COP30’s push to quadruple biofuels sounds climate-friendly. The reality: higher emissions, stressed food systems, and better green tech options being ignored.

Why COP30’s Biofuel Push Should Worry You

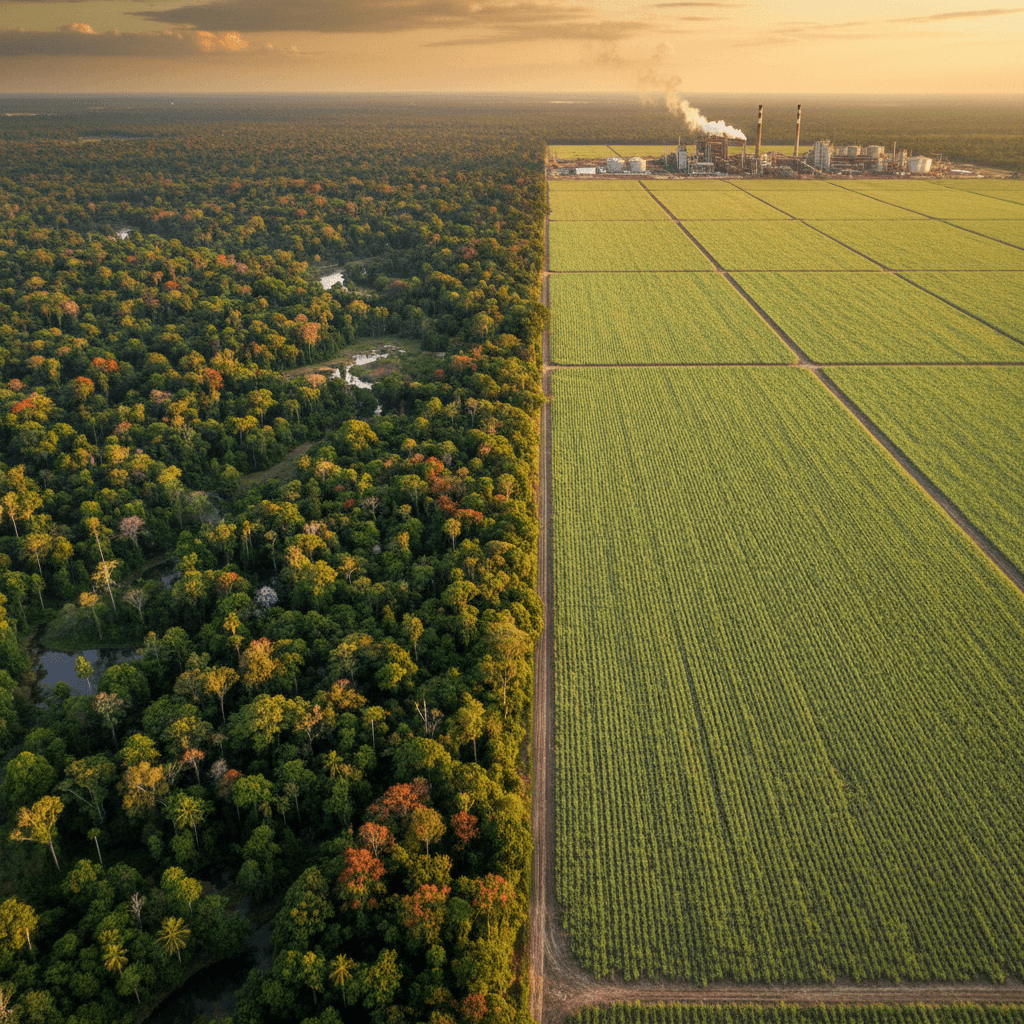

Global biofuel production has grown more than ninefold since 2000, and at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, a new pledge is pushing to quadruple “sustainable fuels” by 2035. On paper, that sounds like climate progress. In reality, it’s a bet that could deepen the food crisis, accelerate deforestation, and distract from cleaner green technologies that already work better.

Here’s the thing about biofuels: they were sold as a climate holy grail. Turn crops into fuel, burn “renewable” energy instead of oil, and everyone wins. But once you look at land use, food prices, and full life-cycle emissions, the story falls apart fast.

For anyone working in climate, clean energy, or green technology, this matters because you’re making decisions right now about where to invest time, money, and political capital. Doubling down on first‑generation biofuels is one of the easiest ways to lock the world into higher emissions and a more fragile food system — while better options are sitting on the table.

