Climate finance finally hit $100bn in 2022. Here’s how the money is really being used—and what it means for green technology builders, investors and policymakers.

Why the $100bn climate finance milestone matters for green tech

$115.9bn of international climate finance flowed from rich countries to developing nations in 2022. On paper, that means the long‑promised $100bn-a-year climate finance goal has finally been met.

Here’s the thing about that number: it’s both a success story and a warning label for anyone building or backing green technology.

If you’re working on clean energy, smart cities or climate adaptation tools, this money shapes your market. It decides which technologies scale, which regions get new infrastructure, and where private investors feel safe following. But the way the target has been met – heavy use of loans, a tilt towards middle‑income countries, and a big role for multilateral development banks (MDBs) – has real consequences for how green technology actually gets deployed.

This post breaks down what’s behind the $100bn milestone, what the data shows about who really benefits, and how founders, investors and policymakers in the green technology space can position themselves for what comes next.

1. The $100bn goal was met – mostly thanks to loans and MDBs

The $100bn goal was finally reached in 2022, two years late, with total climate finance from developed to developing countries at $115.9bn. Half of the single‑year increase came from MDBs, and a big chunk from one country: the US.

What actually drove the jump

Three levers pushed the world over the line:

- Multilateral development banks added about $12.6bn more climate finance in 2022 than the year before.

- US bilateral climate finance – direct country‑to‑country support – more than tripled between 2021 and 2022 under Biden, after years of near‑freeze.

- Private finance “mobilised” by public funding jumped from around $15bn to $22bn.

So yes, the $100bn target was met. But a lot of it depends on:

- Loans rather than grants

- Private investments counted as “mobilised”

- MDB flows attributed back to rich shareholders

Now, with a new pledge to reach at least $300bn a year by 2035, politics has shifted again. Trump’s return to office has effectively wiped out new US bilateral climate aid, while Germany, France and the UK have all cut aid budgets. That means much more pressure on MDBs and private capital to fill the gap.

For green technology companies, this is the real story: if you’re not factoring MDB pipelines and blended‑finance structures into your go‑to‑market strategy, you’re missing where the big public money is actually moving.

2. Who really gets the money – and why that shapes green tech markets

Most of the climate finance doesn’t go to the very poorest countries. It flows to large middle‑income economies such as India, Egypt, the Philippines and Brazil.

Middle‑income giants dominate

Across 2021–2022:

- India received $14.1bn, almost entirely in loans

- China received more than $3bn

- High‑income Gulf states such as the UAE still attracted sizeable climate finance, including over $1.3bn for electricity and waste‑to‑energy projects

