Maine’s first major data center aims for zero-water cooling and renewable power. Here’s what it reveals about building truly green AI infrastructure at scale.

Why a Remote Air Force Base Matters for Green Tech

A single hyperscale data center can draw more electricity than a mid-sized city. Now put that kind of demand on a small, isolated grid in northern Maine and you’ve got a perfect stress test for what green technology at scale really means.

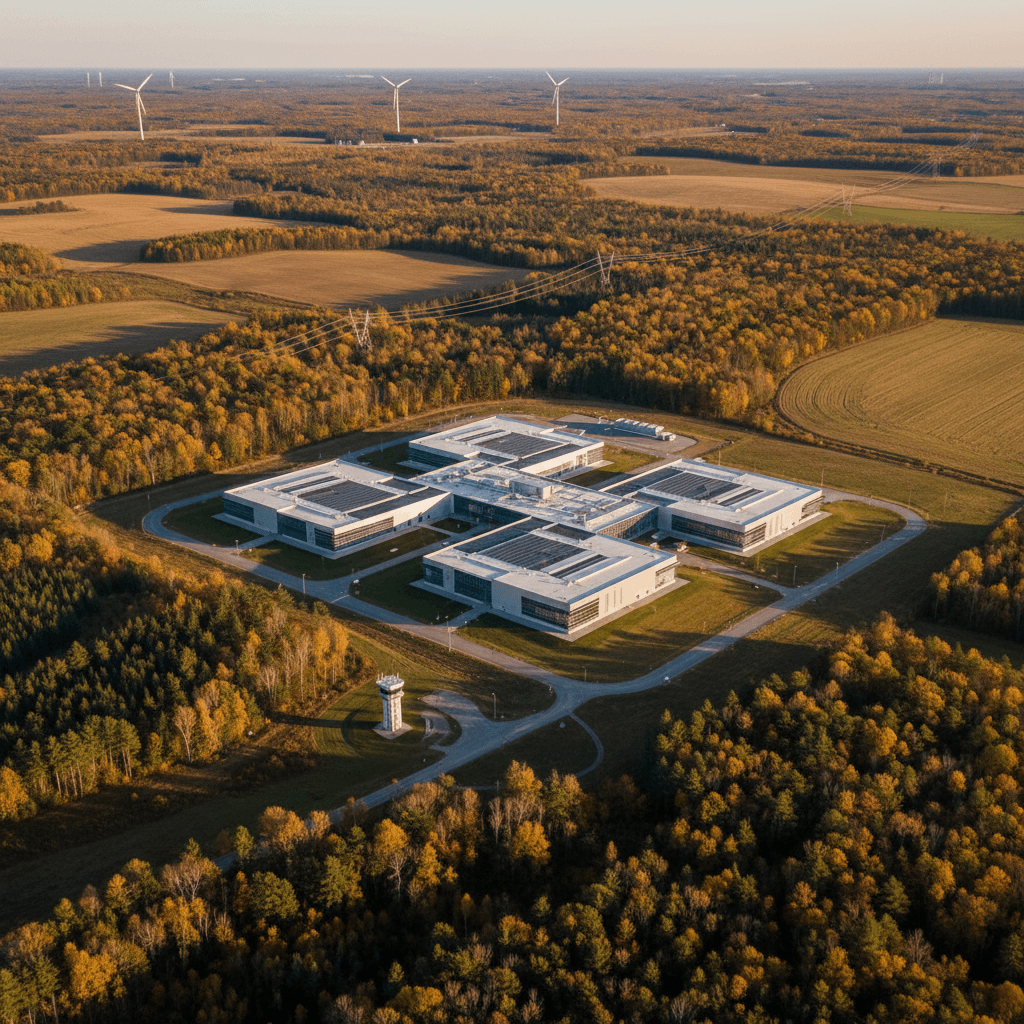

That’s exactly what’s happening at the former Loring Air Force Base in Limestone, where developers want to build Maine’s first major data center powered by renewable energy and cooled without using a single drop of water. For a region that’s struggled since the base closed in the 1990s, it’s an economic lifeline. For everyone else working in AI, cloud, or clean energy, it’s a live case study in how sustainable infrastructure either works—or backfires.

