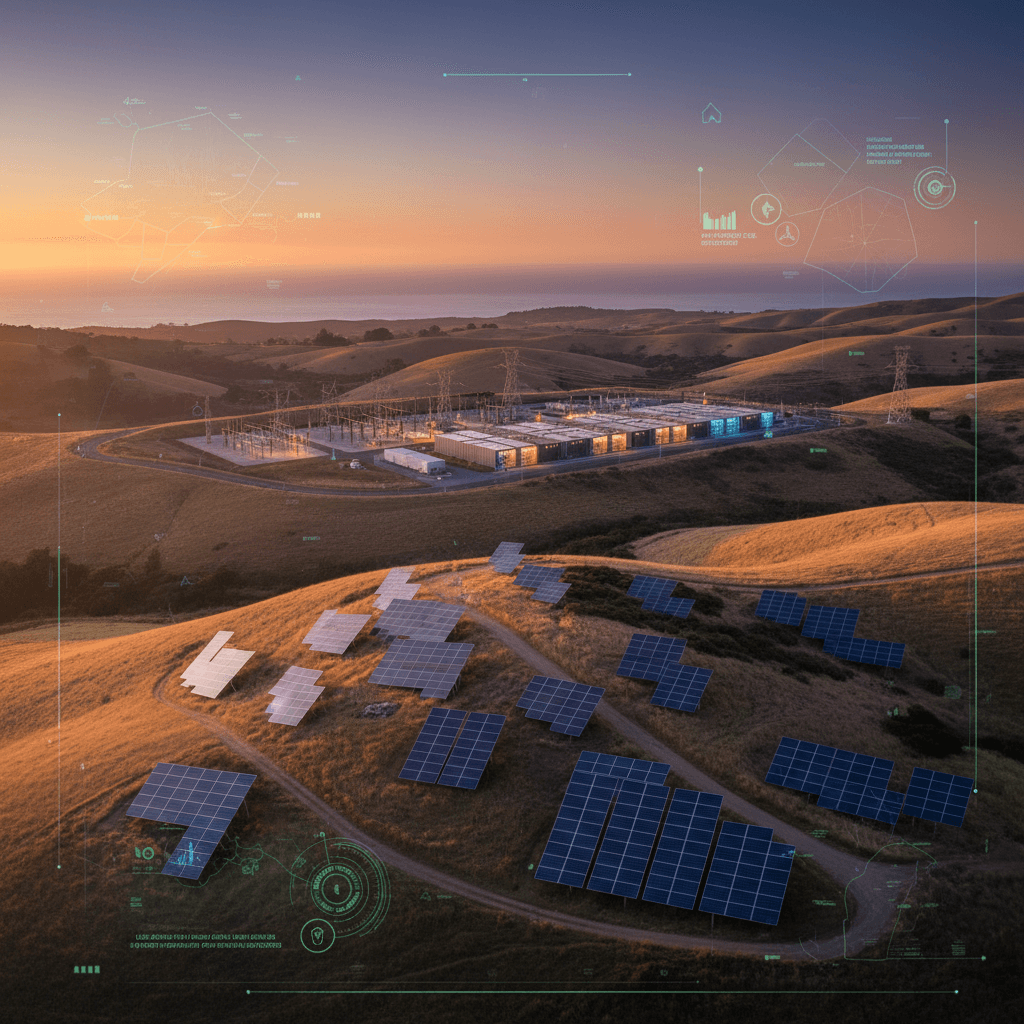

Santa Cruz’s new BESS zoning rules show how local policy, safety, and AI-driven planning are reshaping clean energy projects — and what it means for developers now.

Most clean energy bottlenecks in 2025 aren’t about technology. They’re about rules.

Santa Cruz County’s new draft zoning ordinance for battery energy storage systems (BESS) is a textbook example. While developers race to build storage to back up solar and wind, local officials are asking a different set of questions: Where can these systems go? How safe are they? Who’s responsible if something goes wrong?

This matters because the green technology transition isn’t just about smarter batteries and AI-optimized grids. It’s also about smart policy that communities actually trust.

In this post, I’ll break down what Santa Cruz is doing, why the delayed environmental review is a big deal, and how cities, developers, and businesses can use zoning, safety standards, and AI-driven planning to accelerate — not slow — clean energy.

Why Santa Cruz’s BESS Zoning Ordinance Matters

Santa Cruz County has published a draft zoning ordinance for battery energy storage systems and started the process for environmental review, which officials have already pushed back by roughly three months. On paper that sounds like dry local politics. In practice, it’s a preview of how communities everywhere will govern green technology.

