need quick deterrent repair

- Where to place watchtowers, lights, or beehive fences

This fits directly into the “कृषि और स्मार्ट खेती में AI” series: AI-based crop monitoring and stage detection isn’t only about yield—it’s also about protecting that yield.

3) Verification for faster, fairer compensation

If compensation exists, disputes kill it.

AI-assisted verification can combine:

- Time-stamped photos from farmers

- Satellite change detection (field damage patterns)

- On-ground ranger reports

The goal isn’t to police farmers. It’s to make the process fast, consistent, and trusted.

4) Water management as conflict prevention

This is the underused lever.

If AI models forecast water scarcity pockets two to six weeks ahead, programs can:

- Maintain alternative water points away from farms (where ecologically appropriate)

- Plan patrols and community support around predicted “high-pressure” weeks

- Protect canals and boreholes that attract elephants

Water planning is wildlife planning. Ignoring that is why many deterrent-only strategies fail.

Practical coexistence toolkit (low-tech + AI-ready)

Answer first: The most effective approach stacks multiple small defenses and pairs them with prediction—because elephants adapt quickly.

No single barrier holds forever. Elephants are smart, social learners. If one herd figures out a weakness, the trick spreads.

Field-level tactics that still matter

Many proven methods are not high-tech, but they become much more effective when guided by AI risk timing.

- Beehive fences: elephants often avoid bees; maintenance matters

- Chili-based deterrents: briquettes, ropes, or smoke; works best when deployed strategically

- Buffer crops: less palatable crops on the boundary (context-specific)

- Community night watch rotations: safer when coordinated and supported

What to “AI-enable” first (if budgets are tight)

If you’re choosing one starting point, I’d pick seasonal risk forecasting.

A simple, scalable setup:

- Use satellite-based vegetation and rainfall signals to flag high-risk wards

- Combine with local incident logs (even WhatsApp-based reporting)

- Send weekly advisories: “high-risk nights,” “priority boundary repairs,” “water stress alerts”

This is affordable compared to blanket collaring or dense camera networks.

Snippet-worthy line: “Coexistence fails when risk is random; it improves when risk is forecastable.”

People also ask: can AI reduce human-wildlife conflict without harming wildlife?

Answer first: Yes—when AI is used for prevention and planning, not for aggressive enforcement.

A common fear is that monitoring becomes surveillance or leads to harmful interventions. That risk is real if governance is weak. The safer model is:

- Community-owned data rules (who sees what, when)

- Minimum necessary monitoring (only what’s needed for alerts and verification)

- Non-lethal response as default

Another practical question:

Does this only work for large commercial farms?

Answer first: Smallholders can benefit more, because they’re the most vulnerable to a single raid.

AI doesn’t have to mean expensive hardware. In many pilots, the “AI layer” is centralized—processing satellite imagery and incident reports—while farmers receive simple guidance via SMS or local coordinators.

What a “better deal” looks like in 2026 planning

Answer first: The next generation of coexistence programs will tie together crops, water, and wildlife into one operational dashboard.

If you’re running a district agriculture office, a conservation project, or an agri-tech initiative, the smartest move for the next season is to stop treating these as separate problems.

A practical 90-day plan:

- Map hotspots: last 3 years of raid reports + crop calendars + water points

- Pick 2–3 interventions per hotspot (not 10)

- Add prediction: weekly risk bulletins driven by rainfall/vegetation signals

- Measure outcomes: raids per week, response time, crop loss estimates

- Align incentives: community benefits tied to verified reduction in losses

When the system is measurable, it becomes fundable. That matters for lead generation too: decision-makers want solutions they can defend in a budget meeting.

Where this fits in our “कृषि और स्मार्ट खेती में AI” series

This post is a reminder that smart farming isn’t only about squeezing more yield out of a field. It’s also about defending that yield against climate volatility, water stress, and ecological reality.

Southern African farmers living alongside elephants are already practicing a form of precision agriculture—just without the dashboards. Add AI-based crop monitoring, water forecasting, and early warning, and coexistence becomes less of a slogan and more of an operational plan.

If you’re building or buying agri-tech solutions in 2026, ask a tougher question than “Can it predict yield?” Ask: “Can it reduce avoidable loss—especially where water and ecosystems collide?”