This project sits right at the intersection of our Green Technology series: AI workloads are exploding, data centers are racing to expand, and communities are asking hard questions about who pays the bill and who breathes the emissions. Loring’s story shows both the promise and the pitfalls.

The Vision: A Green Technology Campus on Old Military Ground

The Loring site is being repositioned as a green technology hub—not just a one-off facility. The base, already repurposed into a business park and commercial airport, is now part of a sustainability-focused campus developed by Green 4 Maine.

The core idea is straightforward:

- Use existing fiber infrastructure and a large, underused campus

- Power data center operations with renewable hydropower

- Replace traditional, energy-hungry cooling with immersion cooling

- Attract AI, cloud, and high-performance computing tenants that want low-carbon infrastructure

Developers plan to start with 2–6 megawatts (MW) of capacity and scale to 50 MW or more if demand justifies it. For context, northern Maine’s independent grid has a peak load of about 150 MW. At full buildout, this one data center could consume more than a third of the region’s total electricity demand.

Here’s the thing about that: scaling green technology isn’t just about replacing fossil fuel with renewables. It’s about whether the surrounding grid, community, and environment can handle the load without hidden costs.

Why Immersion Cooling Matters for AI and Sustainability

The Loring project is built around one big technical bet: immersion cooling from LiquidCool Solutions.

Instead of blasting cold air through server racks or piping in huge volumes of water, LiquidCool’s system submerges computer components in a non-conductive, oil-based fluid. That fluid absorbs heat directly at the source and carries it away—no fans, no chillers, no evaporative cooling towers.

Developers claim this offers several advantages:

- Lower energy use for cooling – Because heat is removed more efficiently at the chip level, cooling power consumption drops sharply compared to air conditioning.

- No water consumption – Critical in a world where many “cloud” facilities quietly draw millions of gallons from stressed watersheds.

- Minimal noise and no toxic byproducts – Better working conditions and fewer local pollutants.

For AI-heavy workloads, this isn’t just a sustainability perk. High-density GPUs and accelerators run hot. Conventional air cooling often forces operators to throttle density or overbuild cooling infrastructure. Immersion cooling lets you:

- Pack more compute into the same footprint

- Maintain performance under sustained, high-load training runs

- Extend hardware life by reducing thermal cycling

I’ve seen plenty of organizations sink money into “green” data centers that still use air cooling and then wonder why their power usage effectiveness (PUE) barely improves. If LiquidCool’s technology performs as advertised at Loring, it’s a credible template for AI-ready, low-carbon data centers that don’t quietly burn through water and electricity.

“We believe this technology is the endgame for cooling electronics,” says Herb Zien, vice chair of LiquidCool Solutions. That’s a bold claim—but not an unreasonable direction of travel.

What Businesses Should Take from This

If you’re planning AI or HPC expansion, you should be asking your data center providers:

- Are you using immersion or liquid cooling for GPU clusters, or are you still relying on air?

- What’s your PUE target and actual performance under AI-heavy workloads?

- How much water do your cooling systems consume per MWh?

Sustainable AI isn’t just about choosing a renewable tariff. It’s about whether the physical infrastructure is optimized for high-density, high-heat compute.

The Grid Reality: 50 MW on a 150 MW System

Here’s the uncomfortable part: adding 50 MW of demand to a small, isolated grid is a massive intervention, even if it’s mostly renewables on paper.

Northern Maine’s grid is separate from the rest of New England. It already relies heavily on imports from New Brunswick Power, including nearly 50 MW of mostly hydroelectric power available from a nearby substation. That sounds ideal, but there are caveats:

- There’s no signed supply agreement yet between New Brunswick Power and the developers.

- The local utility, Versant Power, has said grid upgrades will be needed, and while developers pay upfront, costs often show up later in retail rates.

- A Harvard Law study found that data centers frequently shift costs to ratepayers through special contracts and wholesale market structures.

The reality? Green technology projects can still create equity and affordability problems if they’re not structured carefully.

Questions Communities and Regulators Should Ask

If your region is courting data centers or AI infrastructure, you want clear, enforceable answers to these:

-

Who pays for grid upgrades, short- and long-term?

Not just initial capex—but O&M, contingency investments, and longer-term capacity expansions. -

Does the project crowd out other economic activity?

If a single facility uses a third of the available capacity, what happens to manufacturing, housing, or electrified transport projects that follow? -

Is the “100% renewable” claim contractually real?