This post breaks down what’s really behind the COP30 biofuel pledge, why it’s such a risky strategy, and which green technologies offer a smarter path forward.

What COP30’s Biofuel Pledge Actually Wants

The Belém 4x pledge, led by Brazil, Italy, Japan, and India, aims to expand the use of so‑called sustainable fuels so that by 2035 they provide:

- 10% of global road transport demand

- 15% of aviation demand

- 35% of shipping fuel demand

Most of that “sustainable fuel” is expected to come from biofuels, today produced mainly from food crops like corn, sugarcane, soy, rapeseed, wheat, and palm oil. Alternatives like waste oils, forest residues, and algae exist — but they’re still tiny in comparison.

From a distance, it looks like a straightforward green technology story: swap fossil fuels for plant-based fuels, and emissions fall. That’s the narrative Brazil is promoting at COP30, pointing to its decades of experience with sugarcane ethanol as a model for Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

The reality? When you account for land-use change, fertilizer, processing energy, and indirect impacts on global agriculture, most large-scale crop-based biofuels don’t cut emissions — they increase them.

Why Crop-Based Biofuels Can Emit More Than Fossil Fuels

The key problem with first-generation biofuels is land. Plants do absorb CO₂ as they grow, but that doesn’t make a fuel climate-friendly by default. You have to look at the entire chain:

- Clearing forests or grasslands for new cropland

- Fertilizer and pesticide use

- Irrigation and water stress

- Energy for harvesting, transport, and processing

When all of that is counted, a global analysis from transport advocates found that biofuels currently emit about 16% more CO₂ than the fossil fuels they replace. That’s not a rounding error. It’s a structural problem.

Right now, more than 40 million hectares of cropland — an area about the size of Paraguay — are already devoted to biofuel feedstocks. At current trajectories, land equivalent to the size of France could be needed for biofuel crops by 2030.

There are two main ways this plays out:

-

More intensive agriculture on existing land

That means heavier fertilizer use, more pesticides, soil degradation, water pollution, and nitrous oxide emissions (a potent greenhouse gas). -

Expansion into new land

Forests and grasslands get cleared to grow energy crops. The carbon released from that land often wipes out any theoretical climate benefit for decades, sometimes longer.

Researchers like Jason Hill at the University of Minnesota have been blunt about this:

Biofuel production today is already a bad idea. Doubling it just doubles down on an existing problem.

If your green technology strategy requires turning carbon‑rich ecosystems into monoculture fields, it’s not a climate solution — it’s a land-use problem dressed in green branding.

The Food Security Collision: Fuel vs. People

When governments mandate biofuel use, they don’t just tinker with energy markets. They hardwire demand into the system. That has direct consequences for food prices and availability.

A 2022 analysis of the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard, the world’s largest biofuel program, found that:

- Corn prices rose by about 30%

- Soybean and wheat prices increased by about 20%

- Fertilizer use climbed up to 8%

- Water quality degradants increased up to 5%

And the kicker: the carbon intensity of corn ethanol produced under that mandate ended up at least as high as gasoline.

When you apply that dynamic globally, especially under rigid mandates, a few things happen:

- Baseline fuel demand is inflexible. Even during droughts or crop failures, the biofuel quota must be met.

- Food supply tightens. More land and crops flow into fuel, not plates.

- Prices spike. Vulnerable populations feel it first and worst.

Ginni Braich, a data scientist with experience advising clean tech and emissions programs, put it crisply: biofuel mandates create baseline demand that can leave food crops by the wayside.

From a nutrition standpoint, there’s another subtle but serious impact:

- Farmers shift to a narrower set of high-demand fuel crops (corn, soy, sugarcane).

- Diets become less diverse and more fragile.

- Local food systems lose resilience as land concentrates on export‑oriented energy crops.

Layer that on top of climate stress, conflict, and economic volatility, and you’re not just talking about fuel policy. You’re talking about global food security.

The Green Technology Perspective: Better Options Exist

If crop-based biofuels are this problematic, what should serious climate strategies focus on instead? Here’s where the broader green technology picture matters.