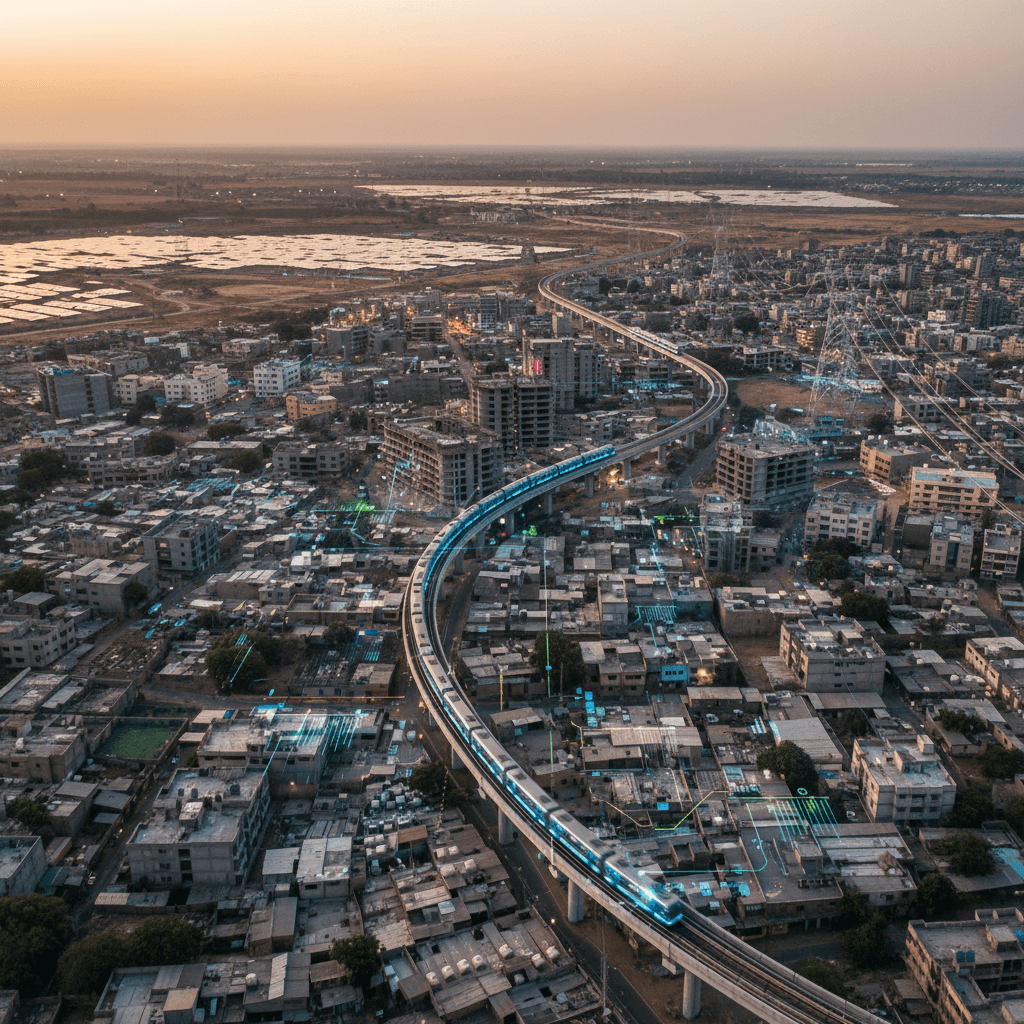

A lot of this money went into big, bankable infrastructure – especially urban rail and metros – rather than smaller, distributed or community‑scale solutions.

Sarah Colenbrander from ODI put it bluntly: middle‑income countries often win because they have the “financial and institutional capacity to design, appraise and deliver large‑scale projects”. In other words: they have plans on the table that banks and donors can actually fund.

What this means for green technology

If you work in clean energy, smart mobility or digital climate tools, this pattern creates both opportunities and blind spots:

- Big-ticket transport and power projects in India, Southeast Asia and Latin America are ideal homes for grid software, optimisation AI, predictive maintenance and smart mobility platforms.

- Upper‑middle‑income markets like China and Brazil can be early adopters of sophisticated green technology because they can absorb large loans and complex financing.

- Least developed countries (LDCs) often get left with smaller, fragmented projects and far fewer resources to experiment with new technology.

Most companies get this wrong. They either chase the hardest markets first (because the need is greatest) or ignore public finance entirely. The smarter approach is usually a two‑track strategy:

- Scale proven solutions in middle‑income markets where MDB‑backed loans and large infrastructure programmes create a pipeline of demand.

- Adapt those solutions for LDCs through grant‑funded pilots and highly concessional finance, often via climate funds or philanthropic partnerships.

3. Japan’s rail strategy: a case study in tied finance and green infrastructure

One detail from the data is frankly wild: around 11% of all bilateral climate finance globally in 2021–2022 was Japanese money for rail and metro systems in India, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

Japan is the single largest climate‑finance donor in that period, responsible for about a fifth of bilateral and multilateral flows. Of the top 20 bilateral projects, 13 were Japanese, and $7.6bn of that went into rail.

The catch: loans and “tied” aid

There’s a pattern behind this generosity:

- More than 80% of Japan’s climate finance is loans, not grants.

- Nearly a fifth of those loans are non‑concessional – essentially market‑rate.

- Many of the projects are tied to Japanese firms and workers.

Yuri Onodera from Friends of the Earth Japan calls this a “moral hazard”: using climate finance as a vehicle to expand domestic corporate interests, while counting the full loan amount as climate support.

The lesson for green technology businesses

You might not like this model, but it’s highly relevant:

- Large donors often want technology, jobs and contracts flowing back home.

- If you’re a green tech company in a donor country, partnering with your own export agencies, development banks and aid institutions can be a very practical route into emerging markets.

- If you’re based in a recipient country, you’ll need to be realistic: many “climate” projects are built around the donor’s industrial strategy. That means winning as a local subcontractor, integrator or O&M provider can be more feasible than leading the EPC contract.

There’s a better way to approach this, though: structure deals so that local capacity-building, data ownership and technology transfer are baked into the project from day one. Many MDBs and climate funds are increasingly sensitive to this and will back projects that prove real domestic value.

4. Africa, clean power and the role of AI-driven green technology

Around 730 million people still live without electricity access, and roughly 80% of them are in sub‑Saharan Africa. Climate finance has started to move the needle, but far from fast enough.

Between 2021 and 2022, donors funded 500+ clean-power and transmission projects in African countries without universal access, worth about $7.6bn.

What’s being funded

Projects include:

- Chad’s first grid‑connected solar power plant

- New hydropower in Mozambique

- Grid expansion in Nigeria

Almost all of this sits in traditional project categories: generation assets, high‑voltage lines, substations.

