Tyson just dropped its “climate smart beef” label after a lawsuit. Here’s what that means for greenwashing, climate‑smart food systems, and real solutions.

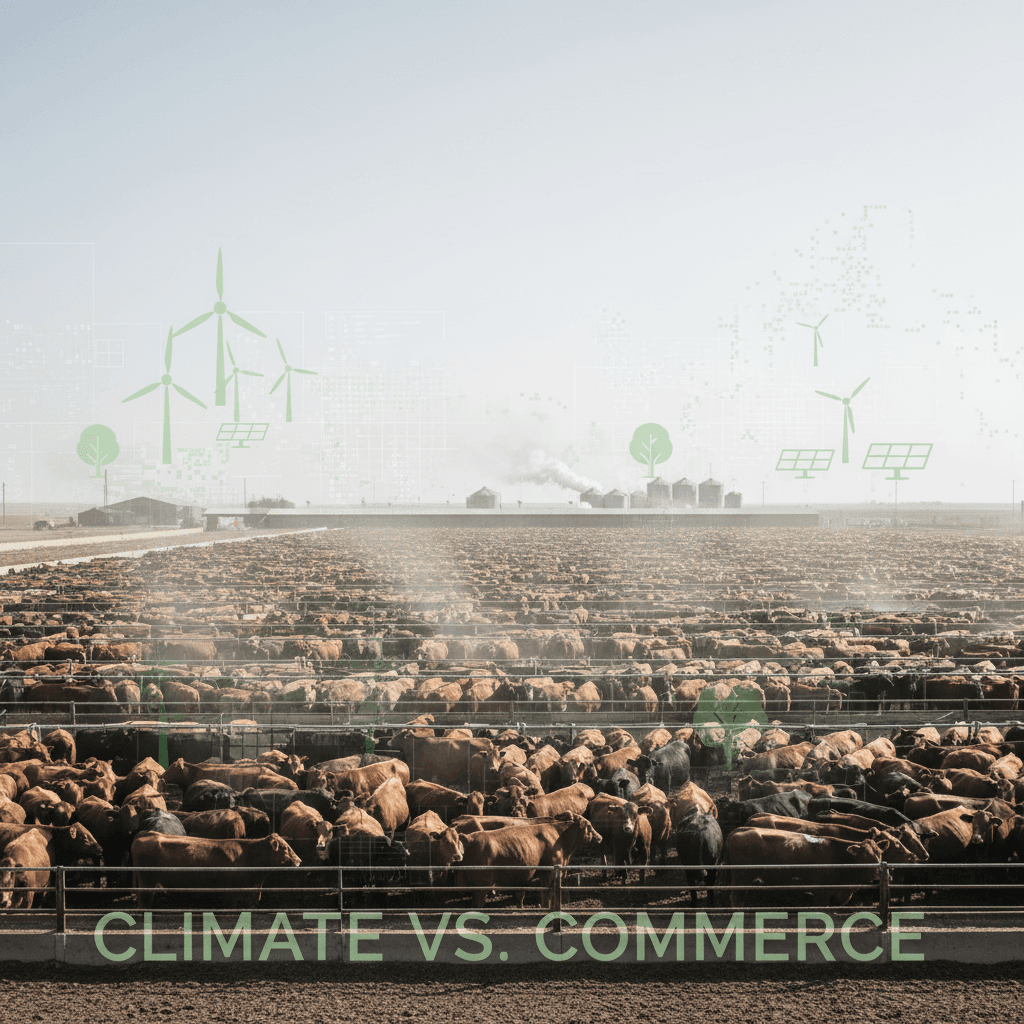

Our food system now accounts for roughly one‑third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and beef is the heavyweight: per gram of protein, beef produces around two and a half times the emissions of lamb and nearly nine times that of chicken or fish. So when a company that controls about 20% of U.S. beef, chicken, and pork starts selling “climate smart beef,” it’s going to attract attention — and scrutiny.

That scrutiny just paid off. After a lawsuit from environmental advocates, Tyson Foods has agreed to drop its “climate smart” beef label and step back from unverified net‑zero claims. This isn’t just a branding tweak. It’s a signal that the era of vague, feel‑good climate labels in industrial agriculture is running out of road.

Here’s what this case tells us about greenwashing in meat and dairy, why it matters for climate‑conscious consumers and green‑tech businesses, and what actual climate‑smart food systems look like.

What Tyson’s “climate smart beef” settlement really means

Tyson didn’t just quietly update packaging. Under a five‑year settlement, the company agreed to:

- Drop unverified net‑zero claims: No more saying it has a plan to reach net‑zero emissions by 2050 unless that plan is independently verified.