1. Electrification where it works now

For road transport, the smartest decarbonization tool we have is still electrification:

- Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) for cars, vans, and buses

- Electric two- and three-wheelers in urban and emerging markets

- Grid upgrades, smart charging, and storage to integrate renewables

Every major lifecycle study shows that EVs powered by an increasingly clean grid slash emissions far more reliably than crop-based biofuels — with no land-use penalty.

2. True advanced fuels for hard-to-abate sectors

Aviation and shipping are harder. But even there, not all “sustainable fuels” are equal. Green technology efforts should prioritize:

- E-fuels made from green hydrogen and captured CO₂, using renewable electricity.

- Genuine waste-based fuels, where the feedstock is a real residue (used cooking oil, forestry slash, organic waste) that doesn’t trigger land expansion.

- Green ammonia and methanol for shipping, paired with strict sustainability criteria.

These pathways aren’t trivial. They’re capital-intensive and technically challenging. But they don’t depend on displacing food crops or clearing forests, and they integrate directly with the broader clean energy system.

3. AI and data as force multipliers

Since this post is part of a Green Technology series, it’s worth calling out where AI and digital tools change the game:

- Spatial planning and land-use modeling to identify where any biomass use is truly sustainable — and where it’s a red flag.

- Supply chain traceability using remote sensing, machine learning, and blockchain to verify that “sustainable” fuels aren’t quietly driving deforestation.

- Grid and fleet optimization to make electrification cheaper and more reliable than sticking with liquid fuels.

- Scenario analysis to compare pathways: e.g., “What happens to emissions, land, and food prices if we push EV adoption vs. biofuel mandates in Country X?”

I’ve found that the highest‑leverage climate projects use AI not to justify old assumptions, but to expose them. When you model land, water, food, and emissions together, biofuels stop looking like a climate solution and start looking like a constraint.

How Policymakers and Businesses Can Avoid the Biofuel Trap

If you’re drafting policy, running a sustainability team, or investing in green tech, here’s a more responsible way to approach fuels:

1. Draw a hard line on food-based biofuels

- Phase out mandates that rely on primary food crops (corn, soy, sugarcane, palm oil, wheat, rapeseed).

- Cap total demand for crop-based biofuels instead of promising long-term expansion.

- Align national policies with full life‑cycle accounting, including indirect land-use change.

2. Set strict sustainability criteria for any biomass

If biomass is used at all:

- Require proof that feedstocks come from true waste streams or residues.

- Exclude material from lands cleared after a specific cutoff date.

- Track and publicly disclose land-use, water, and biodiversity impacts alongside CO₂ metrics.

3. Prioritize electrification by design

For fleets, logistics, and municipal procurement:

- Create EV‑first policies: evaluate electric options before considering any liquid fuel.

- Use AI-supported route planning and charging optimization to cut cost and range anxiety.

- Invest in charging networks, grid flexibility, and distributed storage ahead of fuel blending infrastructure.

4. Treat “sustainable fuels” as a scarce, premium resource

Instead of trying to pour alternative fuels into every tank on Earth, treat them like this:

- Reserve genuinely sustainable fuels for sectors and routes where electrification is structurally hard.

- Avoid blanket volumetric targets that ignore resource limits.

- Tie any incentives to measurable, independently verified emission reductions.

This is where serious climate strategies diverge from greenwashing. One is shaped by physical limits — land, water, carbon, nutrients. The other is shaped by lobbying and wishful thinking.

Where the Green Technology Story Should Go Next

Biofuels have become a kind of comfort blanket in climate negotiations: a way to promise big emission cuts without changing much about how vehicles, supply chains, or cities actually work. COP30’s push to quadruple “sustainable fuels” is another chapter in that story.

There’s a better way to think about this transition. We’re not short on green technology options; we’re short on discipline. Electrification, true waste-based fuels, green hydrogen, smart grids, and AI-driven planning are all more scalable, more measurable, and less risky than turning ever more farmland into fuel.

The question for the next decade is blunt:

Do we want a climate strategy that competes with food and forests, or one that makes both more resilient?

If you’re building or funding climate solutions, now is the moment to decide which side of that line you’re on.

If your organization is rethinking its transport or energy strategy and wants to stress‑test it against land, food, and climate risks, this is exactly where modern green technology and AI shine. Designing a low‑carbon pathway that doesn’t backfire on food security isn’t just possible — it’s becoming the new baseline for credible climate action.