Where green technology can 10x the impact

This is where AI and digital green technology come in. The physical assets are only half the story; the other half is how you operate them.

There’s huge room – and growing appetite from MDBs and donors – for:

- AI-based grid optimisation to cut losses and manage variable renewables

- Demand forecasting to size systems correctly and reduce curtailment

- Remote monitoring using IoT and machine learning to lower O&M costs

- Pay‑as‑you‑go and mini‑grid management platforms to expand access affordably

Because many of these countries are starting from relatively low penetration of legacy tech, they can leapfrog straight to smart infrastructure – if solutions are:

- Robust in low-connectivity environments

- Localised for regulatory and payment realities

- Priced to work with concessional and blended finance, not just VC‑style returns

From what I’ve seen, the most successful players treat MDBs and climate funds almost like anchor customers: they co‑design projects with utilities and governments, then structure the financing so tech costs are embedded in the overall capex, not bolted on as an afterthought.

5. The debt trap problem: when climate finance is mostly loans

One of the most troubling findings from the data is how much least developed countries rely on loans for climate projects.

Across the 44 LDCs, developed nations pledged $33.4bn in 2021–2022. More than half ($17.2bn) came as loans. At the same time, analysis from IIED shows these countries spend twice as much servicing existing debts as they receive in climate finance.

Countries such as Angola are emblematic: over the two years, almost all its climate finance came as loans, including more than $200m from France and over $570m from multilaterals to support water infrastructure and related projects.

For green technology companies, this matters for a simple reason: debt‑strained clients are highly risk‑averse.

How to design green tech projects that don’t make debt worse

If you’re working in or with LDCs, you’ll hit one of these three walls:

- Governments can’t take on more sovereign debt.

- Utilities are already financially distressed.

- Private customers can’t handle high capex.

The solutions that tend to work are:

- Service-based models (e.g. “energy‑as‑a‑service”, “cooling‑as‑a‑service”) where donors or blended‑finance vehicles fund the assets, and users pay for outcomes.

- Results‑based finance where payouts are linked to verified emissions cuts or energy access improvements, often measured using digital MRV tools.

- Highly concessional blended structures, where grants absorb early risk, and cheaper loans come in only once performance is proven.

From a policy standpoint, I’d argue a lot more of the $300bn goal should be grant‑based for adaptation and for digital infrastructure, precisely because those returns are social and system‑wide, not easily captured by a single borrower.

6. Adaptation finance: still the poor cousin, but shifting for vulnerable states

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries committed to move towards a balance between mitigation and adaptation in their climate finance.

We’re not there. Across 2021–2022:

- Around 58% of climate finance targeted mitigation (mostly energy and transport)

- About 33% supported adaptation

- The rest was labelled “cross‑cutting”

Yet for the most climate‑vulnerable countries – small islands, drought‑prone African nations, low‑lying states – a majority of their funding is now adaptation‑focused.

Projects include:

- Climate‑resilient, productive agriculture in Niger

- Disaster resilience and relocation support in Micronesia

- Programmes supporting people displaced by climate impacts in Somalia

Where green technology fits into adaptation

Adaptation has been seen as “hard to finance” because returns are indirect. That’s changing fast as digital tools make risk and impact more measurable.

There’s growing space for:

- Climate risk analytics and early‑warning systems

- Precision agriculture tools for smallholders, using remote sensing and AI

- Resilience dashboards for cities and infrastructure operators

If you’re in the green technology space, this is an under‑served market. Donors and MDBs know adaptation finance lags, and they’re under pressure to fix it. Arriving with:

- A clear theory of change (how your tech reduces risk or loss)

- A credible measurement framework

- Partnership offers for local institutions

…puts you ahead of a lot of the competition.

Where green technology builders go from here

The $100bn climate finance story isn’t just about whether rich countries kept a promise. It’s a map of where green technology will scale first, and on what terms.

A few practical conclusions:

- Follow the MDBs and climate funds. Their pipelines define near‑term demand for clean energy, smart cities and adaptation tools.

- Design for middle‑income markets, adapt for LDCs. Use loan‑backed megaprojects to prove and scale your technology, then work with grant and blended finance partners to reach more fragile markets.

- Bake in local value. Tied aid and donor‑centric projects aren’t going away, but projects that visibly build local skills, jobs and ownership are easier to fund and harder to criticise.

- Treat adaptation as a growth market, not a side project. Vulnerable states are already steering more of their climate finance towards resilience. They need tech that turns data into real‑world decisions.

As climate finance ramps towards the new $300bn goal – and as private investors are pushed to match public ambition – the companies that understand how this money actually flows will have a serious advantage.

If you’re building or funding green technology, the question isn’t whether climate finance is big enough. It’s whether you’re positioned where the next wave of public and blended capital will hit.