- Stop using “climate smart” or “climate friendly” on beef in the U.S. unless a third‑party expert backs the claim.

- Define and substantiate any future climate claims with an expert agreed upon by both Tyson and the Environmental Working Group (EWG), which brought the case.

Earthjustice, which represented EWG, framed this as consumer protection: if a company wants to sell you on “climate smart” anything, it needs to show its work. I think that’s the bare minimum.

Here’s the thing about beef and climate: in industrial systems, “climate‑smart beef” is essentially an oxymoron. Even if Tyson managed a 10–30% emissions cut through feed additives, better manure management, or energy efficiency, beef would still sit at the top of the emissions chart per gram of protein. That doesn’t mean incremental improvements are pointless, but it does mean they shouldn’t be sold as a climate solution comparable to, say, plant‑based proteins or regenerative cropping.

The settlement doesn’t solve industrial agriculture’s climate problem. But it does tighten the rules of the game: if you want the marketing glow of climate claims, you now face higher legal risk if those claims are woolly.

Why greenwashing is so easy in industrial agriculture

Greenwashing thrives where data is weak, standards are loose, and accountability is rare. Industrial meat and dairy hit that trifecta.

1. Emissions data is patchy and often voluntary

Unlike power plants or carmakers, most meat and dairy companies aren’t under consistent, binding requirements to disclose their emissions, especially from supply chains. When they do report, three problems show up again and again:

- Voluntary disclosure: Companies decide what to publish and what to exclude.

- Non‑standard methods: Different baselines, different accounting rules, hard‑to‑compare numbers.

- Gaps in scope 3 emissions: The biggest chunk of emissions — from feed, land‑use change, and methane from animals — is the hardest to measure and easiest to fudge.

A recent scorecard of 14 of the world’s largest meat and dairy companies ranked them on transparency and climate action. Tyson and JBS, the two giants that have now faced greenwashing suits, tied for the lowest score. That’s not a coincidence.

2. Vague language, zero hard commitments

Phrases like “net zero by 2050” or “climate smart beef” sound serious but often hide the lack of a concrete pathway:

- No clear interim targets (e.g., 50% reduction by 2030)

- No detailed breakdown of how reductions vs. offsets will work

- No transparent budgets for methane cuts, feed innovation, or land‑use change

The lawsuit against JBS in New York ended in a $1.1 million settlement and a forced downgrade of its “net zero by 2040” language from firm commitment to aspirational idea. That’s a big tell: if it was a real plan, they’d have defended it.

3. Secrecy is baked into the model

Industrial animal agriculture is built on opaque supply chains: contract growers, complex feed sourcing, and vertically integrated operations. This structure makes it incredibly hard for outsiders — or even regulators — to pin down who’s responsible for what.

Advocates describe the sector’s business model as “built on secrecy.” When there’s little public data and high complexity, the marketing department can run far ahead of the sustainability team.

What this means for climate‑conscious consumers

Most people reading a label like “climate smart beef” aren’t experts in life‑cycle assessment. They’re just trying to do less harm at the grocery store. The Tyson case changes the landscape in a few useful ways.

How to read climate claims on food labels

If a product claims to be “climate smart,” “carbon neutral,” or “net‑zero aligned,” you can assume one of two things is true:

- The company has done the hard work of measuring, reducing, and transparently reporting its emissions; or

- The company is hoping those words are enough to convince you without giving you anything to verify.

Until regulation fully catches up, I’d treat every climate claim as a hypothesis that needs testing. Look for:

- Specifics over slogans: “30% lower emissions than the national beef average, validated by an independent auditor” is very different from “climate smart.”

- Independent verification: Third‑party audits, standards, or certifications with clear criteria.

- Actual trade‑offs: A serious company will admit where it’s still high‑emitting and what it can’t solve yet.

If none of that is visible, assume marketing is doing more work than the science.

Want a lighter climate impact? Control what’s on your plate

Legal fights are useful, but they won’t decarbonize dinner on their own. From a climate perspective, the hierarchy is blunt:

- Eat less beef, especially from industrial feedlots. Even swapping one or two weekly beef meals for chicken, beans, lentils, or tofu shifts your footprint meaningfully.

- Favor lower‑impact proteins. Poultry, eggs, and most plant proteins are dramatically less carbon‑intensive per gram of protein.