Here’s the core move: instead of treating every new battery project as a one-off fight, the county is creating clear rules for where BESS can be built and under what conditions. That usually means:

- A zoning overlay that only allows grid-scale batteries on specific parcels

- Setbacks from homes, schools, and sensitive land

- Fire safety requirements and emergency access

- Environmental review thresholds and processes

Most regions across the US are now facing the same tension:

- The grid needs more storage to handle variable solar and wind.

- Residents are worried about fire, noise, and industrialization of rural land.

- Planners are trying to translate national climate goals into parcel-level decisions.

The Santa Cruz ordinance is part of a broader shift: energy storage is no longer a niche technology — it’s infrastructure, and infrastructure always ends up in the zoning code.

How BESS Zoning Actually Works (And Why Overlays Are Popular)

The reality? BESS zoning is simpler than many stakeholders think — if you break it down into a few core questions.

1. Where are large batteries allowed?

Counties like Santa Cruz typically use a zoning overlay for BESS. That’s a map-based layer that sits on top of existing zoning and says, in effect:

“Utility-scale battery projects are allowed here, here, and here — and nowhere else unless you meet stricter conditions.”

This approach helps:

- Protect residential neighborhoods and scenic corridors

- Concentrate infrastructure near transmission lines and substations

- Reduce speculative site control by developers in obviously unsuitable areas

For developers and investors, a zoning overlay may feel restrictive, but it offers one massive upside: predictability. If you know in advance which parcels are in play, you can focus due diligence, interconnection studies, and community engagement where projects actually stand a chance.

2. What counts as “small” vs. “large” storage?

Most modern ordinances draw a line between:

- Behind-the-meter systems (e.g., commercial battery paired with rooftop solar)

- Grid-scale BESS (tens to hundreds of MWh)

Small systems might be treated as an accessory use with streamlined permitting. Large ones usually trigger:

- Conditional or special use permits

- Environmental review

- Public hearings

Smart green technology policy doesn’t lump everything together. A 10 kWh residential battery isn’t the same beast as a 300 MW / 1,200 MWh utility system, and the rules shouldn’t pretend it is.

3. How are risk and safety handled?

Whether officials say it out loud or not, two concerns dominate every BESS hearing:

- Fire safety

- Environmental impact of failure

Modern fire codes (like NFPA 855) and UL testing standards for battery energy storage already cover a lot of ground: thermal runaway mitigation, gas detection, ventilation, emergency shutoff, and so on. Counties are increasingly baking these into zoning and permitting as mandatory conditions rather than optional guidelines.

Santa Cruz’s inclusion of BESS in its zoning process signals what I’ve seen repeatedly across the US: no fire and safety narrative, no social licence to build.

The Environmental Review Delay: Friction or Necessary Guardrail?

Planning staff in Santa Cruz have asked for more time — about three extra months — to complete environmental review of the BESS ordinance. For developers under pressure to bring green technology online, this sounds like yet another delay.

But here’s the trade-off that actually matters:

- Rushed rules can lead to blanket moratoria, lawsuits, and community backlash when the first large project comes forward.

- Well-studied rules create a durable framework that speeds up individual projects for years.

What environmental review usually looks at

For BESS zoning, environmental analysis typically examines:

- Land use conflicts: agriculture, open space, habitat, scenic areas

- Noise and visual impact: inverters, cooling equipment, lighting

- Fire and hazardous materials risk: worst-case scenarios and containment

- Cumulative impacts: what happens if multiple projects cluster in one area

The more that’s resolved at the ordinance level, the less each individual project has to re-litigate from scratch. In other words, a well-structured environmental review can front-load the hard conversations so future clean energy projects move faster.

Where AI and green technology fit in

This is where artificial intelligence quietly changes the game for both regulators and developers:

- Site screening with spatial AI: quickly rank parcels by environmental sensitivity, grid proximity, and community impact.

- Scenario modeling: simulate fire spread, noise propagation, and visual impact from different configurations.

- Grid impact forecasting: use machine learning to estimate how new BESS will affect local congestion, curtailment, and reliability.

Jurisdictions that adopt AI-assisted planning tools can shave months off environmental analysis while making it more robust. If your business provides these tools or data layers, ordinances like Santa Cruz’s are exactly where you should be in the room.

Designing BESS Projects That Actually Get Approved

Most companies get this wrong. They optimize for IRR and interconnection, then treat zoning as an afterthought. By the time they engage planners and neighbors, the design is basically fixed — and every requested change hurts the economics.