Are there firm power purchase agreements, or just marketing language and assumptions about “available capacity”? -

What protections exist for ratepayers?

Transparent tariffs, caps, or regulatory oversight that prevent cost socialization while profits remain private.

Most companies get this wrong by focusing only on the carbon story. Carbon matters. But if local customers are paying higher bills to support “green” AI infrastructure, you’ll trigger backlash fast.

Diesel Generators, Backup Power, and Local Health

Even the cleanest data center designs usually include one dirty constant: diesel backup generators.

At Loring, developers plan to install on-site diesel units as standard reliability insurance. These generators typically only run 20–40 hours a year, according to data center researchers, but they still emit:

- Particulate matter (PM)

- Volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx)

In Limestone, that’s not a minor detail. The proposed site sits near the Mi’kmaq Nation and the Aroostook National Wildlife Refuge. If the grid performs well and outages are rare, local air impacts stay small. If reliability degrades or capacity is overstretched, those backup generators could run far more often than planned.

Developers say some future users might opt to operate without diesel backups. That’s encouraging, but not a guarantee.

Cleaner Backup Strategies to Consider

If you’re serious about green technology and you’re planning large compute loads, you should be pushing your providers on backup options:

- Battery energy storage systems (BESS) for short-duration ride-through events

- On-site renewable generation + storage for partial backup or peak shaving

- Green hydrogen or renewable gas generators where infrastructure exists

- Grid-interactive operations, where loads can ramp down during stress events

None of these are silver bullets, but they’re better than quietly assuming “we’ll rely on diesel and hope we don’t use it much.” Loring’s long-term credibility as a green data center hub will hinge on how seriously it treats backup emissions.

What Loring Teaches About Scaling Green AI Infrastructure

So what does this project actually tell us about the future of green technology and AI?

1. Cooling innovation is no longer optional.

Immersion cooling at scale isn’t a science experiment anymore; it’s a strategic necessity for AI-heavy facilities that want to lower power use, water consumption, and operating costs. If your AI roadmap assumes traditional air cooling, you’re behind.

2. “100% renewable” has to be backed by real contracts.

Marketing claims about hydropower access mean very little without firm agreements and transparent regulatory oversight. Smart customers—and smart regulators—will demand proof.

3. Small grids are the hardest test cases.

If a 150 MW grid can integrate a 50 MW data center without wrecking reliability or prices, that’s a strong validation of how to integrate large flexible loads elsewhere. If it fails, it’ll be a cautionary tale.

4. Community trust is a core asset.

Loring sits next to Indigenous lands and a wildlife refuge. If residents see primarily air pollution, opaque contracts, and rising rates, the “green” story collapses fast. True green technology aligns climate, health, and local economics.

For businesses hunting for sustainable AI infrastructure, this all boils down to due diligence:

- Ask where the electrons come from, not just what the brochure says.

- Demand clarity on cooling, water use, and backup systems.

- Look for partners who welcome regulatory scrutiny, rather than avoid it.

Projects like Loring are where theory becomes practice. If they succeed, they accelerate the entire ecosystem—AI, cloud, and green energy developers suddenly have a working playbook.

How This Fits Into the Bigger Green Technology Story

This blog series keeps circling back to the same pattern: AI is an energy story as much as a data story. Every new model, every new training run, sits on top of infrastructure that either reinforces fossil-based habits or pushes us toward a genuinely low-carbon economy.

The Loring data center proposal lands right in that tension. On one side, you’ve got:

- Immersion cooling that slashes energy and water waste

- A campus vision built around renewable power and green technology tenants

- Economic development for a rural region that needs it

On the other:

- Grid constraints that could affect reliability and prices

- Backup power choices that may impact local air quality

- Unanswered questions about who bears the long-term costs

This matters because similar choices are being made across North America and Europe right now. If you’re building, funding, or buying from AI infrastructure, you’re part of that decision chain.

My stance is simple: green technology has to work on the balance sheet, the grid, and the street. Projects like Loring can get there—but only if customers, regulators, and communities stay involved and demand real transparency.

If you’re evaluating where to run your next AI or data-heavy workload, use Loring as a checklist. Ask the hard questions before you sign. The cleaner, smarter infrastructure you insist on today is what will power your models—and your brand reputation—over the next decade.