- Support producers with transparent practices. Smaller regenerative or pasture‑based systems aren’t emission‑free, but they often have clearer, verifiable climate and biodiversity practices.

I’ve found the most sustainable eating pattern is the one you can actually stick to. You don’t need to become vegan overnight. But if a label is doing the heavy lifting of easing your conscience, stop and ask whether the data backs it up.

Why this matters for green tech and climate‑focused businesses

If your work touches green technology, sustainability reporting, or climate‑smart agriculture, the Tyson and JBS cases are flashing neon signs: vague climate claims are now a legal, financial, and reputational risk. That’s a huge opening for serious solutions.

1. Demand for real measurement is about to spike

Upcoming climate disclosure rules in places like California and the European Union are pushing big companies toward standardized, auditable emissions reporting — including supply chains.

For green technology companies, this creates concrete opportunities:

- MRV tools (measurement, reporting, verification) for methane and nitrous oxide on farms

- Remote sensing and AI for tracking land‑use change and deforestation linked to feed

- Data platforms that integrate farm‑level data into corporate climate reports

Most agri‑food giants aren’t ready. Those that move first with robust measurement will be safer from lawsuits and more attractive to investors. Those that stall will keep tripping over their own marketing.

2. Transition finance beats green PR

Investors, lenders, and corporate buyers are starting to distinguish between:

- Companies with credible transition plans (short‑term targets, capex aligned to decarbonization, clear governance), and

- Companies bathing themselves in “net zero” language while expanding high‑emissions business lines.

Tyson’s and JBS’s settlements are small, financially speaking. But they set a precedent: climate claims are no longer free. For capital providers, that means:

- You’ll need better diligence on climate narratives versus real performance.

- There’s upside in backing plant‑based, fermentation‑based, and cellular agriculture that actually remove emissions from the system rather than rebrand them.

The reality? The cheapest ton of “abated” carbon is still the one you never emit. Technology that avoids emissions — by replacing high‑impact products or redesigning systems — is far more valuable than clever offset schemes.

3. Policy and green tech are starting to align

As disclosure rules and anti‑greenwashing enforcement tighten, they create demand for the very tools the green tech sector builds:

- Better on‑farm sensors and analytics to quantify methane

- Low‑emissions feed additives that measurably cut enteric methane

- Manure management and biogas systems with transparent performance data

- Plant‑based ingredient innovation that makes lower‑carbon foods more convenient and desirable

If you work in these areas, the Tyson case is free marketing for you. It tells the market: hand‑wavy claims are out; verifiable performance is in.

What real climate‑smart food systems look like

If “climate‑smart beef” is mostly branding, what deserves the climate‑smart label?

I’d put three things on that list:

1. Shifting protein demand

The fastest, lowest‑cost climate lever in food is eating fewer high‑emission products. That doesn’t require new hardware or huge capex. It requires:

- Better plant‑based options that are affordable and widely available

- Public procurement policies that favor low‑carbon menus in schools, hospitals, and canteens

- Clear communication that diets with less beef are normal, tasty, and culturally adaptable

2. Transforming production systems

Where animals stay in the system, meaningful climate action looks like:

- Clear emissions baselines and targets at farm and company level

- Methane‑reducing innovations (feed changes, breeding, manure digestion) with third‑party verification

- Land‑use strategies that avoid deforestation, restore degraded land, and protect carbon‑rich ecosystems

These aren’t “nice to have” CSR projects. They’re the basic cost of doing climate‑honest business.

3. Radical transparency

Without transparency, everything else is just promises. Real climate‑smart systems:

- Publish farm‑to‑fork emissions data using consistent methods

- Invite independent audits and actually act on the findings

- Avoid buzzwords that can’t be quantified and compared

Consumers don’t need perfection. They need honesty and progress they can see.

Where this leaves you — and what to do next

Tyson dropping its “climate smart” beef label doesn’t fix industrial agriculture’s climate problem. It does something more specific but still important: it raises the cost of lazy climate marketing.

If you’re a consumer, the most climate‑positive moves you can make are straightforward: eat less industrial beef, favor lower‑impact proteins, and treat every climate label as a claim that needs real evidence, not trust.

If you’re building or investing in green technology or sustainable food businesses, use this moment. Position yourself on the side of verifiable impact:

- Help companies accurately measure and report emissions.

- Design products that genuinely displace high‑emission foods.

- Build business models that don’t depend on empty climate slogans.

The fight over “climate smart beef” is really a fight over who controls the story of climate progress: the marketing department, or the data. The sooner data wins, the better for the climate — and for the companies that are actually doing the work.