There’s a better way to approach grid-scale storage in communities like Santa Cruz.

1. Start with the zoning map, not the substation map

Developers understandably chase substations and transmission capacity first. But if those substations sit in areas that are politically toxic or outside any foreseeable BESS overlay, you’re burning time.

A more effective approach:

- Identify existing or likely BESS-eligible zones.

- Within those, prioritize parcels with:

- Direct access to transmission or distribution infrastructure

- Minimal sensitive receptors within key setback distances

- Compatible existing zoning (industrial, utility, or ag/industrial mix)

- Use AI-based tools to score and rank sites before spending heavily on interconnection studies.

2. Treat fire safety as a design driver, not a checkbox

Communities increasingly associate large batteries with high-profile fire incidents, even though the data show improving safety performance as technology matures.

To reduce that perceived and real risk:

- Use LFP (lithium iron phosphate) chemistries where possible; they have a lower thermal runaway risk than many NMC chemistries.

- Design with module-level isolation, gas detection, and early shutdown.

- Provide wide access lanes, clear labeling, and pre-incident plans for local fire services.

- Share results from large-scale fire tests and certifications that go beyond minimum compliance.

When a project team walks into a Santa Cruz-style hearing and can clearly explain how the design localizes failure, vents gases away from people, and supports firefighters, opposition loses much of its emotional punch.

3. Align benefits with local priorities

Battery projects are easier to approve when the value isn’t abstract “grid reliability” but something residents can see, feel, or save money on.

Examples that resonate:

- Solar + storage microgrids for critical facilities (hospitals, emergency shelters, water systems)

- Peak shaving that reduces pressure on local feeders and can help avoid expensive upgrades

- Participation in demand response programs that stabilize the California grid during heat waves

Framing the project as part of a smarter, cleaner local energy system — not a mysterious fenced-off box — is a communications strategy, but it should also be true in the technical design.

What Local Governments Can Learn From Santa Cruz

For counties and cities watching Santa Cruz, the lesson isn’t “copy their ordinance line by line.” It’s about the process.

Here’s what tends to work when regulating green technology like battery storage:

1. Create a dedicated BESS chapter in your code

For planners, forcing BESS into outdated categories like “warehouse” or “industrial use, n.e.c.” just creates confusion. A dedicated section in the zoning code that defines:

- BESS types and capacity tiers

- Permitted and conditional zones

- Setbacks, height, and screening

- Required safety features and studies

… gives everyone a shared starting point.

2. Coordinate zoning with fire and building officials

Too many ordinances are written in isolation. Better practice is to:

- Align zoning standards with NFPA 855 and current fire code

- Require pre-application meetings that include fire, planning, and building

- Allow staff to use performance-based criteria (e.g., maximum plume concentration at the property line) instead of rigid but outdated checklists

AI tools can help inspectors and fire marshals quickly review system layouts, simulate failure modes, and standardize permit conditions across multiple projects.

3. Bake community engagement into the process

When people feel BESS rules were designed behind closed doors, they fight each project individually. When they’ve had a say in where and how batteries can be built, there’s a shared sense of ownership.

Practical steps:

- Host public workshops before finalizing the ordinance

- Share easy-to-read visuals and scenario maps (this is where spatial AI and clear data visualization shine)

- Publish model conditions of approval so developers know what to expect

The goal isn’t unanimous support. It’s predictable, transparent decision-making that supports climate and resilience goals without blindsiding neighborhoods.

Where This Fits in the Green Technology Story

Battery storage zoning in a single California county might sound narrow, but it’s part of a much bigger pattern in green technology:

- Solar, wind, storage, EV charging, and microgrids are scaling fast.

- AI is making planning, operations, and optimization more efficient.

- Local rules — zoning, fire codes, environmental review — decide what actually gets built.

If your organization is developing BESS projects, building AI tools for site selection or grid modeling, or advising on sustainable infrastructure, this is the moment to lean in:

- Engage with local code updates early; don’t wait for ordinances to land on your desk.

- Bring data, not vibes — show modeled impacts, safety margins, and climate benefits in concrete numbers.

- Use AI responsibly to make your projects cleaner, safer, and easier to approve, rather than just more profitable.

Santa Cruz’s draft BESS ordinance and extended environmental review won’t be the last of their kind. They’re a glimpse of how green technology, public safety, and community values are going to intersect for the next decade.

If you’re serious about building the future energy system, this is the terrain you have to master.